Putting More Debate in the Presidential Debates

Last week, Republican consigliere and frequent electoral debate negotiator Ben Ginsburg appeared on Bloomberg News’ “With All Due Respect,” with John Heilemann and Mark Halperin, to discuss the effort that he led to take debate negotiations with the networks out of the hands of the Republican National Committee. Several candidates were unhappy, as everyone knows by now, about the moderators’ performance during the CNBC Republican Presidential Debate on October 28th. The conversation on WADR turned to the Annenberg Debate Reform Working Group, of which Mr. Ginsburg is a member.

Formed by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, and its highly esteemed director Kathleen Hall Jamieson, the Working Group put out a set of 50-page report over the summer with recommendations designed to close the gap between the presidential debates’ civic promise and their increasingly spectacle-ized and infotainment-centered condition.

Asked by Heilemann/Halperin how likely it was that the Working Group’s recommendations will be adopted going forward, there was more of a hint of wry dismissal in Ginsburg’s voice: “They contain a lot of good ideas, and I guess we hope that those good ideas will get a serious review this election cycle.” It would be a shame if those words expressed little more than a hollow hope; the Annenberg recommendations contain, like the seed in an acorn, the source of the debatification of the presidential debates, beneath a carapace of reforms of perhaps dubious viability.

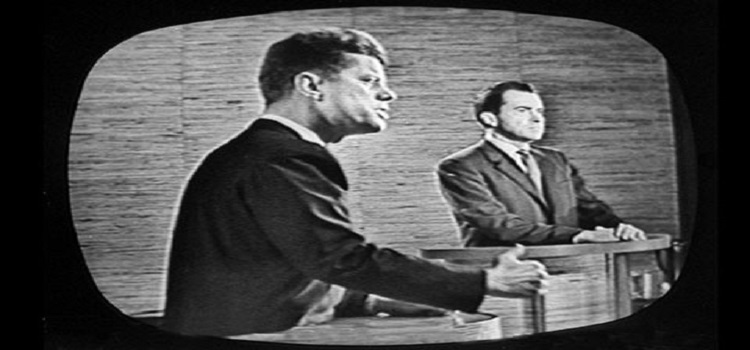

Concerns about the quotient of actual debating in the presidential debates go back nearly to their beginning. And their beginning was of course contemporaneous with the origin of modern techno-visual media culture. The gold standard of electoral debates occurred in Illinois in 1856 between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas who engaged in a seven-event series, with each debate lasting more than 3 hours and featuring no moderator. But Lincoln and Douglas were senatorial not presidential debates, and their rhetorical performance was – if not nonpareil – likely intimidating and exceptional. There were presidential debates in the 1940s and 1950s, but only in advance of the primaries; both parties declined to debate prior to the general election in those decades. Then on September 26, 1960 John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon faced off for the first time in what sounds to today’s ears a genteel, respectful exchange, though one that circled back frequently to differences in policy and position between the candidates. Among other formatting components of the original presidential debate template, Kennedy v. Nixon contained extensive argumentative clash– it seemed intuitively, as what debate itself meant to both men.

Sixteen years went by until the next presidential debates, between Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter in October, 1976. In the interim, criticism of the 1960 debates arose as social science research[1] identified a sharp discrepancy between polled reaction to the debate from those who watched it on TV and those who listened to it on the radio. Kennedy seemed to be a substantial beneficiary of his more youthful, comely, and becalmed visage, relative to Nixon’s sweaty, gaunt, and bestubbled one. The tele-political age had arrived.

Presidential debates every four years from 1976 – 2012 were more or less widely watched — ranging from nearly 50% of all adult Americans viewing at least one in 1980 to 28% doing so in 2012, though the difference in the absolute number of viewers between those two years was considerably smaller – and widely criticized. The Twentieth Century Fund, for example, put together in 1986 a panel of political Brahmin led by Newton Minnow. This earlier working group of insiders produced 10 recommendations to improve the presidential debates, which in a variety of ways it found wanting.

More recently the volume of criticism of the presidential debates has risen, and this fall a partisan cast to the critique has become more pronounced, as the Republican National Commission was “outraged” [2]after the third debate in Boulder, Colorado, on October 28th, for the “bias,” “gotcha questioning,” and “unprofessionalism” of the CNBC moderators. St. John’s College President Christopher Nelson spoke for many critics of presidential debates when he decried the “flow of vapidity” emanating from both the candidates and the moderators.[3]

An RNC spokesman accused the networks of wanting to stage “an Ali-Frazier prizefight” instead of a dignified presentation of candidates’ ideas for public policy and the future of our country. But conflating sensationalism and a fostering of a sharp clash of ideas is a considerable misjudgment. And this circles us back to the Annenberg Debate Reform Working Group and its transformational seed of an idea for improving the civic value of these debates. The presidential debates need more, not less, clash between the candidates. They don’t need insults or ad hominems – no more, “He’s a loser” or “His poll numbers tanked, that’s why he’s on the end” or “Even in New Jersey what you’re doing is rude” or “Is this a cartoon version of a candidacy?” But the candidates need to engage with each other, they need to respond to each other, they need to refute each other’s claims, critique each other’s reasoning, evaluate each other’s evidence, attack each other’s positions. In short, they need to debate. What the presidential debates desperately need is more debating, and debating is at its essence a rule-bound, reasoned, evidenced, and intense clash of ideas.

At its core, the Annenberg Working Group Report makes this point very clearly. One has to wade through some formatting, site regulation, and audience-appeal ideas, but the heart of the report is about getting the candidates to engage with each other’s positions and arguments. The Working Group rightly calls into question how little change and evolution has occurred in the presidential debate format in 50+ years and states that “the candidates themselves should be responsible – and therefore accountable – for the quality of their performance. With a candidate-centric format, success or failure rests on the individual candidates’ shoulders.” This was reasoning unarticulated by Chris Christie but that warranted his calling out fellow candidates after the Boulder debate for their whining about the rules, and behind Barack Obama’s recent criticism of the GOP for complaining about the CNBC moderators.

In a debate, the debaters themselves have the burden to critique and refute the positions and arguments advanced by their competitors. It is not the burden of the moderators to undertake that refutation and argumentation for the candidates – though the candidates would of course prefer that someone else do that heavy lifting for them. It is this role refinement that the Annenberg Working Group calls for by suggesting that moderators should stay in the referee lane, and stay out of the “probing or investigative journalist” lane. The Working Group rightly says that there is a fundamental distinction and in fact opposition between the two roles, and what a debate needs is an order-keeping official, not a gadfly or adversary to each of the participants.

The Working Group – like the Twentieth Century Fund and other debate commissions and review boards – have called for more argumentative clash between the candidates, replacing what in too many cases have functioned as joint news conferences. Our democracy sorely needs presidential debates (and it is revealing that very few people have called for their abolishment, despite an on-going din of controversy and critique). We just need the candidates to actually debate each other.

Footnotes

[1] David Zarefsky, “Spectator Politics and the Revival of Public Argument, “Communication Monographs 59, no. 4 (1992): 412.

[2] http://www.politico.com/story/2015/10/rnc-drops-nbc-partnership-215388

[3] http://www.forbes.com/sites/christophernelson/2015/09/18/bring-serious-questions-back-to-presidential-debates/