Integrating NWEA Preparation Organically, Using an Academic Vocabulary Log

There may be no more quietly disparaged term by teachers, in my experience, than “teaching to the test.” It doesn’t get openly stated most of the time, but it is a phrase in the air and in the back of minds at a whole lot of faculty gatherings, department meetings, and teacher-administrator conferences. It might do well to have the phrase come in from the out on the edges, though, since the ambiguity in exactly what is meant by it seems to keep people apart in professional discussions on assessment. “Test-prep factories,” where they exist, seem to clearly pummel and reduce education in worse than Gradgrindian fashion. If this is teaching to the test, it is educational regress, if not malpractice. On the other hand, good teaching practice has always included measurement of student learning on content and skills taught; a stalwart and widely well-regarded system like Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe’s Understanding by Design guides teachers to backwards-plan units and lessons from assessments of academic objectives, a more professionally careful way of building in “teaching to the test.”

It seems to me that as long as we are administering assessments — or having to administer them, in some instances — and that they are consequential for students, we should as educators make their presence in our classrooms as coherent and as integrated as we can. That means that we should ensure as best we can that all of the assessments our students are taking are serving to measure the curriculum and instruction that we are planning, designing, and delivering.

One common standardized (though its originators don’t like to call it that) assessment common to most of the middle schools that Argument-Centered Education works with is the NWEA MAP (Northwest Education Association Measurement of Academic Progress) assessment. This is a test that many schools administer two or three times a year — beginning of the year, end of the year, and for some schools mid-year. It is taken seriously by Chicago Public Schools, and other districts with which we work, as an approximately accurate measure of middle school student academic growth each year, and year-over-year. That has led us to work to integrate some of its academic profile, its academic objectives, into our argument-centered strategies that we collaborate on and share with our middle school partners. If you want to get to know something fundamental about a subject area, a curriculum, a pedagogy, an assessment, the place to start is with its language, its characteristic vocabulary. The discourse applied by any strategy or system in education is its most reliable guide. Education theorists have been convincing, for instance, using recent neuroscience to explain that limited command over subject-area discourses have been a key constraint on American NAEP literacy scores over the past 20 years.

If you want to get to know something fundamental about a subject area, a curriculum, a pedagogy, an assessment, the place to start is with its language, its characteristic vocabulary. The discourse applied by any strategy or system in education is its most reliable guide. Education theorists have been convincing, for instance, using recent neuroscience to explain that limited command over subject-area discourses have been a key constraint on American NAEP literacy scores over the past 20 years.

