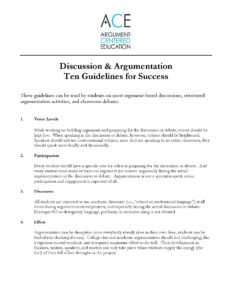

Ten Guidelines for Successful Participation in Argument-Based Discussion or Debate

These guidelines can be used by students to ensure their successful participation in argument-based discussions, structured argumentation activities, and classroom debates.

Voice Levels

While working on building arguments and preparing for the discussion or debate, voices should be kept low. When speaking in the discussion or debate, however, volume should be heightened. Speakers should not use conversational volume; since they are speaking to an entire classroom, they should speak more loudly and dynamically.

Participation

Every student should have a specific role (or roles) in preparing for the discussion or debate. And every student must make at least one argument (or counter-argument) during the actual implementation of the discussion or debate. Argumentation is not a spectator-sport: active participation and engagement is expected of all.

Discourse

All students are expected to use academic discourse (i.e., “school or professional language”) at all times during argument-centered projects, and especially during the actual discussion or debate. Disrespectful or derogatory language, profanity, is excessive slang is not allowed.

Effort

Argumentation can be deceptive: since everybody already does in their own lives, students can be fooled into thinking it’s easy. College-directed academic argumentation should feel challenging, like a vigorous mental workout, and it requires maximum effort to do well. Their development as thinkers, writers, speakers, and readers can only take place when students supply the energy (the fuel) of their full effort throughout the project.

Focus

Staying focused ensures that work time and effort are used efficiently and are converted into learning and accomplishment. No one can stay focused 100% of their time, but students should keep the percentage of time they spend on task and on argumentation as close to that goal as they can, always trying to improve their performance in this area.

Preparation

One rule that has very few if any exceptions is the rule of preparation: debates and argument-based discussions are never any better than the preparation that students undertake to get ready for them. Winging it can sometimes work in informal discussions, and certainly is the norm in our daily conversations. But because argumentation requires carefully developed evidence and reasoning, and because refutation demands critical thinking to expose flaws or weaknesses in another point of view, the quality of preparation is highly correlated with the quality of debate and discussion.

Evidence

One of the twin pillars of academic argument, the standard of evidence should prompt students to always ask themselves – and be prepared to be asked by other students or the teacher – what is the evidence for my point, and how credible, authoritative, and sufficient is that evidence? They should also accept that they have the responsibility of analyzing their own evidence to demonstrate how it proves their point (reasoning, in the language of argument). And they should think critically about other sides’ or students’ evidence, and be prepared to closely analyze that evidence.

Refutation

The other twin pillar of academic argument, the standard of refutation requires that in a debate all arguments made by another side be responded to and refuted. Refutation is defined broadly as any answer or response to another point that convincingly shows that that point does not undermine one’s position. Strategic concessions are allowed and sometimes strongly recommended. An argument that is not responded to in an academic context is tacitly agreed to. This standard drives the locus of critical thinking in academic argumentation.

Note-Taking

During the structured argumentation activity or debate, all students are expected to “flow” – debate jargon for formal note-taking. Flowing enforces refutation, the locus of critical thinking in argumentation and debate, by recording the arguments made, and providing an objective artifact of those that have been responded to and those that have not been, and how arguments are developed during the course of a debate.

Higher Purpose

Academic argumentation and debates are not about winning, they’re about learning, growing in knowledge and thinking skills. In the process of driving their own arguments and overall position, students are learning more deeply about the issue, and the arguments on all sides of it, in addition to being better equipped to think critically about it and other issues. Students should come out of structured argumentation activities, discussions, and debates ready to take a fresh, better-evidenced, more strongly reasoned, and independent position on the issue.

A downloadable version of these ten widely usable, and rigorous but encouraging guidelines is available here: