The Atomic Bombing of Japan, Document-Based Debates, and Close Evaluation of a Flow Sheet Model

This is a comprehensive argument-centered mini-unit on the United States’ decision to use atomic bombs against Japan at the end of World War II. Students study this momentous decision and its consequences through videos, primary documents, and analytical essays. They use these sources to formulate and build out arguments on the fundamental and enduring debatable question:

Was the United States justified in using atomic bombs against Japan in World War II?

Simultaneous table debates take place on this issue across the classroom. These debates are followed up with a focus on the academic means and methods that are used to evaluate competing arguments on a complex, rooted, significant controversy such as the historical question that envelopes America’s use of atomic weapons in WWII. Students conduct one-on-one argument evaluation, using a model debate flow sheet. Then they conclude the mini-unit by evaluating the argumentation in a fully modeled debate and its tracking form.

Overview

Perhaps the most momentous decision in 20th century American foreign policy was the decision President Harry S. Truman made in August, 1945, to use atomic weapons against Japan close to the very end of World War II.

The Manhattan Project had won the race to build the world’s first nuclear weapon, a race rivetingly recounted in Steve Sheinkin’s Bomb. In the summer of 1945, the allies had vanquished Germany and the Third Reich, and with American weariness over the lingering fight with the tenacious Japanese military, President Truman was faced with the decision over whether to use the product of the successful scientific quest to create a bomb that harnessed the energy released when the atom was split and fused.

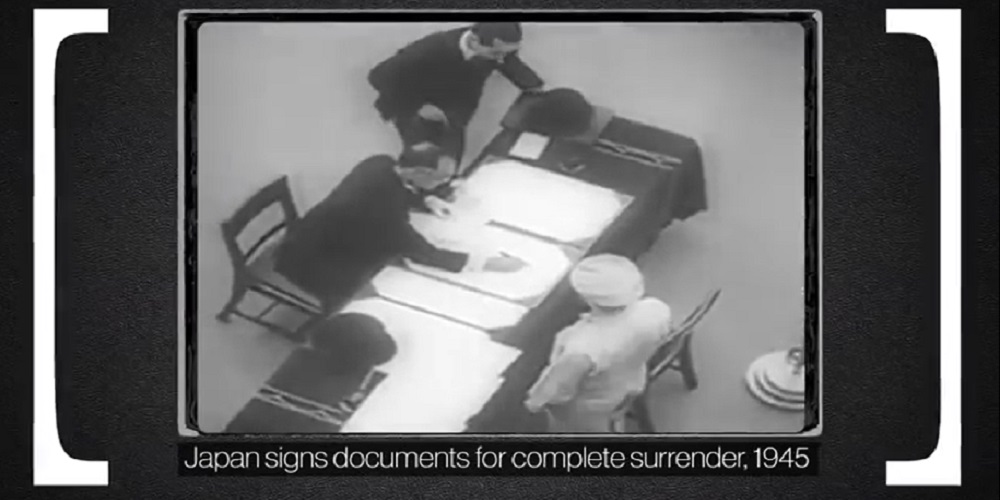

When the American military bomber the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the world forever changed. The nuclear age had been opened, along with its catastrophic power and deathly immanence. A second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9th. Five days later Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies and the United States. The Second World War had ended — a potential blood-bath attendant to an American land invasion of Japan had been averted. But the fundamental question about the wisdom of using a categorically more powerful and lethal weapon, on the civilian population of America’s enemy, had only begun.

Sources

Students should be given copies of the Media List, and they should begin to research the issue by reading essays from the Background/Both Sides section of the list.

Students should then be paired into two-person teams. Pairing can be done randomly, heterogeneously to achieve peer leading and teaching, or by ensuring (through the year) that students have a chance to work with every other student in the class. Teams should either select a side on the debatable issue (using a Side Preference Form from Argument-Centered Education) or they should be assigned a side. You will need to ensure that you have an even number of teams on each side of the issue.

