Is Soccer the Best Sport in the World? (Part 1)

I’d like to start this post by declaring that I am not myself a fan of the sport that America calls soccer and the rest of the world calls football. But after I listened and made a minor contribution to a friendly dispute at a family function about the merits of soccer in comparison to other sports more popular in this country, I recognized that this issue could be useful in my work with teachers, building their professional capacity to teach their students to think critically and make college-directed arguments on the key questions in their curriculum content. A debatable question that I have been using often of late with partner teachers is:

Is soccer the best sport in the world?

This debatable issue is obviously arguable; it is clearly not a closed question. Some people might think it is too open, that it is simply subjective. But academic argument takes place all the time on questions that the writer or speaker tries to make a case can be addressed rationally with evidence and reasoning. Evidence-based argument often in effect attempts to covert a matter that is considered subjective into something more objective. Was the United States justified in using atomic weapons on Japan in World War II? This isn’t a closed question, and its solution will never look like a math problem. But those who argue that the U.S. was justified cite fact-based evidence that an invasion of Japan would have cost far more lives (both American and Japanese) than were lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945. These advocates invoke a utilitarian principle that the most ethical decision in a case like this is the one that saves the greatest number of lives. On the other side, historians reference documents to show that the Japanese were close to surrender and would have been persuadable through methods short of invasion or atomic decimation. They often cite moral principles that the U.S. has long stood behind to protect innocents even in wartime. The point here is that argumentation is inherently the process of bringing facts and reasoning together to make the case that one position on an open question is more valid, more defensible, than the alternatives.

On the soccer issue, partner teachers have been working on calibrating what a good argument looks like, built around a given piece of evidence, supporting different positions on the issue. After we converge on our argument and counter-argument models, we discuss teaching strategies to lead their students closer to exemplary argument and counter-argument construction of their own.