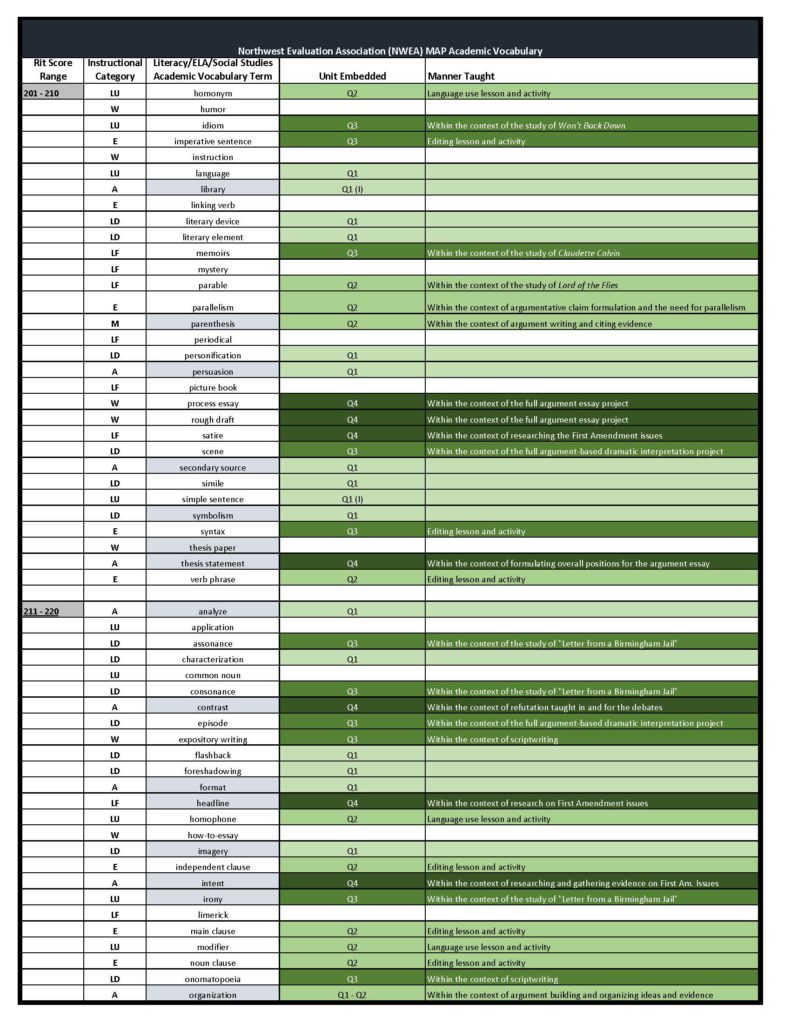

We have tried to build this insight into our work with partner schools. To help our partner teachers integrate with intentionality and planning the academic vocabulary that the NWEA tests, at each appropriate level of individual and grade-wide student achievement, we designed the NWEA MAP Academic Vocabulary Log.

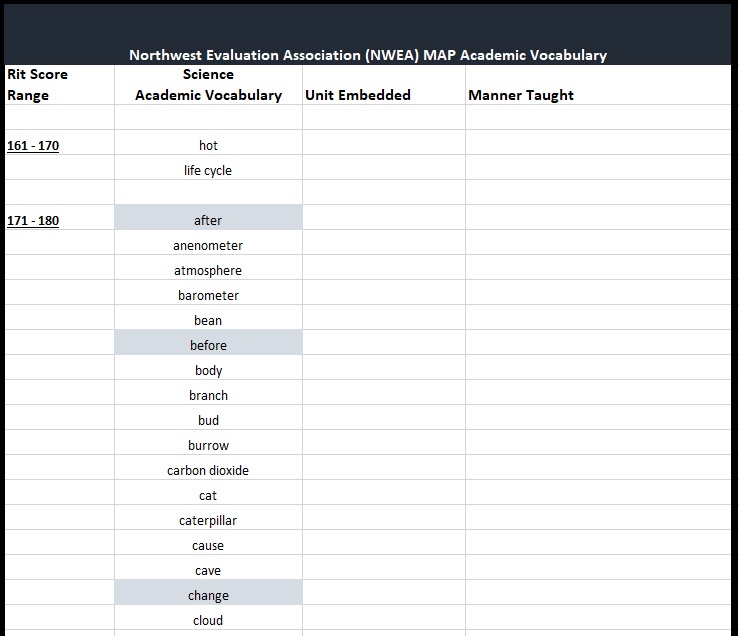

This log has within it all of the academic vocabulary terms that NWEA recommends that 5th – 8th grade students need to know to be prepared to succeed at each RIT score level. They are of course cumulative, so all of the academic vocabulary terms needed to score in the 201 – 210 RIT score level presuppose comprehension of all of the prior RIT score level terms, as well. The full list of terms we mined directly from NWEA resources, in particular the NWEA’s Descartes system.