Next students should view the videos from the Media List, using a Video Annotator from Argument-Centered Education to begin to gather evidence that they ultimately be able to use in their argumentation.

This is the 2017 BBC video that uses testimony from Japanese survivors of the atomic blasts in WWII to provide some sense of the experience:

This is a short video from the Discovery Channel on the factors that led the U.S. and specifically President Harry Truman to decide to drop atomic bombs on Japan in August, 1945, in hopes of ending World War II:

This is the video from British educational video company The Top Fives which provides its own historical summary of the run-up to the dropping of the atomic bomb, with an emphasis on the impact of the bombs on the Japanese victims:

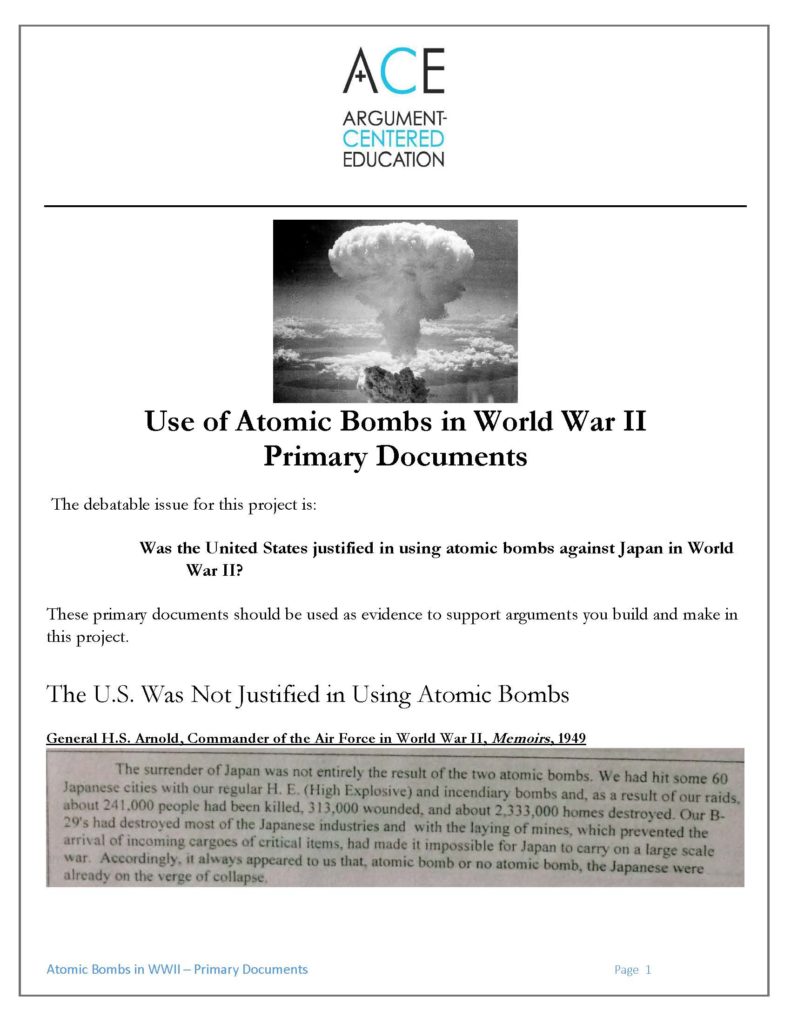

Teams should then be given this small set of primary documents. Each team should be told that it is required to use two primary documents in its arguments and one primary document in its counter-arguments, as they are building arguments in preparation for their table debates.

Table Debates

Teams should assemble their evidence gathered through their study and research on the debatable issue. They should formulate the argumentative claims that they may want to build, and choose the three for which they believe they have the strongest evidence to support. They should also list out the arguments which they want to build counter-arguments against.

Teams should be given Argument-Centered Education Argument Builders and Counter-Argument Builders in preparation for their debates. You should then work through the Table Debates Activity, culminating in one or more simultaneous table debates throughout the classroom on this debatable issue.

