The SAT Essay: An Argument-Centered Strategy

Overview

Taking an argument-centered approach to preparing for and to writing the SAT Essay may seem like a no-brainer. After all, the prompt, which is always the same, asks you to explain how a passage’s author builds their argument, to analyze the rhetorical techniques that they use to persuade their audience. The prompt always suggests to consider the author’s use of evidence, reasoning, and stylistic elements in the passage. These are all features of course of argumentation. But since the prompt also tells you quite clearly not to make an argument about the topic of the passage (“Your essay should not explain whether you agree with the author’s claims . . .”), the form of writing you’re being asked to do is generally called rhetorical analysis and it is usually taught as something quite different than argumentation.

That seems to us like an overreaction to the easily avoidable prospect of your mistakenly arguing for or against the author. What you’re actually being asked to do in the SAT Essay is take apart the author’s essay very much from an argument-centered place. You’re being asked to identify what the author’s arguments are and how the author makes them. It is still all about argument. And it is actually easier than having to make arguments that respond to the author’s arguments (especially since you aren’t given any additional sources to draw on, and the topics of the passages are, while not obscure, certainly ones that would require some research to build arguments about). Easier, too, than having to evaluate the author’s arguments, which you are also explicitly told you should not do; in fact, the construct of the SAT Essay implicitly asks you to accept the author’s arguments as effective and persuasive.

This strategy suggested here for preparing for and writing the SAT Essay embraces its situatedness within academic argument, rather than asserting or imposing a mystifying, artificial distinction. In doing so, it is well aligned – possibly better aligned – with College Board’s system of scoring the SAT Essay. Its scoring is based on three domains, each one applying a 1 – 4 score (by two graders, so each SAT Essay actually receives a grade of up to 8 points for each of the three domains). Reading is a domain that assesses how well the student writer comprehends the passage, including its nuances. Writing the essay using this argument-centered strategy puts the passages arguments first, so it is inherently well situated to score well on an assessment of your detailed understanding of the passage. The analysis domain focuses on how well the student writer identifies the important elements and components of the arguments and says interesting things about how they work to make the argument stronger. All of this should be very familiar to students studying in an argument-centered classroom. Writing is how well the student puts their own essay together – sentence structure, mechanics – which prominently includes paragraphing; this argument-centered strategy suggests that, in addition to short introduction and conclusion paragraphs, you organize the body paragraphs around the arguments (or responses to the counter-argument) made in the passage. This helps establish a consistent, clear, but not overly formulaic structure for your essay.

The Strategy

There is a four-step argument-centered strategy that can be used to write the SAT Essay.

Step One: Label the prominent uses of evidence (E), reasoning (R), and style (S) in the passage.

The first thing you will do, regardless of your strategy, is of course read the passage carefully. Using an argument-centered strategy you should do so with pen in hand, indicating in the left margin with an E, R, or S (which you can also index in the prompt, with an E, R, and S in the margin) when the author notably uses evidence, reasoning, or style in their writing.

Evidence is fairly easy to spot, especially for students who are learning in an argument-centered classroom, though it can be grouped into several familiar categories. Statistics or any quantitative data are the most obvious category of evidence to take note of – when you see numbers, it is likely the author is offering evidence to support an argument. Other categories to look for are facts or information, with or without numbers, where the author is making reference to what they are presenting as objective, indisputable reality (as opposed to their reasoning, which is their interpretation of that reality, what it means, why it supports their argument); examples, either historical (more easily recognizable) or current (places, organizations, teams, countries, industries, samples, units – any current comparisons); and quotations from authority, where the author quotes from an expert or authoritative institution to support their argument.

Reasoning can be somewhat more elusive. Its broad purpose, as the SAT Essay prompts note, is to “develop ideas and to connect claims and evidence.” In actual practice, you should look for especially apparent places in the passage where the author is explaining or elaborating their argument. Find your examples of argumentative reasoning in the passage in the sentences that strike you as most compelling, but that are not themselves presenting evidence.

