Video Look into Representative MS Classroom Debates this Spring

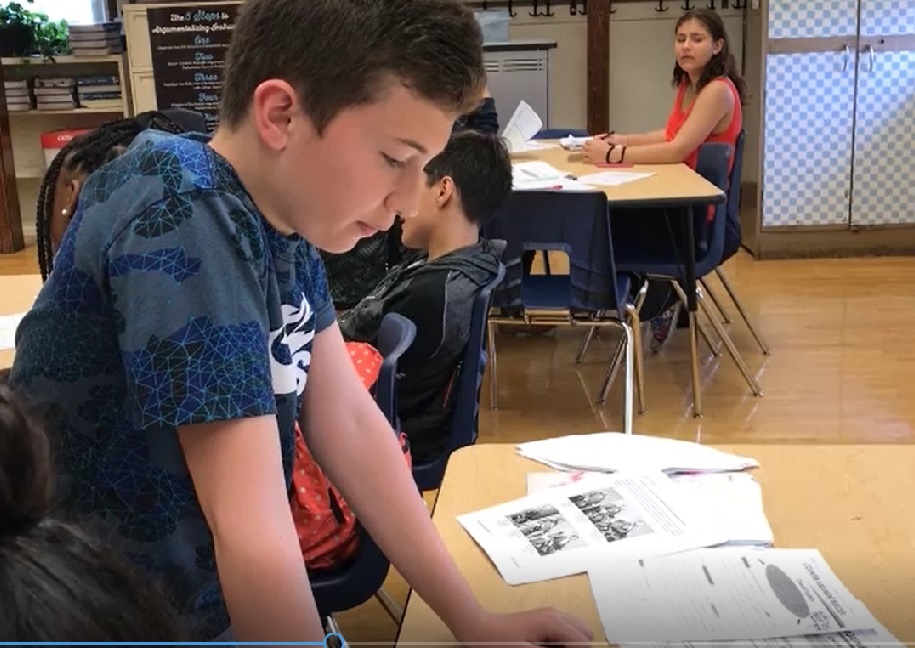

All of the Argument-Centered Education partner middle schools have implemented classroom debating projects this spring semester and I can honestly say that all had verified successes, in some of the same and in some varying ways. The Helen C. Peirce School of International Studies conducted classroom debates in several grade levels; we captured some of the 7th grades table debates in different classes, led by different teachers, and I wanted to share them to demonstrate how representatively successful implementation of MS argument-centered unit can culminate.

With our regular training and support, Peirce MS has attained a highly professional and proficient 5th – 8th grade instructional implementation and management of argument-based pedagogy, and student performance in these regular units that inspires with both what has become normative and with how high the ceiling is for future growth.

Ms. Donna Lawrenz’s 7th grade ELA classes read and processed informational texts on the issue of gun violence and gun regulation in a two-week unit. They then debated this issue:

Should the United States adopt restrictive gun regulation?

Ms. Mel Ferrand’s social studies classes have used Stanford History of Education Group primary documents and other readings to study the Reconstruction Era (1863 – 1880) in U.S. History. The unit culminated in table debates on the issue:

Did Reconstruction substantially advance racial equality in the United States?

Here are a few annotated video clips of the some of the table debates both of these outstanding professionals facilitated, supervised, and assessed this spring.

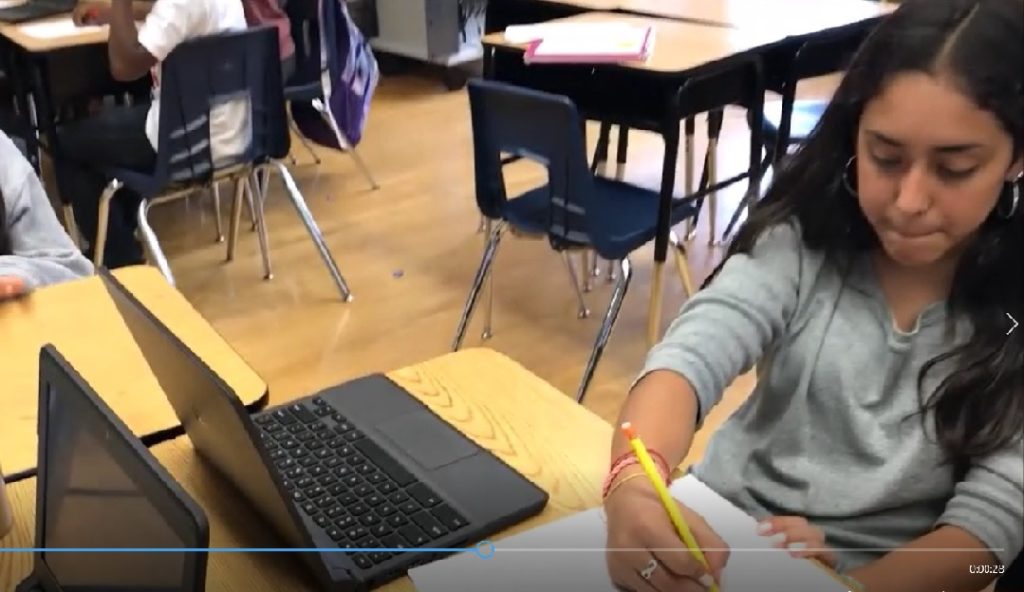

Gun Regulation Debates — Mid-Round Prep

Ms. Lawrenz made sure to give students preparation time (“prep time,” in the language of debate) before their counter-arguments and their rebuttal arguments. You can see in this clip with what acuity and focus students are thinking hard about what they are going to argue to respond to the other side’s arguments. You can see, too, that they are accessing both their flow sheets and their Chromebooks as part of their self-understood need to make their refutation substantive and evidence-based.

Gun Regulation Debates — Counter-Arguments

You can see students grappling themselves, in their own language and with their own cognition, with the arguments opposing gun regulation: responding thoughtfully, with the best thinking they can produce, to the argument that guns can deter criminals, that gun regulations cannot keep guns out of the hands of criminals, that mental illness is the root cause of recent mass shootings, that the Second Amendment should not be changed. There is no substitute for this kind of cognitive strain and processing if we want students to learn about complex subject matter. Debating produces this kind of cognitive strain and processing across the classroom.

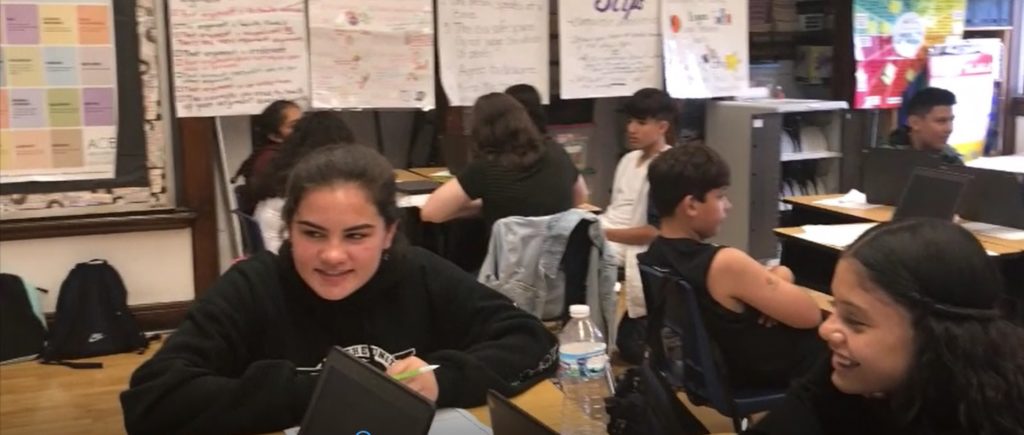

Gun Regulation Debates — Peer Feedback

One of the most innovative aspects of classroom debating and structured argumentation at Peirce is how extensively and effectively it incorporates peer feedback. This is only possible because Peirce has made a commitment to argument across 5th through 8th grade classrooms. This results a great deal of competence and knowledge already possessed by the students’ peers at Peirce who are one grade level above. Here, 8th graders judged and provided feedback on all of the debates. You can hear how specific and substantive this peer feedback is — for example, on the importance of direct and aligned responsiveness in argumentation — and how seriously and with what full attention the students are listening to and learning from their peers’ inputs.

Reconstruction Debates — Case Arguments

This clip — from Ms. Ferrand’s debates on Reconstruction — illustrate several important academic features. The students case (or “opening”) arguments are well constructed and always supported by historical documents used as evidence. All of the students listening are taking close, careful notes on their tracking forms (or “flow sheets”). No one is passive in this classroom; everyone is actively learning simultaneously. And arguments are pointed, with significance, in relation to their students’ overall position on the issue.