Argument Evaluation

This is the simple sequence of instructional steps for the Close Evaluation of Arguments Activity. This Close Evaluation of Arguments Activity will take 2 – 3 class periods.

(1)

Pair students up. You can use the pairings that you were made for the Table Debates (for expedience or because these teams work especially well together), or you can re-pair students to have students working with different partners.

(2)

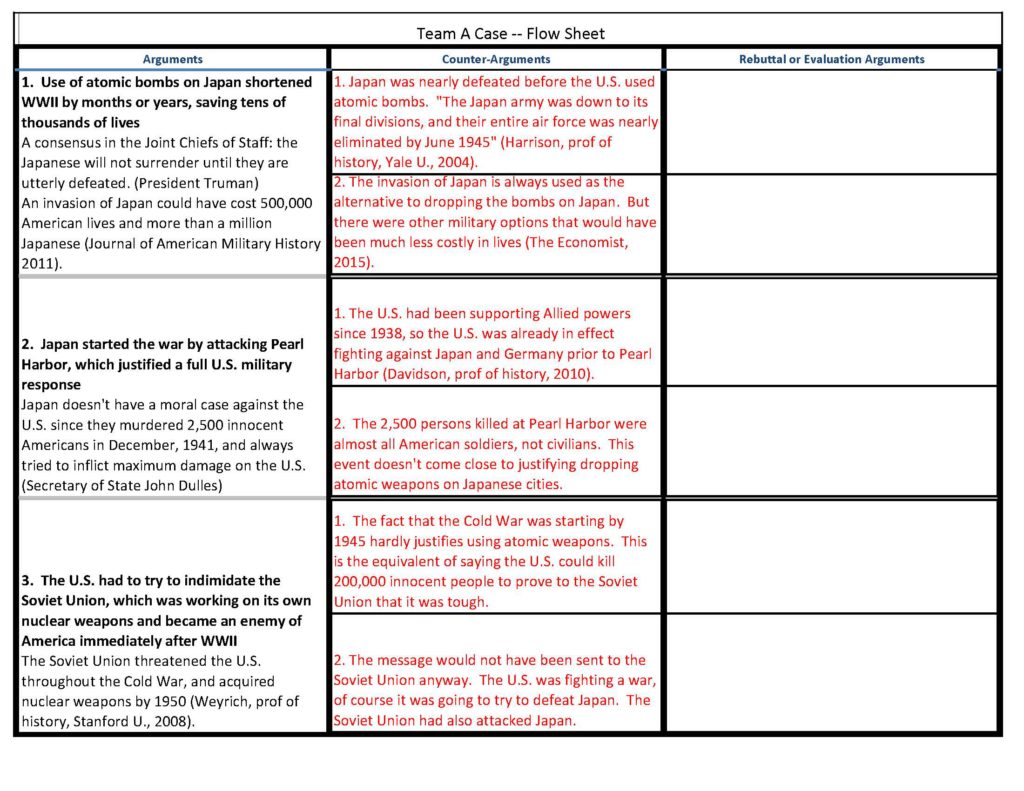

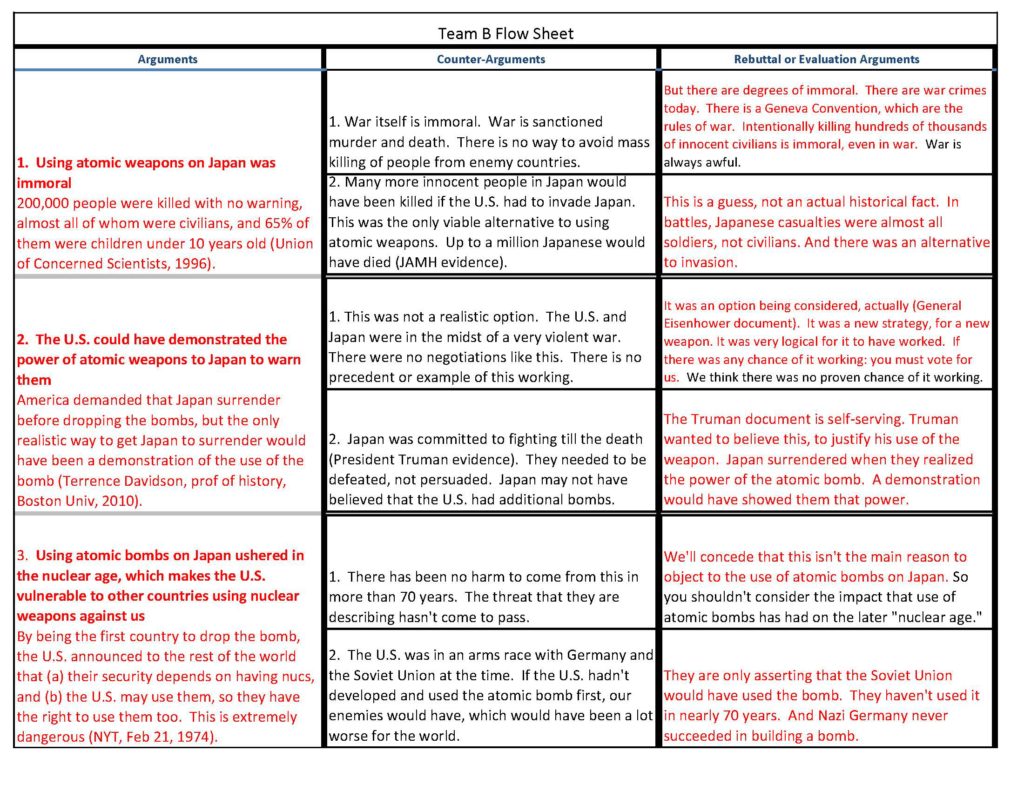

Distribute the Flow Sheet Model (Through Counter-Arguments), one copy of each sheet for each student (so two sheets per student). Review with the full class the arguments and counter-arguments on this Flow Sheet Model.

(3)

Tell the students to pick sides (Team A, arguing that use of atomic bombs against Japan was justified, or Team B, arguing that the use of atomic bombs against Japan was not justified). Give students about 15-20 minutes to complete their evaluation arguments. Note that each student will want to respond to (“rebut”) the counter-arguments made against their side’s arguments. They will also want to be prepared to compare their arguments to the other side’s arguments. Team A – since it gives their Closing Statement second – can add arguments to respond to the Team B evaluation arguments on the Team B flow sheet after the Team B speaks.

(4)

After students have been given time to complete their evaluation arguments, begin the sequence of having students deliver their Closing Statements, at their tables, against their partner. These Closing Statements will be delivered simultaneously, as in the Table Debates format. Give Team B 3 minutes to give their Closing Statement. Then give Team A 3 minutes to give their Closing Statement.

(5)

After these Closing Statements, consider either (a) sharing out, asking pairs to share with the class the best evaluation arguments in their debate, or (b) showcasing the most advanced pair of Closing Statements in front of the full class, ending with an analysis of this pairs particular strengths. Collect the completed Flow Sheets from each student, too.

(6)

Next day, have students continue to work in their pairs. Distribute copies of the Full Flow Sheet Model (two sheets) to each student, and distribute one copy of the Argument Evaluation Questions per pair.

(7)

Circulate, monitor, and support while students in pairs discuss and evaluate argumentation. Be sure that one of the students in each pair has been tasked with writing out the responses to the questions, noting where the students in the pair do not come to an agreement in their response.

(8)

After the students have had about 30 minutes to discuss and write out their responses to the questions on argument evaluation, pair the pairs of students (into groups of four) and have these pairs read their responses to each other to certain questions that you select and announce. After they read their responses to each other, they should discuss their differences (where they exist), suggesting that they argue through these differences, possibly ending with one or both sides revising their written responses.

(9)

If there is time (of if you want to take the additional time), conduct a sharing-out discussion with the full class, highlighting the sites of differences between the matched-up two pairs and how those differences were resolved.

(10)

Collect and assess the written responses to the Argument Evaluation Questions.