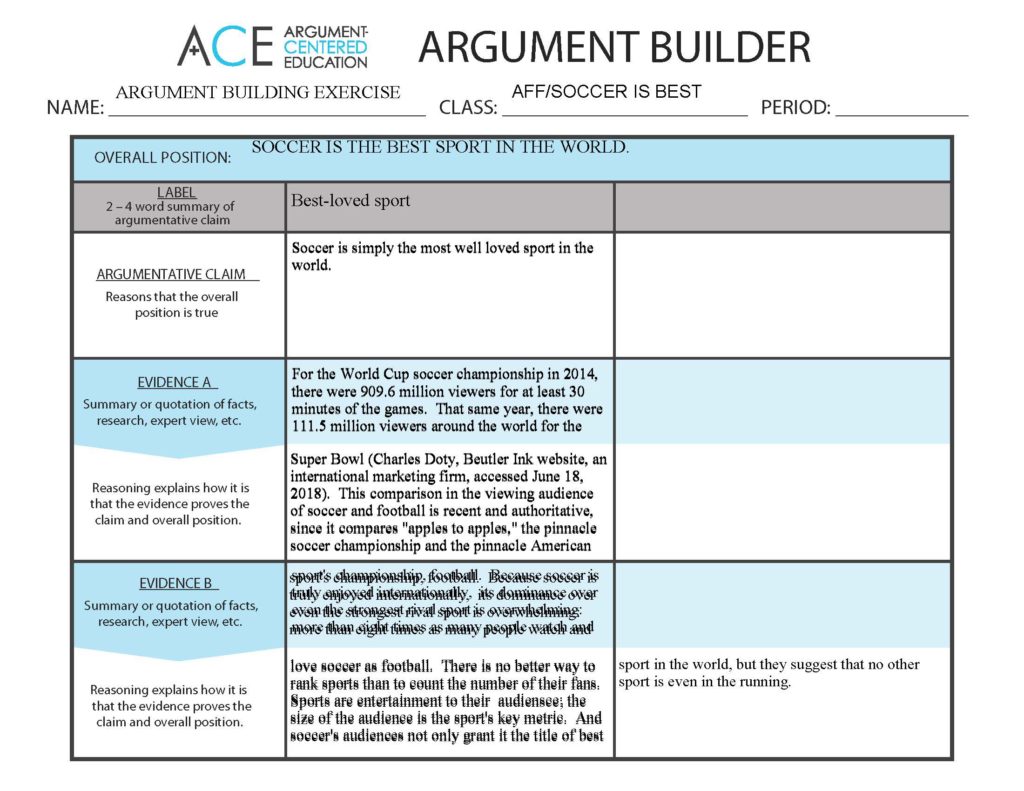

Argument Building Exercise

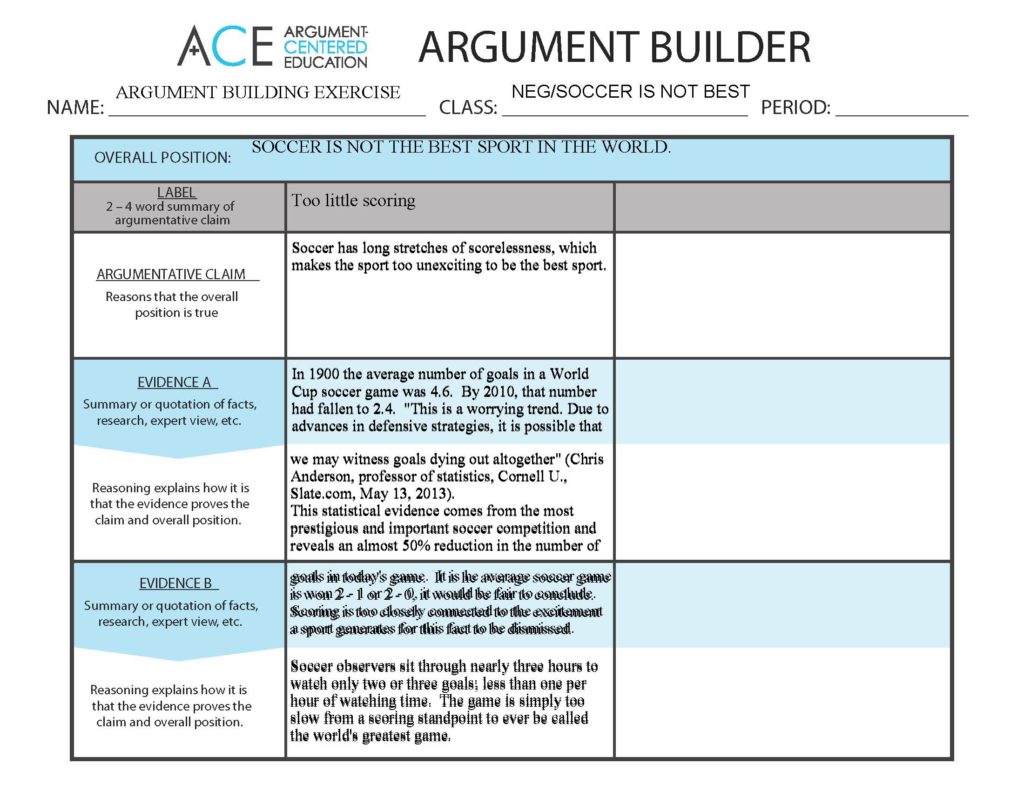

This professional development exercise begins with the evidence teachers are given to build two arguments, on supporting the position that soccer is indeed the best sport in the world, and one supporting the opposing position that it is not. For shorthand purposes we can call the former position “affirmative” (i.e., yes, soccer is the best sport) and the latter position “negative” (no, soccer is not the best sport).

Affirmative Position Evidence

For the World Cup soccer championship in 2014, there were 909.6 million viewers for at least 30 minutes of the games. That same year, There were 111.5 million viewers around the world for the Super Bowl (Charles Doty, Beutler Ink website, an international marketing firm, accessed June 18, 2018).

Negative Position Evidence

In 1900 the average number of goals in a World Cup soccer game was 4.6. By 2010, that number had fallen to 2.4. “This is a worrying trend. Due to advances in defensive strategies, it is possible that we may witness goals dying out altogether” (Chris Anderson, professor of statistics, Cornell U., Slate.com, May 13, 2013).

Teachers have used these argument builders to build their own model arguments, on both sides of the issue, using these pieces of evidence.

