The Sad State of Presidential Debating? Blame the Judges

By Andrew Brokos

People familiar with my background in debate always assume that election season must be an exciting time of year for me, a rare moment during which debate is front-page news. The truth is just the opposite: I consider all of the grandstanding and empty rhetoric an insult to the activity that I love, and it pains me that these travesties are shaping America’s idea of what a debate should look like.

In November, Les Lynn wrote an excellent piece about the lack of debate in the so-called presidential debates. Sadly, the events that have occurred since have done more to corroborate than to refute that argument.

Lynn’s piece considers the history of presidential debates and their critics. He ultimately puts the responsibility for improving the quality of the debates on the participants, concluding that, “the debaters themselves have the burden to critique and refute the positions and arguments advanced by their competitors.”

In this piece, I would like to consider why presidential candidates consistently fail to step up to this responsibility, and what role we, as teachers and/or students of debate, can play in raising the bar.

The bottom line, as I see it, is that the candidates have no incentive to provide evidence for their own claims or engage rigorously with those of their competitors. Voters don’t reward it, which means that it doesn’t help them win elections.

You can accuse major presidential candidates of shamelessness, ambition, greed, and demagoguery, but you can’t credibly claim that they are bad at playing the game of electoral politics. Professional consultants, in many ways, have the process down to a science, and although there are always new variables to contend with (television, as Lynn points out, or more recently the internet and the use of sophisticated computer systems to optimize fundraising appeals), no one can take votes or media attention away from candidates armed with these tools without doing quite a lot of things right.

Candidates do what they do because it works. Occasionally a “dark horse” emerges to exploit a new technology or strategy to which establishment candidates are slow to adapt – arguably this is what happened in the Kennedy-Nixon debates, where the young and attractive Kennedy won over television viewers even though a majority of radio listeners believed Nixon gave the better performance – but the stakes of the game are too high and the players too talented for such a loophole to go unexploited for long. If substantiating claims, offering detailed refutations of opponents’ positions, and paying more than lip service to legitimate criticisms of one’s own proposals were a winning strategy in presidential debates, someone would be using it.

For years, the stock explanation for the decline of true debating in the presidential debates has been Americans’ ever-shortening attention span, which requires candidates to speak in “sound bytes”. Because Americans will not sit still for a substantive policy discussion, the argument goes, candidates must spoon feed us short, simple caricatures of themselves that can be easily digested and regurgitated by cable news and, more recently, social media.

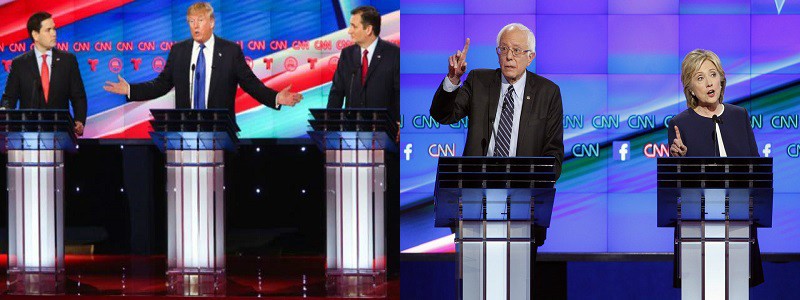

Yet this season’s Republican primaries have consistently set records for the most-viewed primary debates in history. It seems that Americans are willing to watch a debate for an extended period of time, as long as it doesn’t contain too much actual debating.

If we want the electoral process to reward good debaters, and we should, then it is incumbent upon us, the electorate, to care about good debating. This is where the teachers and students of debate come in. No group of Americans cares more about debate than we do, and no one better understands its virtues.

In choosing how we allocate our votes, the money we donate, and the time we volunteer (the three resources for which presidential candidates compete), we should consider not just a candidate’s stated positions but also his or her talent as a debater. I’m not referring here to polished delivery or clever sophistry, but rather to an ability to understand multiple perspectives on complicated issues, weigh advantages and disadvantages, and make good decisions based on the best available evidence.

That’s certainly not to say that we should ignore the extent to which we agree with a candidate’s platform. If nothing else, the fact that a candidate’s positions on important issues differ from your own is evidence that you don’t have a comparable decision-making process.

We should keep in mind, though, that we are choosing a leader for four and quite possibly eight years, and our ability to predict the issues that will be most important during his or her administration is limited. For example, the 2000 presidential debates focused largely on domestic issues, but less than a year later, a terrorist attack led President Bush to make many important foreign policy decisions with far-reaching consequences. Even the domestic issues that ended up consuming much of his attention, such as the delicate balance between security and civil liberties, were not the ones anticipated during the debates.

It’s difficult to predict the issues on which a president will end up having the largest impact, and it’s impossible to find a candidate whose positions are perfectly in line with your own beliefs. This is why it’s important to prioritize candidates with strong decision-making abilities, who can stay calm under pressure, respond to rapidly changing conditions, weigh new evidence quickly, and grasp many facets of complicated issues. These, of course, are among the most important skills inculcated by debate.

Tyler Cowen, economist and author of the Marginal Revolution blog, proposed some interesting suggestions during the 2008 election season for bringing candidates’ decision-making prowess to the forefront. Chief among them is to “[a]llow all candidates to watch a short debate of experts — with a fraud or two thrown in — and ask them to evaluate what they just heard and why they reached the conclusion they did.”

Tests like these cannot, by themselves, convince voters to care about true debate and its incumbent skills, but they would at least send the message that these skills are important, and give voters the opportunity to consider them as they choose a preferred candidate.

Meanwhile, it is up to us, debate’s foremost advocates, to reward candidates’ debate prowess and to convince others to do so as well. If informed debate really is one of the cornerstones of democracy, then we, as teachers and students of debate, bear the great responsibility of ensuring that that torch is passed to the next generation.

Andrew Brokos was a nationally competitive debater in high school and college. He is the founder and former director of the Boston Debate League and a member of the Bay Area Urban Debate League’s Board of Directors. He blogs about poker (and occasionally debate) at ThinkingPoker.Net and co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast.