Introducing the Observation of Argument-Centered Instructional Capacity Inventory, Part 2

This is Part 2 of my introduction of the Observation of Argument-Centered Instructional Capacity Inventory, an instrument that helps teachers and administrators know what proficient and masterful incorporation of argumentation and critical thinking throughout curriculum, instruction, and classroom culture specifically looks and sounds like. This allow teachers to take stock of what they are doing well already, and where they want to grow as professionals. And it enables administrators to monitor and support the process of professional capacity building, toward a school that provides authentic college preparation for every student.

Part 1 of this introduction can be found here. Part 2 will pick up with a close examination of the eight items in each of the domains after Curriculum – namely, Instruction and Culture. Then we will discuss the utility of the Form used to tabulate and collect ratings and comments, which formalizes the inventory (whether it is self-performed or not) of current professional capacities.

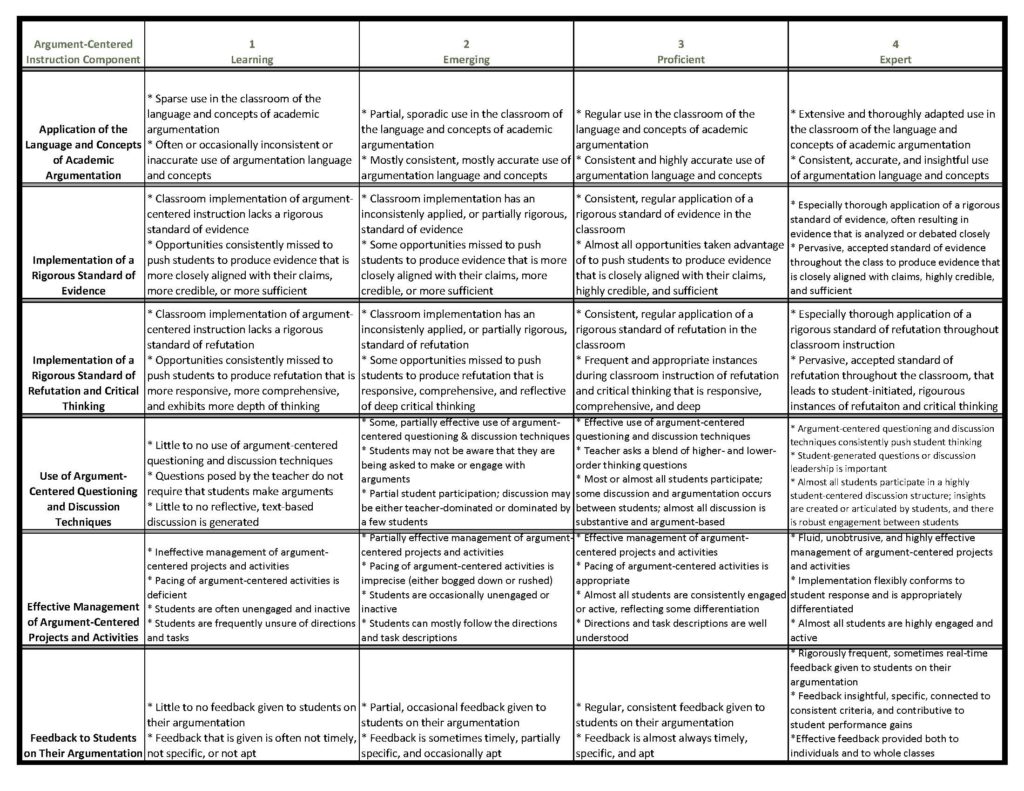

Instruction

Instruction of course is the in-class implementation, enactment, and in some instances adaptation of curriculum. The language and concepts of academic argument are important enough that they are itemized as a capacity in both Curriculum (preparation) and Instruction (implementation). The capacity is parallel: teachers should use this language and these concepts consistently, extensively, appropriately, and accurately.

As the foundation of argument-centered instruction is made up of the standards of evidence and of refutation, these two standards play a very important part in the capacity to use this pedagogy effectively. Teachers should apply rigorous standards of evidence and of refutation consistently, regularly, and thoroughly. A standard of evidence that is rigorous is one that pushes students not only to use evidence to support their claims, but to analyze the strength of evidence, based on clear and consistent criteria, which to us are alignment, credibility, sufficiency, and reasoning. Similarly, the refutation standard should mean not only that opportunities for the critical thinking applied to others’ views are created and taken advantage frequently and consistently, but also that refutation should be pushed to demonstrate criteria such as responsiveness and depth of thought.

Questioning and discussion techniques are as essential to argument-centered instruction as to any pedagogy. Teachers should seek to appropriately and flexibly blend questions requiring higher-order and lower-order thinking. This item descriptor can be translated to any analytical system for levels of thinking in use at the school – for example, in Webb’s Depth of Knowledge framework, questions should be blended over all four levels of thinking. Discussion should include argumentation, ideally between students at times. Questions, and even argument-based discussion itself, should be generated by students, too.

Management of argument-centered activities, projects, and formats is its own particular professional skill, and an important one. Effective management is fluid and unobtrusive, maximizing instructional time in the classroom. Pacing is an important part of good management, so that each part of an activity or project is given its proper and proportionate time. Management should strive to achieve full engagement of students, differentiating as necessary, and responding to classroom exigencies and occurrences flexibly and with instructional focus.

Finally, feedback to students is a crucial component of effective argument-centered instruction. Teachers should strive to provide real-time feedback to students on their argumentation, and feedback that is insightful, clear, and related to objectives. Feedback should be provided to individuals, groups, and full classrooms, depending on the assessment or assignment.

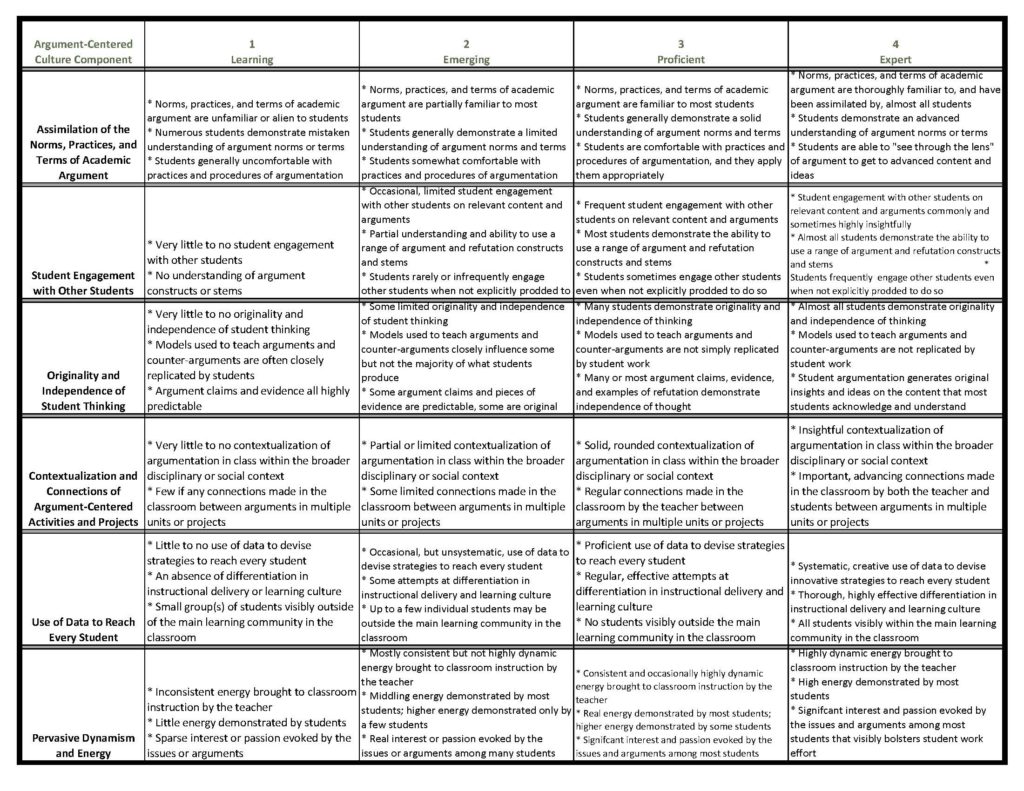

Culture

This is the one of the three primary domains of argument-centered instructional professional capacity that organizes the skills required to create, establish, and maintain and argument-centered classroom culture.

The parallel of “language and concepts” in the Culture domain is that students have assimilated the norms, practices, and terms of academic argument. They demonstrate this through their comfortable, fluid, spontaneous use and application of these norms, practices, and terms. Students are comfortable with them, and they are correct most or all of the time in doing so. Ultimately, students are able to see through the lens of argumentation in order to have deeper, richer, better informed, more critical ideas and conversations about course content.

In a fully developed argument-centered classroom culture, students engage with each other frequently over relevant content and arguments. They demonstrate an understanding of the constructs and stems of argumentation, including refutation. Sometimes their engagement with each other is prompted by the teacher and sometimes it is spontaneous, indicating how thorough the culture of engagement with other views has been assimilated.

An argument-centered classroom culture also facilitates and produces original and independent student thinking on course content. This is an often overlooked indicator of the quality of instruction in a classroom. As students think critically about course content as a matter of routine, a matter of intellectual habit, they will be led to think beyond the arguments and ideas that others have written and spoken, and they will think for themselves, what they themselves believe is true and most defensible, and they formulate their own views and arguments to support them.

Another indicator of an advanced, fully developed academic culture in an argument-centered classroom is the inter-connection of information and ideas across units, and the contextualization of classroom learning within a broader social and intellectual context. Students are thinking deeply about course content when they are making these cross-applications and connections with other learning that they have been doing. And they are emerging from a classroom with a heightened sense of the larger meaning of their learning when they are putting it in the context of their world outside the classroom. The advanced skill interlaid into a teacher’s work to achieve a classroom culture that produces these connections and contextualizations is eliciting them without heavy prompting or prescriptive direction. When they are coming from students with minimal and light cueing up, they are reflective of the kind of classroom culture most productive of college readiness.

