An Activity to Introduce the Academic Argument Model

Early in the school year, it is a good idea to introduce the fundamental academic argument model to students who may not be fully familiar with it, or to refresh students’ understanding even if they have worked with it extensively in the past. The ubiquity of the academic argument model — not only in argument-centered instruction, but throughout schooling — justifies spending some precious early-year, culture-establishing time on this task. This activity is designed to provide students with this (re-)introduction.

Overview

An academic argument is an evidence-based viewpoint, idea, response or answer you put forward in school (thus the word “academic,” which means “related to learning or school”). The ability to make good arguments, and to be able to respond to other arguments that contradict or differ in some way from your own, may be the single most valued and important skill in all of education, K – 12, college, and even graduate school. The other side of the coin is being able to hear, read, understand, analyze, and evaluate academic arguments. You do this all the time when you read informational articles or essays, watch a video, try to make meaning out of a story, or have a discussion in any subject area about some important question. And making arguments does start with questions, or what are called debatable issues. That isn’t surprising, since so much of what we do in class is ask, think about, and then try to respond to questions.

What we mean by a model – as in “the academic argument model” – is a consistent design or structure, one that is what we use to create something ourselves, something we copy. Think of a “model student” – someone who is always prepared to learn, who is inquiring and curious, who thinks critically, who tries hard – or even a “role model” – someone who has characteristics that we try to emulate, to have ourselves.

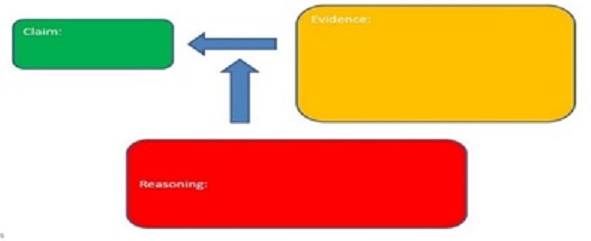

The model of an academic argument was created by a philosopher in the middle of the 20th century named Stephen Toulmin. Thinking about arguments, though, and how we communicate and discuss what we believe to be true, and even how we determine what is true, goes back to the beginning of Western civilization, to ancient Greece, and especially the famous philosopher Aristotle, who lived in the 4th century BC. Toulmin said that all arguments need to have a claim, evidence, and reasoning. The argumentative claim is a viewpoint, interpretation, or conclusion that is supported by the rest of the argument. Evidence is factual, objective substantiation for the claim. And reasoning is the speaker or writer’s explanation as to how the evidence proves that the claim is true. Reasoning is often left out, but don’t leave reasoning out of your arguments: all three components of an academic argument are very important!

This is how Toulmin configured the components of an academic argument in a drawing:

When you are presenting a viewpoint, interpretation, or answer in school, in response to an open or debatable question or issue, and you want to do it well, you should always put it in the form of an argument, with all three components: an argumentative claim, evidence, and reasoning. The order sometimes varies – sometimes we put the evidence first, for example – but the important thing is that all three components are there.

Now, the next step is subjecting arguments to critical thinking. In argumentation, this means seeing if there are any arguments that might oppose, disagree with, or even just differ from our argument. These opposing arguments are called counter-arguments. Thinking about – or reading or listening to — counter-arguments, and then trying to respond to them is the process of refutation, and it is crucial to the value and importance of argumentation as a process. Ultimately, we want to evaluate the strength of competing or clashing arguments, in order to come up with what we believe is the truth on a given issue or question or topic. Ultimately, we have to decide what we believe is true, and that is best done through argumentation. But it all starts with the fundamental academic argument model, and making arguments using it.

Let’s look at a couple of examples. We’ll start with one that isn’t so “academic.” But arguments aren’t only made in school, so it’s a fair place to start.

Argumentative claim:

Subway is the best fast-food restaurant.

Evidence:

The Subway menu includes a large variety of fresh bread and vegetables on the menu.

Reasoning:

Fresh bread and vegetables are an important part of a healthy, balanced diet. One of the most important factors in selecting a restaurant is how healthy its meals are.

The evidence above isn’t “sourced” (we don’t know how the speaker knows that this is true), but it is presented as factual, so it meets the criteria for evidence. Someone could dispute it if they had reason to believe that the bread or vegetables served by Subway are not fresh. That would be a counter-argument. Reasoning here explains why it is that this evidence is proof or strong support of the argumentative claim.

Here is another example, one that is more “academic.”

Argumentative Claim:

Global climate change is being caused by human activity.

Evidence:

According to the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, “Ninety-seven percent of climate scientists agree that climate-warming trends over the past century are very likely due to the burning of fossil fuels, primarily in coal plants to create electricity and in cars and other gas and oil burning vehicles.”

Reasoning:

Even though there can never be absolute certainty in matters of climate science, when a consensus of scientific experts exists on a question like humans’ impact on climate change, we should accept it as scientifically verified.

Activity

For each of six arguments, students will provide the missing component (or components). When asked to provide evidence students should make up what they think would look like or sound like actual evidence (though be sure to warn them: do not do this when you are building your own arguments!). When they complete the six arguments, students should find a partner who is also finished, and they should share and discuss their completed arguments. They should try to decide which argument is stronger, truer, better supported, more convincing, when there are differences, and why that is. The activity can conclude with a sharing-out classroom-wide discussion. Teachers should collect and assess the completed arguments, looking for:

Argumentative claims that are focused, clear, and include a reason for the writer’s position

Evidence that is factual, objective, and aligned with the argumentative claim

Reasoning that explains how the evidence proves the claim, and answers the implicit question, Why does this evidence matter, what makes it important?

This is a sample argument that students will complete in the activity.

1.

Argumentative Claim: American middle and high schools should use a year-round calendar.

Evidence: Other developed nations that have a year-round calendar do significantly better on both math and reading in 6th – 12th grades than the United States does on the Program for International Assessment (PISA) testing done every three years, according to the 2016 report produced by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Reasoning:

Students will provide this missing component, to complete the argument