What you are looking for in marking the passage for its use of style are uses of language that stand out, that distinguish themselves either from the rest of the passage or from what you would expect. There are an almost unlimited range of styles and stylistic devices that an author can use, but don’t worry you don’t need to know them all. You only need to note a couple of striking stylistic techniques, and since style itself is so subjective, if you are confident and specific about identifying and naming them, in addition to logical about adding a thought about why they might work on the audience, you will do just fine.

Additional tips:

(1)

There certainly isn’t a single set number of instances of evidence, reasoning, and style that you should label in the passage, but since you will ultimately be organizing your essay around two to four arguments or responses to a counter-argument, and you will want to try to talk about all three argumentative elements (E, R, and S) in each, you’ll generally want to label three or four instances of each in the left margin of the passage.

(2)

Reasoning is the most variable and least readily detectable of the three elements, so do not worry about being too exacting in your identification of it. A lot of what the author is doing in their writing can be defined as argumentative reasoning. Do try to keep it distinct from the passage’s provision of evidence, and focus on sentences that explain or develop a specific reason for the author’s overall position (rather than a formulation of that overall position, itself).

Step Two: Formulate two to four argumentative claims made in the passage

As you are reading through the passage and identifying and labelling its use of evidence, reasoning, and style, you should also be looking for the arguments that it makes for its overall position. The overall position of the piece is always summarized, by the way, in the SAT Essay prompt itself. The prompt will ask you to explain how the author builds “an argument” that . . . and then fill in the rest of the sentence with a summary of the author’s overall position in the passage. The key move that you will make in this strategy is to break the passage apart into multiple (two to four) arguments. This set of arguments can (and often will) include a response to a counter-argument (more on that in a moment).

Professional writers, as you probably know by now, do not flag their different arguments with formulaic signposts like, “My first argument is . . . .” Crude templates like this are useful for student writers learning how to make academic arguments, but student writers work to develop their craft so that they can leave formulas behind, and professional writers have long since done so. Nevertheless, make no mistake: good argumentation means that writers are making multiple arguments for their position and most of the time are addressing at least one important counter-argument to their position. So the job in step two is to identify the arguments being made in the passage to support its overall position, and then to formulate those argumentative claims at the bottom of the second page of the prompt.

Additional tips:

(1)

Understand that there will be different ways to formulate the argumentative claims that are being made in the passage. That aspect of fluidity is inherent to argumentation, in the same way that there will be different, valid ways to paraphrase a passage or interpret an author’s meaning. You just want to be sure that the argumentative claim is being directly supported by some of the evidence in the passage, and that in turn the claim is directly supportive of the overall position.

(2)

If you identify one of the arguments in the passage as a response (or a rebuttal) to a counter-argument, you can label that section of the passage with a C/A (for counter-argument) in the left margin.

(3)

Be sure that the argumentative claims are discrete and separate from each other, in the same way that you do so in your own argument building to support an overall position.

(4)

You should write the arguments (and counter-argument) out in complete sentences, and there should be two to four of them. You should also number the argumentative claims (#1, #2, etc.).

Step Three: Identify each use of E, R, and S as part of one of the arguments or counter-arguments

Now that you have the passage’s use of evidence, reasoning, and style marked in the left margin, and you have the passage’s multiple argumentative claims identified and formulated, you should match the E, R, and S labels to one of the numbered claims or to the counter-argument that the element is being used to respond to. You are looking to try to match each argument with at least one example of each of the three elements you have identified – so, one use of evidence, reasoning, and style for each argumentative claim or response to counter-argument. It is acceptable to have only two elements matched with an argument that the author is making, but it will be problematic to have fewer than two so matched.

Additional tips:

(1)

Inevitably, some elements from the passage will be alignable with more than one argument. Don’t stress about that. Generally, an example of evidence, reasoning, or style should be matched with the argumentative claim it is most proximate to in the passage, but that isn’t an unbreakable rule, and there are times when a sophisticated writer will move back and forth a little in their argumentation. If it is ambiguous as to which argument an element should be matched with, match it with the argument that most needs it (i.e., doesn’t have the element already covered by another example).

