Responding to and Refuting Conflicting Interpretations — Junot Diaz’s ‘Drown’ (Part 2)

This post — which focuses on a method of teaching students to respond to and sometimes refute literary interpretations that conflict with their own — is the second part of a two-part look at an argumentalized unit on Junot Diaz’s first collection of stories. Part 1, on teaching students to analyze passages closely through argument, can be found here.

Recognizing the Importance of Engaging with Counter-Arguments

To write college-directed interpretive essays in literature courses students need to learn to address counter-interpretations – i.e., counter-arguments. An important standard applied to college-level academic work is that interpretations and other types of literary readings are only worth making if they are addressing an unsettled question, an open and probing and resonant matter: a debatable issue. It follows that a student’s interpretive position on a debatable issue, and the arguments they make to advance it, cannot be so obvious or logically deductive that they unarguable.

College-level academic writing, therefore, addresses counter-arguments, and it attempts to responds to those counter-arguments (it is never enough merely to acknowledge that other viewpoints exist, the response to them is crucial). When choosing counter-arguments – as applied to literature, counter-interpretations or counter-readings – it is important that students select the most compelling reasons that might be advanced against their arguments. They should be taught to avoid choosing easily addressed, “straw man” counter-arguments. Raising those in their writing has the opposite effect that they intend: weak counter-arguments lead the reader to conclude either that the writer is hiding from the stronger, better supported reasons to disagree with their conclusions, or that they are unaware of stronger counter-arguments because they haven’t fully thought through their position and thought critically about it.

Responding to the best reasons you might be wrong – imagining what Deanna Kuhn at Columbia University calls what a “missing interlocutor” might say in disagreement with you – strengthens and refines your own arguments and makes them more compelling and convincing, thoughtful and lasting.

Responses to counter-arguments fall into two categories. Students can rebut or refute the counter-argument. The writer or speaker does this either by critiquing and undercutting its evidence or reasoning, or by presenting other, more compelling and significant evidence and articulating a reading of this passage that serves to refute the counter-argument. In the first option — the critique of the counter-argument — often this means in literary argument that the writer disputes, undercuts, or critiques the reading that the counter-argument gives to a passage. Reads the passage differently, in other words.

Alternatively, a writer or speaker can make a strategic concession. A strategic concession acknowledges the validity of the counter-argument – up to a point. Strategic concessions can often be very persuasive because they signal the reasonableness and inquiry-purpose of the writer or speaker. The key to making a strategic concession work, however, is to be able to analyze and explain that the portion of the counter-argument that is being conceded does not negate one’s overall position, that it is compatible with their original reading of the work.

Counter-Arguments and Responses in Students’ Interpretive Writing on Drown

As a reminder, the debatable issue that our partner school chose to use for the summative interpretive argument writing assessment focuses on the work’s understanding of and attitude toward the immigrants’ pursuit of the American Dream.

Viewed through one lens, Drown is an immigration story, the story of a family’s relocation in the latter half of the 20th century from a Latin American country, the Dominican Republic, to the northeastern urban United States, in search of a better life, in search of the American Dream. It is in this way a story of an experience that many millions of immigrants have shared. What is the work’s take on the immigrant experience? According to Drown, is the American Dream a worthy goal, one that through hard work and ambition Latin American immigrants have a realistic chance of achieving, or has immigration to the U.S. been an empty promise, one that has failed to deliver a better life for the common Latinx immigrant?

In the unit students go through a process of identifying textual passages that support a position on the question, and then cluster this evidence into arguments. For each of the three argument clusters and claims that they develop and commit to, they then develop one strong counter-argument, backed by a piece of evidence from the text. In response to the counter-arguments, you then are asked to use an Evidence Collection Refuter to refute the counter-arguments. Their refutation can be critical — going back to the evidence in their cluster explaining how it is more significant, or re-interpreting the counter-argument’s passages — or their refutation can adduce additional evidence from the text (akin to a counter-argument that is “independent” rather than “critical”). Or students can respond to the counter-argument, but not refute it. One response is to strategically concede it, identifying what they agree with in the counter-argument (and possibly too what they disagree with), analyzing how the concession does not undercut their overall position. That is a crucial feature of any response that students make to their counter-arguments: the response has to carefully explain how it is that the original position remains valid, how it can nevertheless be sustained despite the validity of the counter-argument.