Teachers have typically worked in pairs to share with each other the arguments they have built. We focus on the formulation of the argumentative claim, seeking as always an “equidistance” between the generality of the position statement and the granular detail of the evidence, and (even more so) on the argumentative reasoning, about which I’ll say more below. I then post my model, and teachers compare it to their own, focusing on and analyzing points of difference.

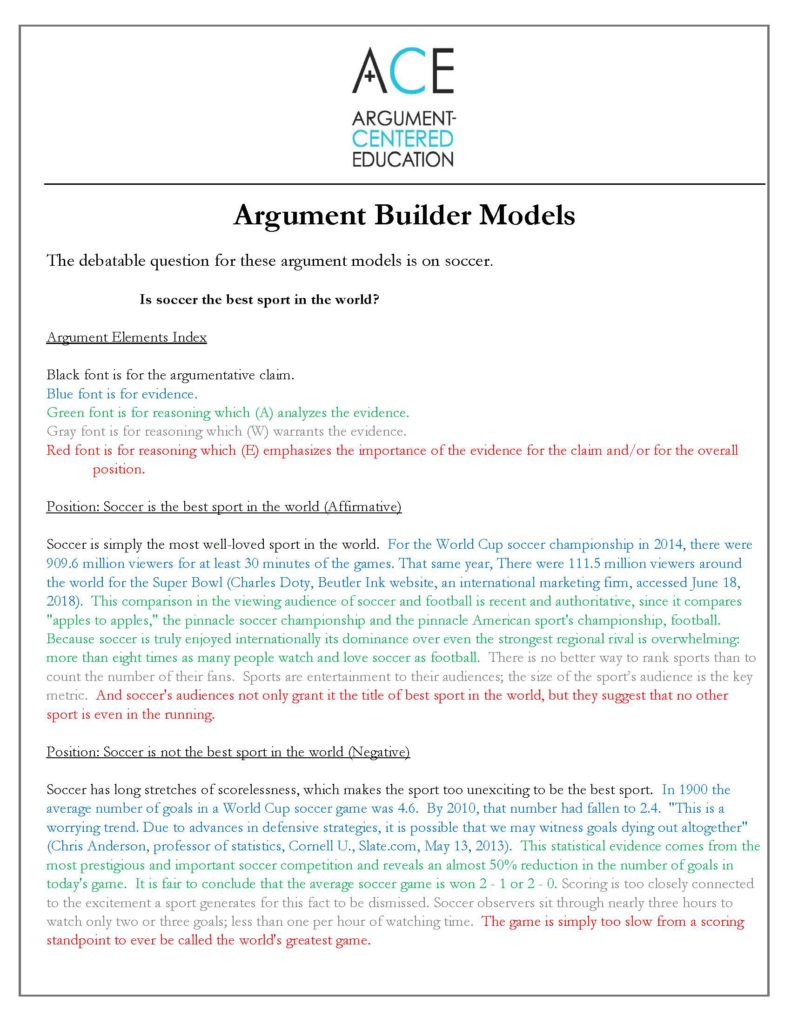

Argument Building Models

I have brought together the two argument models on the affirmative and negative sides of the soccer issue in a single document, one that indexes by color the elements of an argument that they comprise.

Color-Indexed Elements of Argument

Black font is for the argumentative claim.

Blue font is for evidence.

Green font is for reasoning which (A) analyzes the evidence.

Gray font is for reasoning which (W) warrants the evidence.

Red font is for reasoning which (E) emphasizes the importance of the evidence for the claim and/or for the overall position.

I will be posting over the summer on the AWE-some steps and sequence of argumentative reasoning included in this argument model indexing. But here is a short-form explication. The first step in argumentative reasoning is to analyze the evidence. This is often confused by students for paraphrasing, but it is actually “paraphrasing with a point,” or “pointed paraphrasing.” The point, of course, is to accentuate (A) what in the evidence is most directly and authoritatively supportive of the claim. Next, the evidence needs to be warranted (W), in Stephen Toulmin’s language. This means that the writer or speaker should identify the principle, standard, criterion, or point of logic that justifies for the reader or listener that the evidence actually substantiates the claim, and that the claim actually substantiates the overall position. Finally, argumentative reasoning should include emphasis (E) of the importance of either the evidence or the full argument to the overall position. In other words, the writer or speaker should include a response to the unstated So what? question that they should expect the critical reader or listener to harbor.

