The North Korean Nuclear Weapons Crisis — An Argument-Centered Approach

This is the first of a short series of posts that reflect work that we have done this summer to prepare argument-based units on social science issues of particularly strong interest to secondary and middle schools, going into the 2017/18 school year. This post looks at an argument-centered unit on the North Korean nuclear weapons crisis, what outgoing President Barack Obama warned incoming President Donald Trump would be the single greatest foreign policy threat and problem of his presidency.

Overview

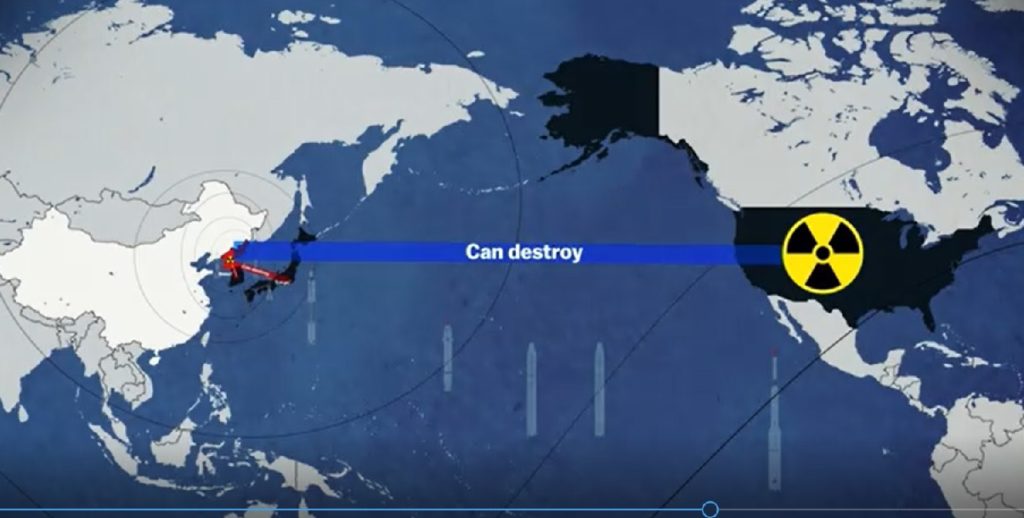

On July 4th – not coincidentally, American Independence Day – North Korea successfully tested an inter-continental ballistic missile (ICBM), a rocket with a range of about 5,000 kilometers and able to reach far into the American mainland, perhaps as far as Chicago. Eleven years previously, in 2006, North Korea successfully tested its first nuclear warhead. In the intervening years North Korea made a full-bore national commitment to building additional and even more powerful nuclear weapons, and developing a delivery system that can reach the country it calls its greatest enemy, the United States. This past summer, North Korea announced and appeared to prove to the world that it is a current threat to incinerate the major cities of the U.S.A., a threat status that came about much more quickly than any Western military experts predicted.

The Korean War of 1950 – 1953 divided the Korean Peninsula into the Western-allied South, with its capitol in Seoul, only 40 miles from the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in the middle, and the Communist North, with its capitol in Pyongyang. Ever since then, North Korea – which never signed an official end to its fighting against the U.S. in 1953 and considers itself at war even today – has pledged its violent hatred of and enmity toward America, along with its intention of reuniting the Koreas under its leadership (even though its population is only one-eighth, and its economy one-hundredth, the size of the South’s). Given this geopolitical situation, a nuclear armed North Korea is causing a great deal of concern and anxiety, not only in average Americans but in foreign policy and military experts of all stripes.

President Barack Obama told Donald Trump, on the day of his Inauguration, that the emerging crisis being caused by North Korea’s obtaining nuclear weapons that are increasingly powerful and able to reach the United States, is our country’s single greatest foreign policy threat. Those words are being born out, and experts and policy-makers are now trying to determine what should be done to respond to the challenge of North Korea, that has emerged as a crisis of the present rather than the future. There are many positions that have been advanced in this debate, but – in addition to the general consensus that there are no easy answers – two poles on a continuum in the argumentation have become clear.