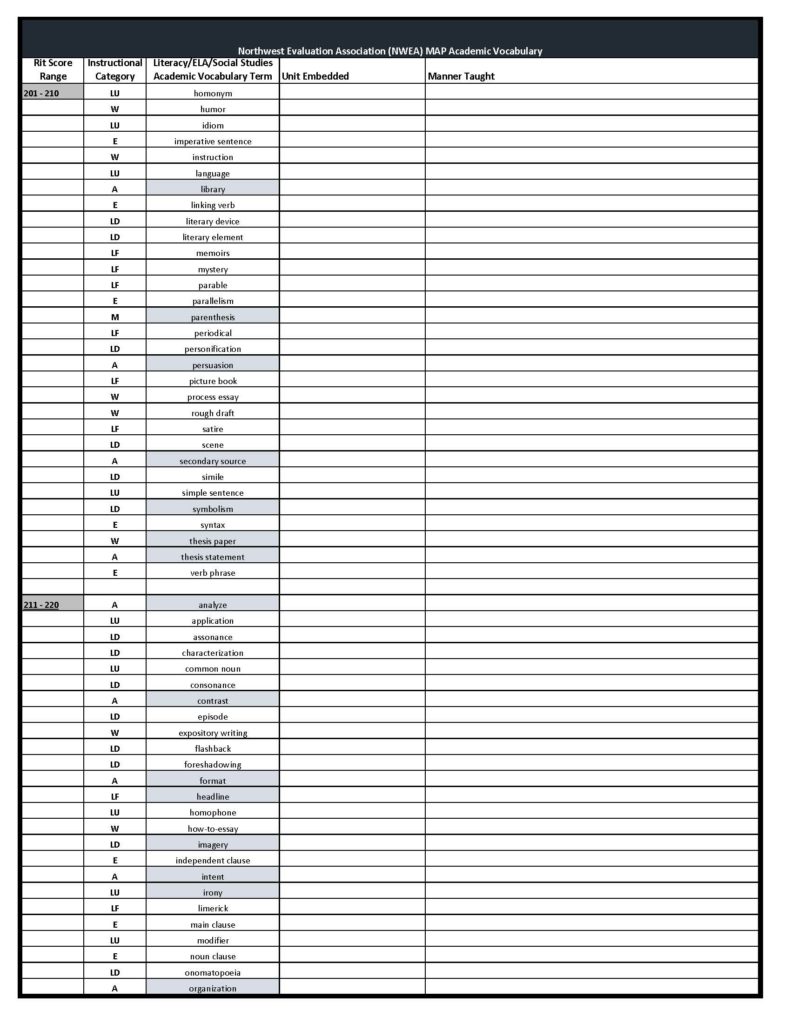

The Academic Vocabulary Log divides the terms into three domains: literacy (ELA and social studies), math, and science, and the version of the log above contains all three domains. We also have a version that is exclusive to literacy, used by partner ELA and social studies middle school teachers.

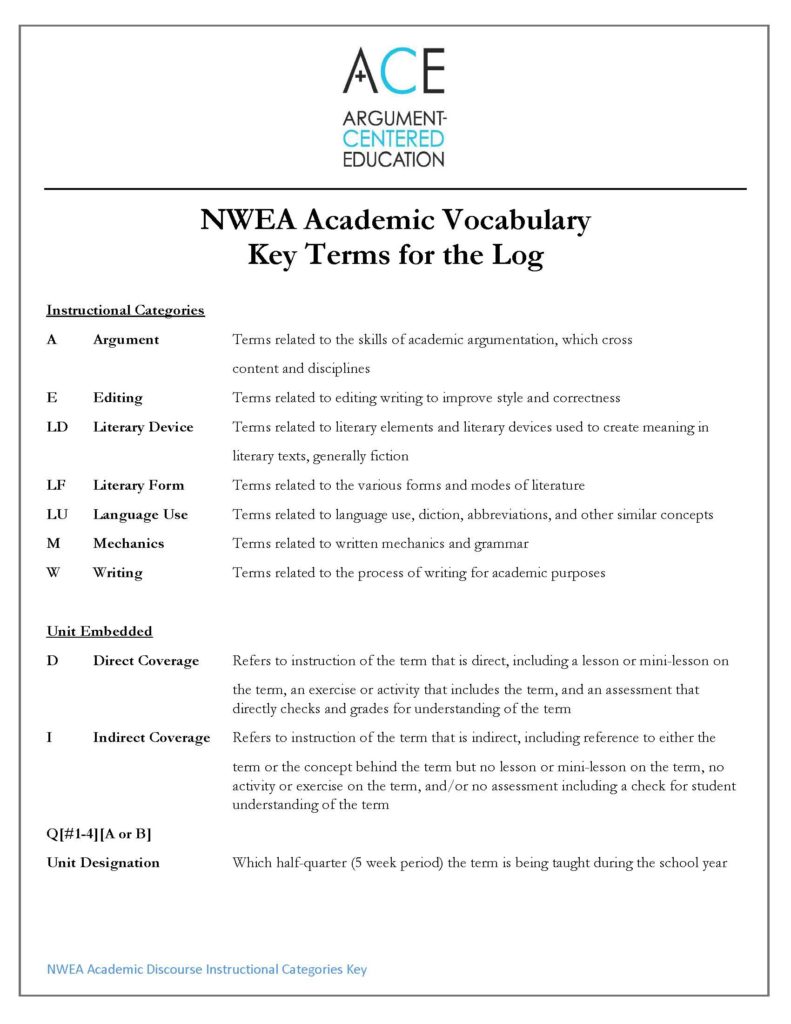

The literacy version is condensed to be print-ready (smaller font, separated into six pages) and therefore more wieldy than the previous format. It also includes an “Instructional Categories” column, whose abbreviations are explained in the key, the last page. Instructional categories divide terms by literacy domain: literary device, mechanics, argument, editing. Having instructional categories enables teachers to cluster the embedding of terms in their units around category, whenever it makes sense to do so. Teachers can include all of the “editing” terms in a unit that includes a full writing project, for instance, or they can do a mini-unit on “mechanics.”