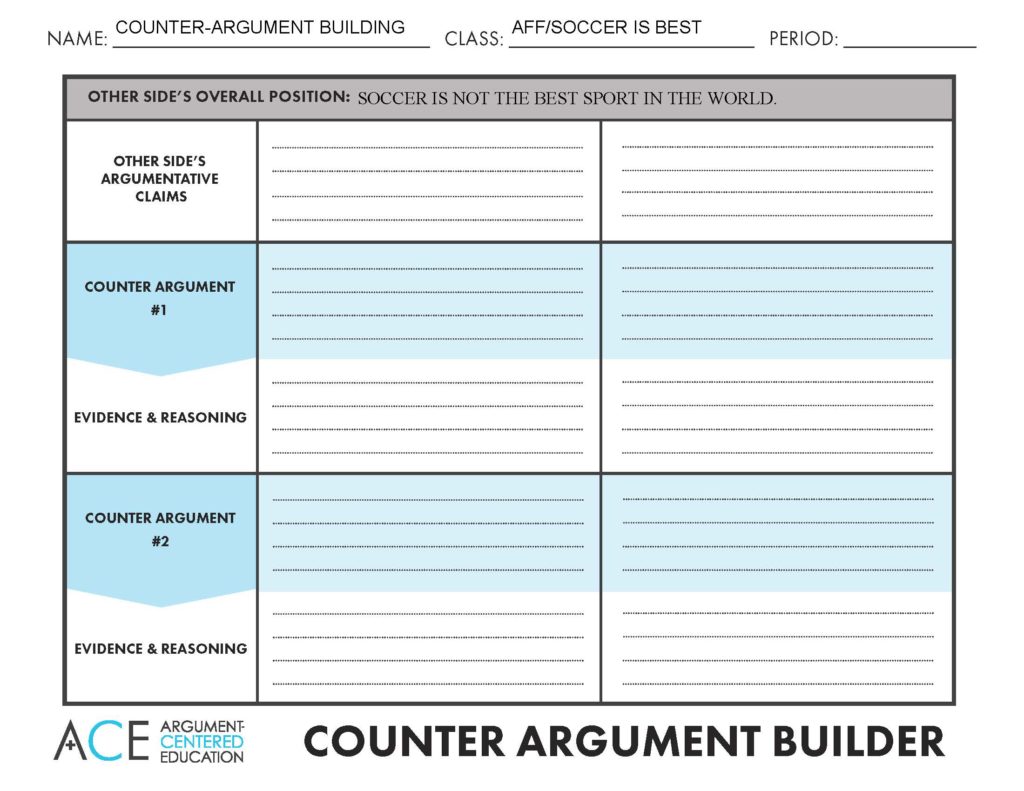

Counter-Argument Building Exercise

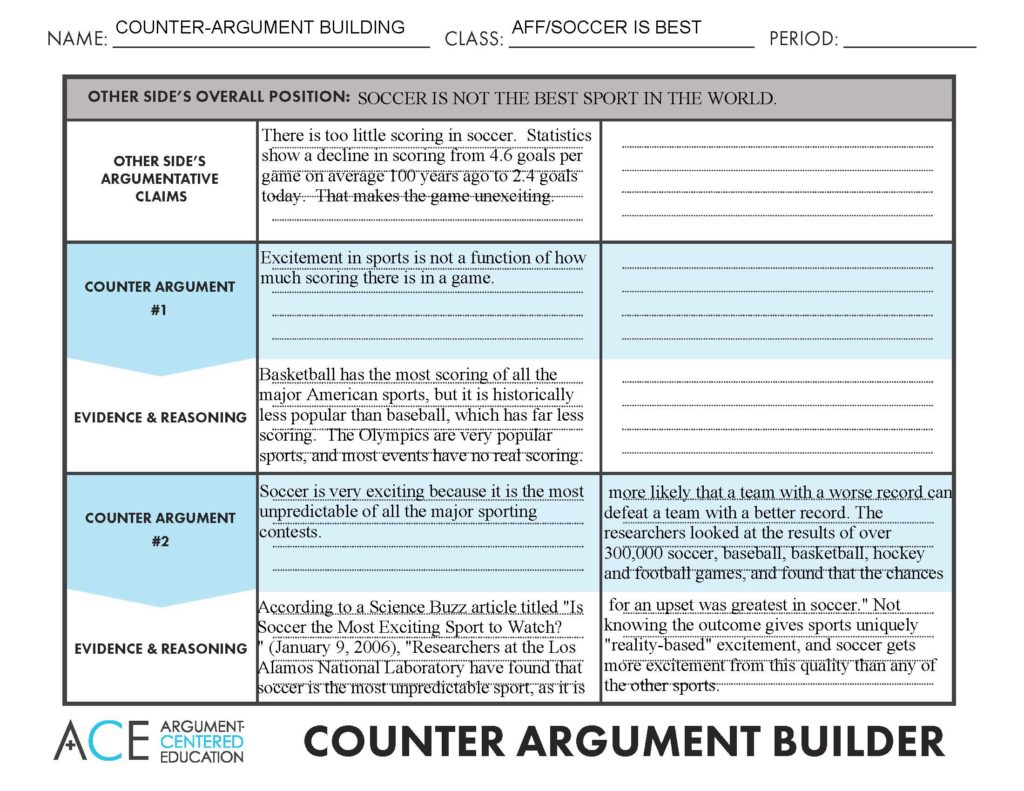

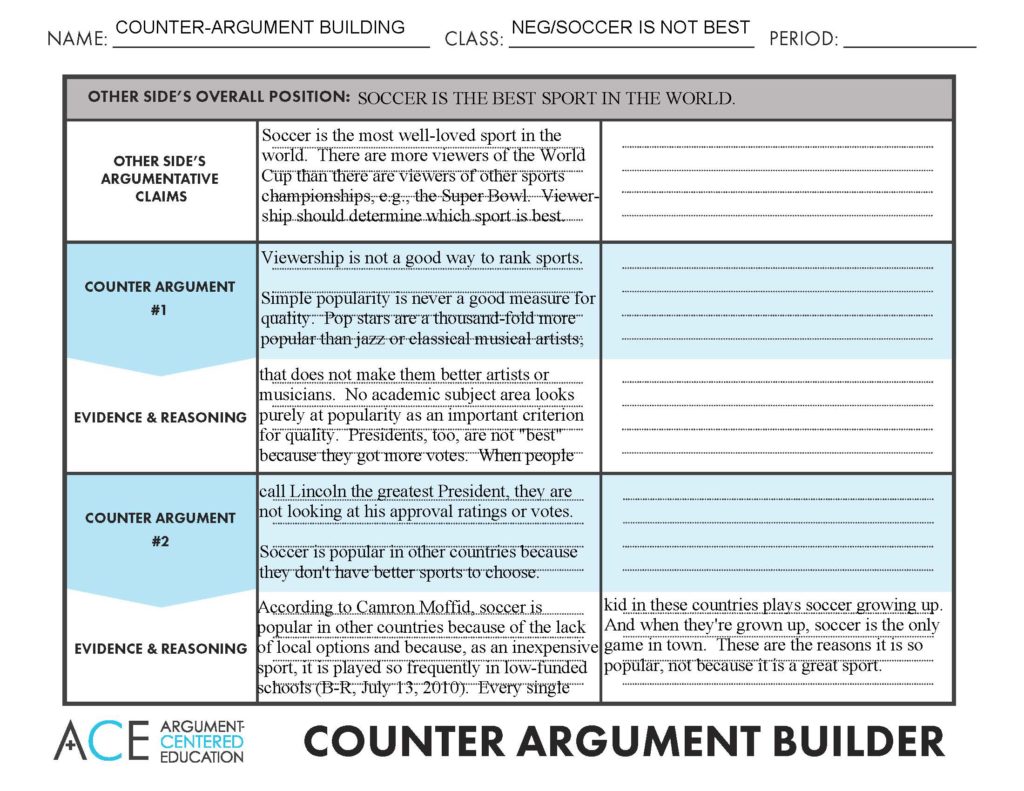

We then conduct together a similar exercise on the flip side, building counter-arguments against the arguments we just created. Teachers use these adapted counter-argument builders to create two counter-arguments to each of the arguments they created on the soccer issue.