(2)

You should also not worry about having multiple examples of an element matched with a particular argument. You will only need to use one example when you write about that argument.

(3)

If you have included the response to a counter-argument as one of the arguments made in the passage to support its overall position, you will want to match two or three elements to that counter-argument response.

Step Four: Write the essay, organizing by argument and counter-argument, and being specific in describing uses of evidence, reasoning, and style in each paragraph

Time to write your essay. You should begin with an introduction paragraph that is very brief. I recommend one sentence that introduces the issue that the author’s passage is taking a position on – similar to the role that an introduction has in an argument essay except that (a) you’ll frame the issue here in a single sentence, and (b) you’re framing it as an issue that the author is arguing on, not one that you will weigh in on. The second sentence should state the position the author takes, summarizing the argumentative claims they make. A third sentence in the introduction is optional: if you have a way to sum up the specific way that the author uses each element to advance their overall position, you can mention these in a third and final sentence in the introduction.

The next two to four paragraphs should be organized each around the two to four arguments that you have identified in the passage. Each of these paragraphs should begin with what you can call an analytical claim – or a topic sentence, if you prefer – that states one of argumentative claim’s that the author makes. Or, if it is about responding to counter-argument, the sentence should read something like, “Author X advances her position that __________ by addressing the counter-argument that some people make that _______________.” After this opening sentence, the paragraph should cite each of the elements that the author uses to develop that argument, according to the index matching you did in Step Three. For each of these elements, name the particular way the element is being used (e.g., “Author X uses statistics produced by academic research to support her argument here” rather than “Author X uses evidence to support her argument here”). Then paraphrase or (less frequently) the element (e.g., “She refers to a University of California study that shows a 10% drop in the population of northern cities since 2005, which suggests that there has been a migration to warmer locales [her claim]”). Then, in most instances (unless it will seem redundant) you should insert a short sentence explicating the effectiveness of this specific element (e.g., “Demography is a social science, so academic research, especially from the most prestigious universities, is likely to be persuasive to the audience”). Do this for each of your two to four body paragraphs, drawing on the prep work that you have done in the first three steps.

Your essay should end with a short conclusion. You should restate the overall position that the author argues for, and it should in a manner that uses new language identify a pattern in the author’s use of rhetorical elements – the elements that you have been analyzing throughout the body paragraphs – to develop this argument.

Additional tips:

(1)

Be sure to be specific about the way that the element is being used. So, never say simply that the author uses evidence to support his claim, but rather name the specific kind of evidence.

(2)

This is most challenging with reasoning. With evidence, there are a relatively small number of categories that all argumentative evidence can be placed within. With style, while there is a vast range of style, and a long list of stylistic devices used by writers, there is a subjectivity and an openness about the way writing style is described; so if your description is clear and specific, it is very unlikely to be evaluated as right or wrong. With reasoning in this context, you want to stay close to the line of thinking, the logic, that the writer is using in the passage and the way that the author heightens the significance of the evidence they are using the argument they are making. Check the examples on the “demonstrations” resource.

(3)

To heighten your chances at a very top score in the reading and analysis domains, you should insert into each body paragraph a tailored reason why the author’s use of elements will be especially persuasive to the audience, and try to include somewhere in the essay reference to the sequencing of arguments in the passage (e.g., “Having started with quantitative data, Author X will get more buy-in from her audience for her use of an anecdote to support this argument”).

(4)

When citing the evidence that the author uses you should paraphrase most of the time. SAT Essay graders want to see that you have assimilated an understanding of the passage, and you can do this most directly by putting the information in the passage in your own words. That said, you should include at least one quotation from the passage in your essay.

(5)

You have 50 minutes to complete the SAT Essay. You should spend 20 – 25 minutes on the first three steps, which implies that you will need to practice the SAT Essay to get to a quickness and efficiency that allows you to get through these steps in no more than half the fully allotted time. You will not likely need more than 25 minutes to write the actual essay because the prep work fully organizes your writing before you start it.