The use of data is a crucial professional technique to achieve meaningful and measurable learning growth for every student. The teacher’s use of data can be considered part of a classroom’s academic culture when it is regular, consistent, and systematic, with the observable intention of differentiating instruction and achieving measurable academic growth for all students in the classroom. The effect of employing data this way should be the full inclusion of every student in the classroom community.

A final crucial indicator of a highly developed academic culture in an argument-centered classroom is a pervasive dynamism and energy. The energy in a classroom comes from the teacher first, as with almost everything else in the classroom, comes first from the teacher. This does not mean that the teacher has to be physically demonstrative, performing at the center, as though on a stage. To the contrary, this can often be a means of replacing student energy with a kind of kineticism from the front. Some teachers are highly active, and that can work. What’s important, though, is that the teacher projects an acute, serious attentiveness throughout instruction. Student energy typically mirrors and often augments teacher energy. When students exert observable, consistent energy on the academic work in the classroom, a mutually reinforcing dynamism is evident, and everything else going on in instruction is powered.

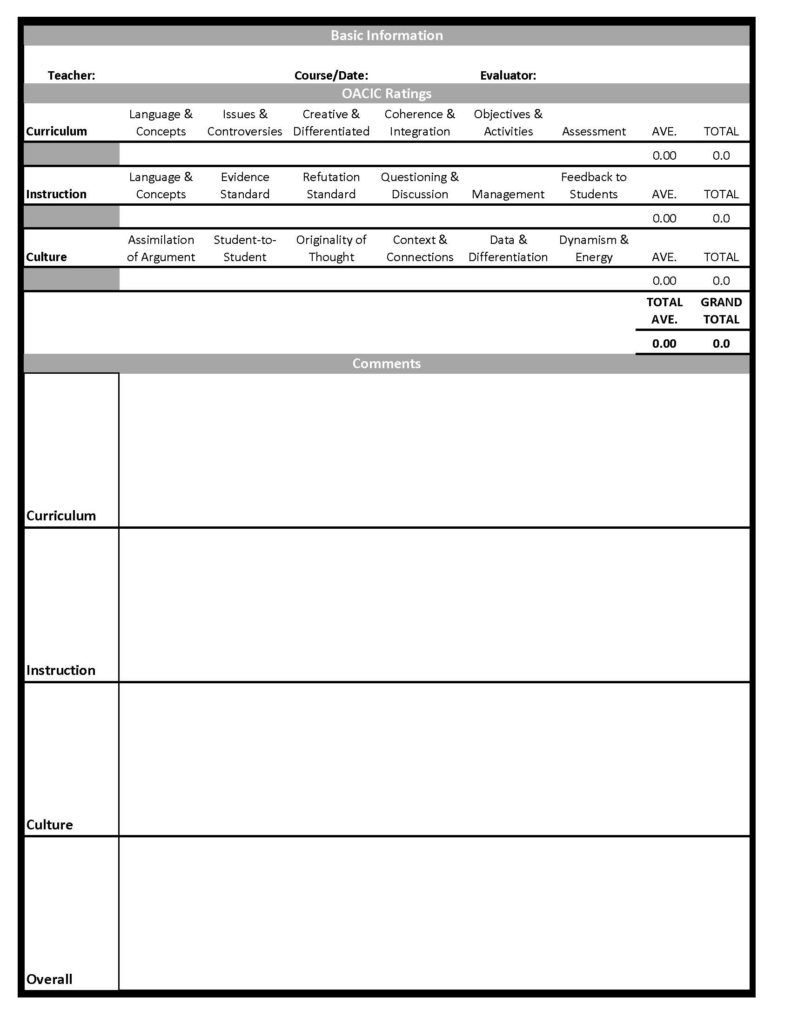

Inventory Form

The Inventory Form tabulates and collects the inventory ratings and comments, putting them together in one place and recording them for later and even continual reference. The domain pages can be (and often are) also used to register ratings, by circling or highlighting the rating number for each of the eight entries in each domain, but then they are entered into the Form, which if the Excel document is being used they are auto-tabbed and averaged, for ease of quantitative analysis. Note that it has also become common practice to use ½ points, to provide some additional granularity to the four-point scale.

At the top of the Form the teacher, course, and date of completion of the Inventory are included. The name, too, of the individual who is doing the Inventory is quite intentional: inventorian, rather than evaluator or even rater. The bottom half of the Form includes space for comments to explicate the most salient points in the professional capacity inventory within each of the three domains, and how they all fit together for the teacher.

In a future post I will discuss a set of guidelines that we have developed for the best use of the Observation of Argument-Centered Instructional Capacity (OACIC) Inventory can be used to greatest effect, as well as a few of the pitfalls to avoid. For now, I would encourage all teachers and administrators interested in argument-centered instruction – and in understanding what it is exactly that makes a teacher a proficient practitioner of it – to review the OACIC Inventory closely and to contact us if they have questions or they are interested in learning more.