Teachers are encouraged to build each of the two kinds of counter-arguments against each argument. One kind of counter-argument is critical. Critical counter-arguments critique the evidence and reasoning of the argument and typically do not include their own evidence and reasoning. The other kind of counter-argument is independent. Independent counter-arguments do contain their own evidence and reasoning. Their counter-claims sometimes are pointed more at the other’s side’s overall position than at the original argument’s claim. To build independent counter-arguments, teachers need to do a little research themselves to find evidence that would support separate counter-claims contradicting their original arguments.

Counter-Argument Models

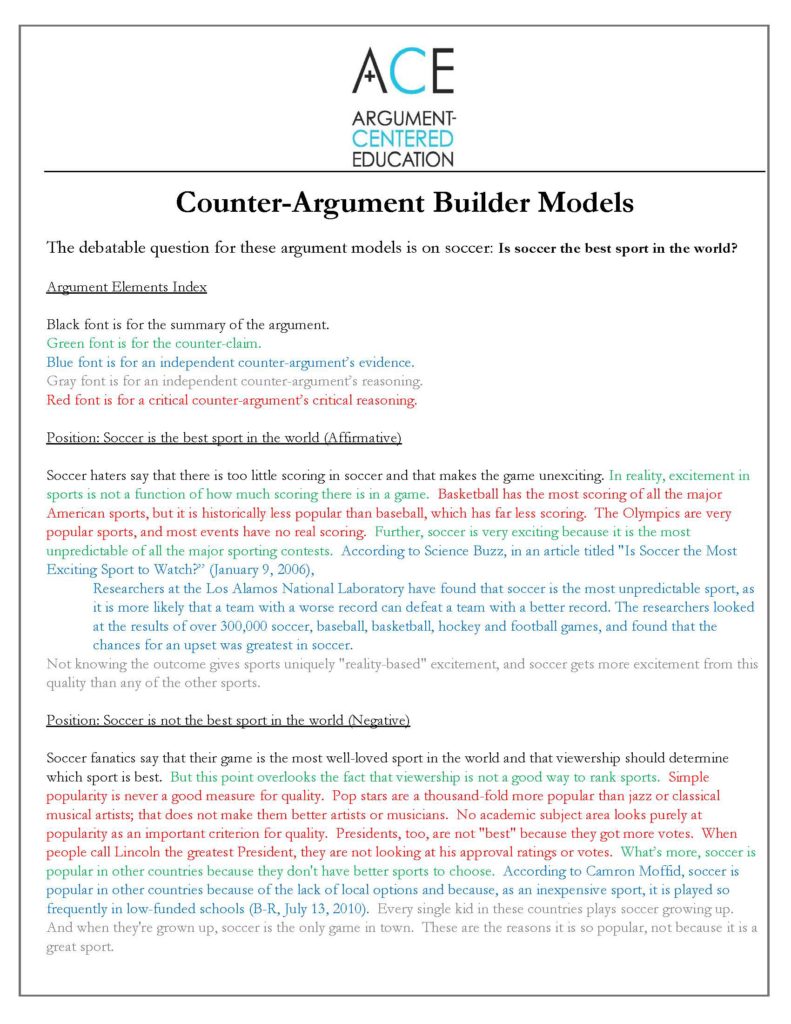

Just as with the built arguments, teachers share their counter-arguments in pairs, discussing which features of their respective work is more successful, and homing in on differences between their counter-arguments. I then project my counter-argument models

I’ve brought together the counter-argument models into a single-page document, adding transition phrases to create full refutation paragraphs. This model document includes its own color indexing. The colors are the same as with the argument models, but they represent different elements, so use of this document needs to be carefully explicated.

Color-Indexed Elements of Counter-Argument

Black font is for the summary of the argument.

Blue font is for an independent counter-argument’s evidence.

Green font is for the counter-claim.

Gray font is for an independent counter-argument’s reasoning.

Red font is for a critical counter-argument’s critical reasoning.

This post is already plenty long, so my sharing of some of the analytical discoveries that partner teachers and I have been making as we work through their argument and counter-argument building and compare it to the models above will have to wait until my next post on The Debatifier.