(6)

If you are running out of time in the actual writing of the essay, you should drop an argument or two and consolidate to two body paragraphs.

(7)

You should not extend past the 25-minute mark in your preparation. At the half-way point, begin writing what whatever preparation you have; it will likely be enough to position you well for a good score.

A Demonstration

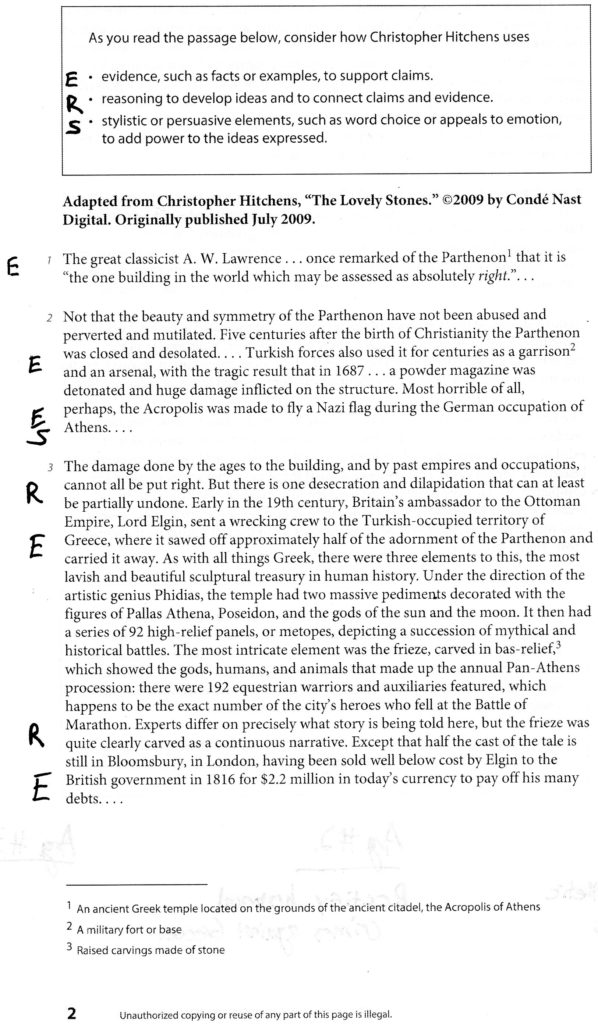

We’ll look at and closely explicate a demonstration of the first three steps being conducted on an SAT Essay sample from practice exam #6, released by the College Board. The passage is written by Christopher Hitchens; he argues (as the prompt tells us) that the original Parthenon sculptures should be returned to Greece.

The first short paragraph is a good example of a professional writer creating their own rules. Hitchens is an especially well-regarded stylist. He opens this passage with piece of evidence – a quote from an authority on ancient Greece – before he has even stated his position or made his first argumentative claim.

The second paragraph lists historical crimes against Greece that included abuse of the Parthenon, associating these national crimes with Britain’s appropriation of the Parthenon sculptures. The paragraph also includes the “horrible” imagery of a Nazi flag flying on top of the Parthenon, asserting Nazi ownership over this cultural property of the Greeks. This is a stylistic heightening of the historical evidence in the paragraph because it creates the most vivid, and the most extreme, visual image in the readers imagination.

Most of the third paragraph is devoted to the details of the way that the sculptures in the Parthenon have been split up and separated; there is too much detail here to be usable in a very short, quickly written essay. The paragraph does end with some numbers: the amount of money that Lord Elgin received for the Grecian stones he sold to the British government “to pay his debts.” This is evidence of a kind of theft, perpetrated from personal greed. Early in the paragraph, Hitchens reasons that even though most of the prior crimes against the Parthenon cannot be undone, returning the sculptures to the Parthenon is one “desecration” that can be rectified. He appeals here to the audience’s moral sense, their innate desire to do what can be done even if the world cannot be made perfect. And late in the same paragraph Hitchens reasons that though historians have not deciphered the entire symbolic meaning of the sculptures and the intricacies of their carvings, they do know that they make up “a continuous narrative.” We pulled this section out to mark as reasoning in part because of the contrasting clauses: “Experts differ . . . but quite clearly . . .” This language of disagreement, of distinction-drawing, is one of the markers of argumentative reasoning.