Terms highlighted in blue on the log are explicitly argument-based and should be taught as a part of argument-centered instructional projects. And of course there are many terms in the log that are not argument but can be drawn upon and included in an argument-centered unit or project.

The way that we recommend this document be used is that for each of a teacher’s four or five week units they intentionally plan to embed into the unit some number of these terms. The log enables teachers to record which unit they have covered a term (they can cover a term in multiple units, of course, noting that in the log), and the manner in which they cover the term (e.g., as part of a set of argument-based questions on informational text reading, as part of the introduction to a poetry unit, etc.). Ideally teachers will explicitly teach the meaning of the term they are covering, and require through assessment that students demonstrate their understanding of and ability to autonomously and accurately use the term. In this way the term will be organically embedded within the unit — it will fit within the unit being taught naturally, coming up out of the ground of the content or skills of the unit.

Which of the terms a teacher chooses to include intentionally is of course partly dependent on whether they teach math or science or ELA and social studies — or all of the above. It is also dependent on what their students’ RIT scores are. My recommendation here would be to go one cut (the cuts are in 10-point increments) below their students basic range (leaving off outliers) and two cuts above the students’ basic range. Teachers can try to include as many (perhaps all?) of these terms in their instruction through the year, unless they teach all subject areas, in which case they might try for half of all of these terms.

What this log accents is building in intentional academic discourse and vocabulary instruction based on this NWEA set of terms. And it’s a good set. If students come out of middle school knowing all or almost all of these terms, and being able to use them appropriately, that will carry them a long way toward readiness for a selective enrollment high school and college beyond.

Academic vocabulary is not the only thing that the NWEA MAP assessment is measuring, but it’s an important part of it. Research is accumulating that a person’s vocabulary, and in particular their academic vocabulary, is a very good indicator of their testing performance and at some fundamental level their learning. So though this isn’t the be-all and end-all of professional practice, certainly, it is something that I think is a substantial and worthy part of it.

A few other usage notes, based our experience this year.

Teachers will need to be sure that they know all the terms well in order to embed them properly and teach them well. I had to remind myself what “participial” meant from the literacy page. Math and science have a lot of terms that teachers will likely need to refresh themselves on; some seem obscure to me, especially in science (e.g., heterozygous, transpiration).

Speaking of science, there are great number of content terms in science, about as many as in English and math combined. Anyone preparing students for success in the science portion of the NWEA MAP test is being very explicitly asked to take on a heavier content instructional load than seems normative in my experience at the middle school level.

Teachers should consider color coding their unit entries on the log, so that they can see at a glance when they’ve covered a term, and consider returning to key terms during the year.

The NWEA (like standardized tests at the HS level) use a lot of different terms for the language of argument — e.g., main point for position, topic sentence for claim — and they like to draw distinctions between categories of argument or evidence-supported viewpoint — e.g., is this passage a cause and effect passage or a compare and contrast passage? My recommendation is that we teach students to see the connections here, as well as the language differences, so that they are not thrown off by them. Don’t hide the connections, as in, Now I’m teaching to prepare you for the NWEA MAP test so we’re going to put away the language of argument, but rather say, OK, what we’ve been calling an overall position, the NWEA MAP test sometimes calls the author’s main point. Same thing.

What I recommend is to first identify the RIT score cut bands (the 10-point bands) that most of your students were at as of the previous assessment, and mark that band, and the next two bands up from that band (as growth goal bands).

Here is what an exemplar version of the NWEA Academic Vocabulary Log looks like, from a current partner middle school. See if it makes more sense with the exemplar there. Then consider contacting us to help your department or school implement an NWEA Academic Vocabulary Log for next school year, by working on alignment and integration this spring and summer.

Thank you.