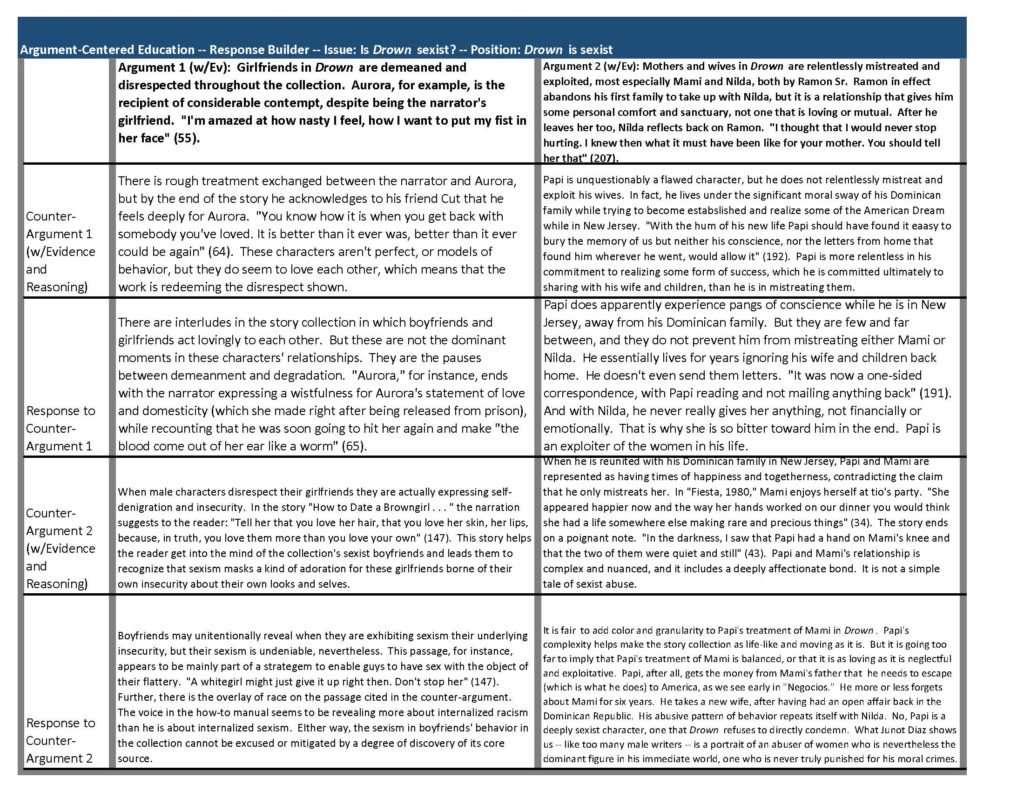

The Evidence Collection Refuter is one important resources in a systematic run-up to the final production of the summative interpretive argument writing assessment. Students need to take seriously the working out of their interpretive ideas and arguments on these resources, but then they also need to take seriously the conversion of the ideas on these organizers into writing actual essays. Another stone on which students step toward their argument writing summation in this argumentalized unit on Diaz’s Drown is the Response Builder. Cognizant of the instructional force of good models, we collaborated with our partner high school to produce this Response Builder model, using one of the other four debatable issues that guided the full unit. This debatable issue asks whether the story collection contains traces of the sexism of the milieu that it describes or, instead, it inscribes a feminist criticism of the sexism present in the stories’ settings and secondary characters.

Weaving these resources — and more — we succeeded in organizing instruction throughout the unit around interpretive arguments at the center of insightful, meaningful, college-directed readings of this important literary work — readings that students express orally and in writing and, very importantly, readings that are articulated in relation to the sometimes conflicting, contrary readings of their peers.

As an important post-script, The New Yorker a Personal History piece just published written by Junot Diaz in which he discusses, for the first time in public, a sexual assault he suffered as a boy and the psychological, emotional, and professional consequences that this trauma has inflicted on the author.