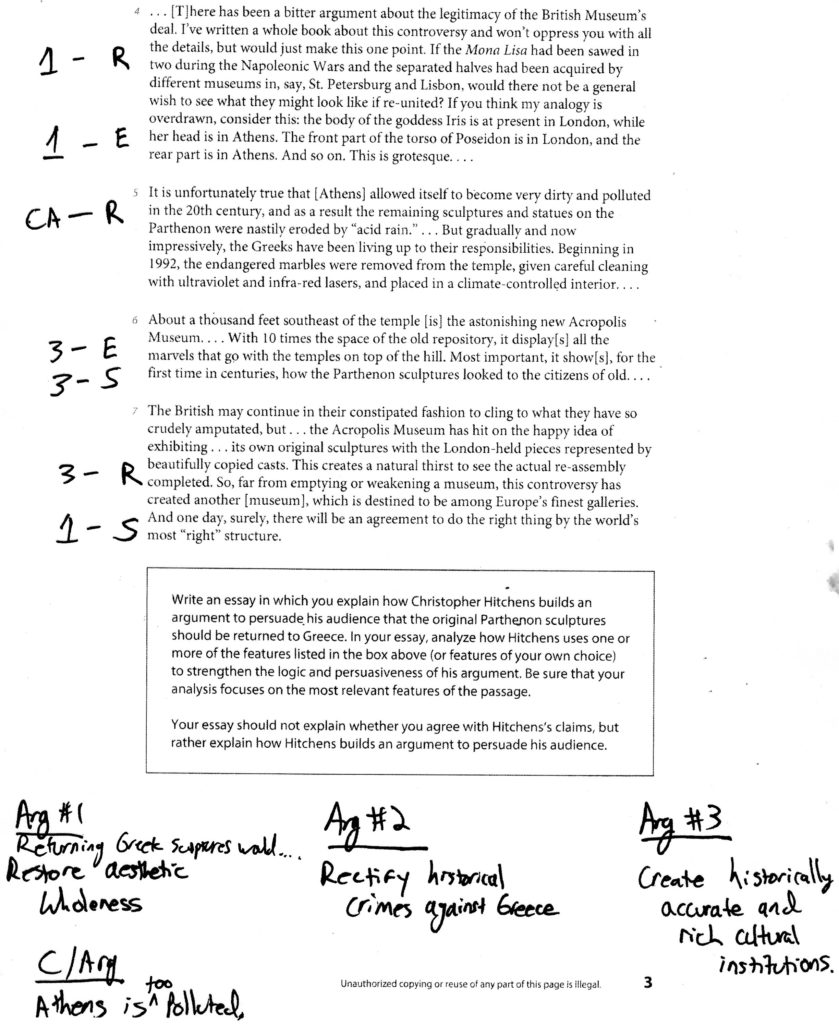

Another such marker appears near the middle of the next paragraph. Hitchens offers a hypothetical example to try to make the evidence he has laid out about the separation of the sculptures that much more convincing. He suggests that if the Mona Lisa had been similarly cut up and taken by different nations to different museums there would be a strong desire to see the pieces reunited and the painting restored. We didn’t index it, but this passage also includes use of understatement as a rhetorical device (the technical term for understatement is litotes). “A general wish” is much less than would be the public will to see this most famous of Da Vinci paintings made whole if it were torn apart, as Hitchens well knows. The fourth paragraph ends with a particularly “grotesque” example of a statue from the Parthenon that has been broken apart and whose pieces exist in different world capitols.