One pole argues that the United States must remove the capacity that North Korea has to attack the U.S. with nuclear weapons, including if necessary the use of military force. The supporters of this position believe that the American military will likely either have to “surgically strike” North Korean nuclear missile sites, or perform a full-scale invasion of the country to overthrow the current regime of Kim Jung-un (North Korea’s dynastic “supreme leader”). The other pole argues that the United States should accept that North Korea is now the world’s ninth nation to possess nuclear weapons, and that we should attempt to “contain and deter” Pyongyang. The objective of this policy is to try to limit the size of the north’s nuclear arsenal and make the country too afraid of our overwhelming response to use nuclear weapons against us or our allies in southeast Asia.

Debatable Issue

Should the United States contain and deter North Korea as a nuclear power, or should it use whatever means necessary, including military force, to eliminate its ability to threaten the U.S. with nuclear weapons?

Sources

The textual and visual media sources for use in this unit are combined into our Media List.

To make it easier for our partner schools to access and screen crucial video documentary shorts, we have downloaded them and embedded them here, ordered according to where they appear in the Media List.

Selected Passages and Infographics

We incorporate the use of Selected Passages and Selected Infographics documents to scaffold students’ evidence selection and research skills. We use them more extensively with students less experienced with academic argumentation, and less extensively with students more experienced.

Here are the Selected Passages and Selected Infographics documents for the North Korean nuclear weapons crisis argument-centered unit.

Claims and Counter-Claims

Another scaffolding method and teacher resource we incorporate (as an instructional option) are sets of possible claims and possible counter-claims. These have a wide variety of uses: they can be distributed to sides in a Refutation Two-Chance activity, to facilitate getting to the refutation stage of the game; they can set up an Close Evaluation of Arguments activity; or they can help students get started in their argument building or argument writing.

It is always a solid foundational strategy for teachers to walk into an argument-centered unit — on any content they are teaching — with a set of claims and counter-claims that students can make and support on the issue. Having these sets of possible arguments and counter-arguments ensures that the issue as you have framed it is balanced and focused enough to generate viable claims on both sides. To produce these sets you also need to have at least mentally scanned through the content resources and identified evidence that students can find and use to support these arguments. And finally these sets help guide your organization of content instruction around argument. They are, in short, vital argument-based instructional resources.

Applications

As with other argument-centered units, there are a good number of argument-centered applications that can be used to engage students in the academic work students should be asked to do to activate and demonstrate their learning about the North Korean nuclear weapons crisis.

Argument Essay

Students can simply be required to write an extended argument essay that requires them to put together their ideas and weigh in on the issue of the North Korean nuclear weapons crisis.

Carefully read and annotate the attached set of secondary-source document excerpts. Use information from at least four of the sources in a coherent, well-developed essay that has an introduction, argumentative body, and conclusion. Your essay should take a clear position, stated in a thesis, on the issue. Your thesis should be supported and developed by 2 – 3 arguments. Each argument should have a claim, evidence, and reasoning, using one or two pieces of evidence from the set of sources. You should also address and refute at least one counter-argument, either in a separate paragraph or in your argument paragraphs.

Other Argument-Based Activities and Projects

Lucy Calkins and her colleagues, in her 2013 book The Research-Based Argument Essay, affirmed the value of conducting oral argumentation and debates in class prior to writing.

We’ve come to believe that it would be advantageous to students if we found opportunities throughout the day to immerse them in a culture of debate, or argumentation (in the best sense of the word). And we believe that it would invigorate the school day to find many opportunities, often, for students to take and defend positions, to learn from argument and counterargument. The research is clear that if students have opportunities to do the work orally that we hope they will learn to do as writers, this is advantageous to them.

These activities and projects can substantially improve and deepen students’ organization, critical thinking, use of evidence, and effectiveness in engaging with the other views and ideas on the issue. Or they can stand on their own as a summative assessment or unit project on the issue of the North Korean nuclear weapons crisis.