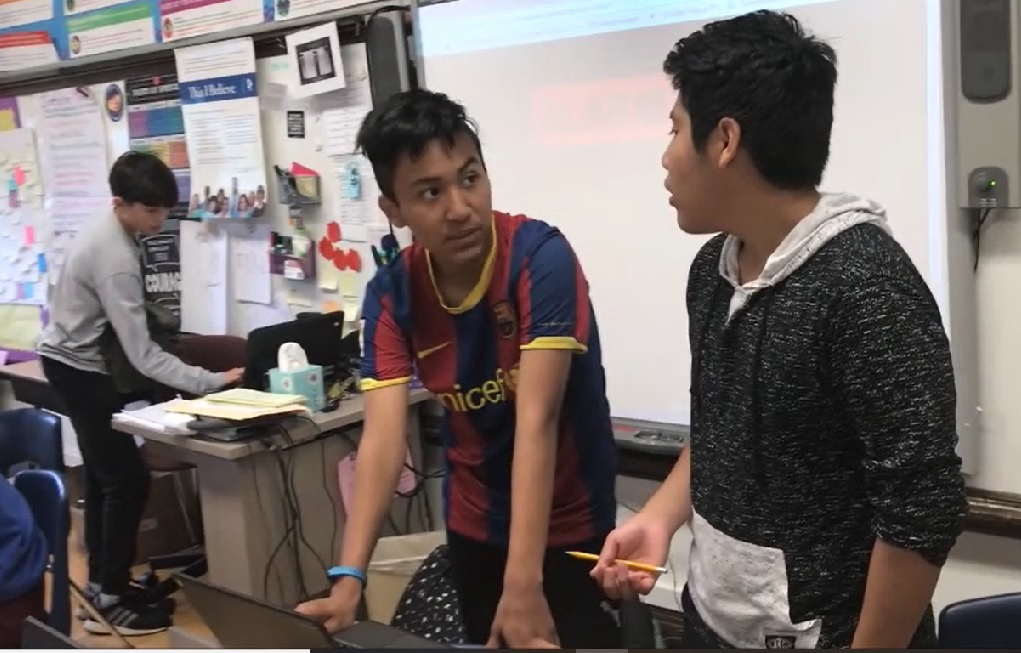

Reconstruction Debates — Cross-Examination

Cross-examination in the table debates format is dialogic. Students are enjoying interacting with each other, probing and testing the other side’s argumentation. And they are taking full advantage of demonstrating a fuller understanding of the historical context and relevance of their arguments, well beyond what they have used to present their arguments in their “case.” Here, too, we see some of the heightened motivation that inheres to debating as a form of learning; yes, this can be overdone, and good teaching means regulating the force of competition and the adrenaline-feeling of defending a point of view that is yours (whether a personal conviction or an adopted one for the “theater” of the debate). But there is no denying that debating infuses these students in these cross-examinations with an additional energy, and one that is being harnessed here for learning.

Reconstruction Debates — Counter-Arguments

Counter-arguments in these classes, too, is flow-based — meaning that it is required to be directly responsive to the arguments of the other side, and that it is borne of critical thinking (as best the students are able to do) about what their classmates are arguing. You can hear, in this clip, a student reasoning very persuasively through how insignificant (in his view) the differences in human rights and personal liberty and dignity were for African-Americans before the 13th Amendment and — largely because of Black Codes and the oppression of cultural racism — after it. Everyone around the table listening to this student (and the others making their own counter-arguments) have to try to fully understand this reasoning and then subject it to their own critical evaluation and reference to their own understanding of what the historical record, reflected in the documents they have studied, supports.

Reconstruction Debates — Rebuttals

Here, students are able to stand up and respond to and rebut the other side’s — their classmates’ — counter-arguments (though in both clips, the position being argued for is that Reconstruction did NOT substantially advance racial equality). One highlight in this clip, too, is how partners in the debates have to try to process, understand, and summarize in writing the way their teammate has of articulating their side’s arguments. They are having the experience, visible here, of experiencing how what should fundamentally be the same position and arguments for that position sound and actually are different: they are working through matters of precision, style, persuasion, rhetoric, evidence choice, reasoning choices, and other shadings and gradations that are important to more advanced levels of literacy.

Ms. Lawrenz and Ms. Ferrand both did an outstanding job managing the implementation of these argument-centered projects this spring. A special kudos was earned by Ms. Lawrenz who — due to her more advanced stage of professional mastery over this pedagogy — helped coach Ms. Ferrand to the successes she herself had with it this semester.