The fifth paragraph includes what is readily defined as a counter-argument, along with a response to it. Hitchens concedes that Athens is a heavily polluted city, tainted by acid rain. His concession here enhances his ethos as a credible, reasonable voice, acknowledging a legitimate concern that some might have about returning all of the Parthenon sculptures. But, he answers, Greece has since 1992 been assiduous about properly cleaning, storing, and protecting its valuable ancient marbles. There isn’t really any hard evidence in this paragraph, though, to support its rebuttal to the counter-argument, which is basically why we’ve labelled it reasoning: Hitchens posits Greece’s new concern for these objects and reasons from there to an answer to the counter-argument.

The penultimate paragraph includes a factual detail about the new Acropolis Museum: it is ten times as large as the previous museum for these relics in Athens. This counts as evidence, even if we don’t know yet what the argumentative claim it is that the evidence supports. The short paragraph then closes with another use of imagery, a stylistic device, as it asks the reader to imagine that in the new museum the sculptures will look exactly as they did to citizens of Athens nearly 3000 years ago.

The final paragraph incorporates a new example of reasoning. It provides the significance for the reader of Athens’ work with the impressive new Acropolis Museum. The fact that the Acropolis is putting up plaster casts of the missing sculpture pieces, to help fill its vast space, only further whets the public’s appetite to see these wondrous pieces of historical art fully and authentically brought back together. Be reminded that reasoning in an argument often has the function of instilling the evidence and the argument with significance, addressing the So what? question (the Greeks have built a new museum and new plaster casts, so what? so why does that mean we should return the Parthenon sculptures?) Then the whole passage ends, as the SAT Essay passages often will, with a play on a double meaning of the word “right” – right as in morally correct, right as in harmoniously designed – a play that links back to the very beginning of the passage to bring the piece to closure.

Step Two is a little bit more succinct, since we have done so much of the thinking and significance-interpreting in Step One. We need to generate two to four argumentative claims from the rhetorical elements we have identified and named.

Looking at the first piece of evidence in the first paragraph, we have this concept of “rightness.” A. W. Lawrence is of course referring to aesthetic rightness. And that meaning echoes with the stylistic element used at the end of the passage, which we analyzed two paragraphs above. With two elements present both supporting the same reason for the overall position we can go ahead and formulate a claim. So one argumentative claim – our first – is the following: “Returning Greek sculptures would restore their aesthetic wholeness.”

The evidence in the second paragraph pertains to a reason that is distinguishable from the first reason for the overall position. Hitchens emphasizes the historical crimes that have been perpetrated against Greece and their cultural and artistic treasures in his supply of historical examples as evidence in paragraph two. There is even a strong use of imagery as a stylistic element in this paragraph, as we discussed above. Even though we have two elements in place for a second argumentative claim, in reading on just a bit in the passage we find an example of reasoning that is also well aligned with this claim. Hitchens moves from the evidence in the above paragraph to reasoning that appeals to his audience’s moral sense – to their innate view that the world should do what can be done to right a past wrong. The second argumentative claim is ready to formulate: “Giving Greece back its rightful sculptures would rectify historical crimes against the country.”

The next piece of evidence we couldn’t quickly identify a use for: it is the long passage about the detailed ways in which particular sculptures that have been broken up had original symbolic coherence, had an original meaning Our indexed reasoning in the third paragraph gives us a clue: Hitchens is reasoning that when the sculptures are placed together, rightfully, they told a continuous narrative. It isn’t fully clear yet what argument this evidence and reasoning will support, but it does not seem to be either the claim that restoring the marbles will rectify past crimes or complete an aesthetic whole (assuming we distinguish between aesthetic and historical significance, as the passage seems to do).

The final piece of evidence in paragraph three clearly relates back to the second claim: Lord Elgin took the Greek marbles for mercenary reasons, apparently. And the fourth paragraph has evidence and reasoning that both point to the value and logical justification in piecing back these sculptures to recreate the aesthetic wholeness and beauty that they once contained. So, they both support the first argumentative claim.

The fifth paragraph contains a counter-argument and a rebuttal, both of which we have discussed above. So we added the counter-argument to the list of two to four arguments at the bottom of the second page of the prompt. It is quite possible to identify the (relatively) new Athenian program of protecting their ancient art work as evidence if we credit the specificity and exactness of their “careful cleaning with ultraviolet and infra-red lasers” as objective information. That would give the rebuttal in this paragraph two rhetorical elements, reasoning and evidence, allowing your writing of it to parallel the other paragraphs.

The sixth and seventh paragraphs triggered for us the third argumentative claim, and the use of the evidence and reasoning in paragraph three. The sixth paragraph discusses the new Acropolis Museum and its considerably expanded size. The seventh and final paragraph reasons through the public’s hunger and implied right to see the original pieces in a great historical and cultural institution. Part of what they would do in front of these restored sculptures would be to read, interpret, and learn from them. When we looked quickly back to the evidence and reasoning in paragraph three, particularly the idea that the “frieze” tells a continuous historical narrative, we had our third argumentative claim: “Locating all of the original Greek sculptures together would support historically accurate and cultural institutions.” The use of imagery at the end of the sixth paragraph is usable as part of the development of this third argument.

Note that with four arguments we wouldn’t need to include all of them in the actual essay. And formulating the third claim was less a matter of reaching a number and more an instance of confronting evidence and reasoning in the Hitchens passage that didn’t fit well with the claims we already had. Different passages are going to make a different number of arguments, differently configured.

With all of the important evidence, reasoning, and style elements identified and named, and the arguments formulated, it is a quick, backward-designed task to match the elements with its proper argument. We’ve already thought this through, and in fact when in the above quick internal deliberations we became clear that we were adding an argument it would have been fine to put the number of the argument next to the element during Step Two.

In writing the actual essay, we would write a three sentence introduction: (1) introduce the controversy over Grecian sculptures taken by other nations, including Britain’s taking the “Elgin marbles;” (2) state that Christopher Hitchens’ “The Lovely Stones” takes the position that the marbles should be returned to Greece, since they are an aesthetic whole, Greece was victimized historically, and full sculptures would establish important cultural and historical institutions; and (3) to convince his audience, Hitchens uses varied forms of evidence, reasons by making moral and logical appeals based on hypotheticals, and stylistic elements, especially vivid imagery. Then the body paragraphs start with the argumentative claim that Hitchens advances, followed by the evidence, reasoning, and style element that he uses to support the claim. We can get to two or all three of the argumentative claims, and the counter-argument and rebuttal are optional. A conclusion will restate the position that Hitchens takes and give a final takeaway emphasis on the most important rhetorical techniques he uses across the arguments.

This argument-centered strategy produces a thorough handling of the SAT Essay. It isn’t necessary to cover in the actual essay writing all of the options that the conceptual moves that it makes uncover for us. And a key to making it work for you is to practice the first three steps on numerous practice exam essay prompts, to ensure that you can squeeze them into 25 minutes. You should practice your actual essay writing, too, beginning perhaps by writing an essay in 25 minutes based on the preparation that this demonstration has taken you through.

Conclusion

Not every student chooses to write the SAT Essay. Those who don’t write usually say that it’s optional, but the real reason is often that they don’t feel adequately prepared to succeed. This argument-centered strategy will help those students feel ready, and will help the students who currently feel ready take an approach that is likely to result in their best possible score.

What’s as important as this, an argument-centered approach to the SAT Essay can be integrated into instruction in a regular English or social science class, so that learning how to approach this exam overlaps entirely with learning to write for college and beyond. The SAT Essay is just another forum for academic argument; it angles in on academic argument by having students analyze the argumentation of distinguished professional writers. Argument-centered classroom learning in the 10th and 11th grade can view this forum as one of the ways their learning culminates and is shown off. In a future post we will include an additional demonstration of this strategy at work, and we will post additional practice exam essay prompts, so that you can integrate these as writing exercises, if you choose.