Argumentalizing Chimamanda Adichie’s ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’

Half of a Yellow Sun is an epic historical novel, with a romance novel embedded within it, about the Nigerian Civil War (1967 – 1970). It was published in 2006, by that country’s most internationally celebrated writer, after Chinua Achebe, Chimamanda Adichie. Adichie may be best known to American students for her 2009 TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” which has been watched nearly 4 million times.

Half of a Yellow Sun tells the story of Biafra’s stunted birth as a breakaway, revolutionary southern province of Nigeria and its elimination at the hands of the western-backed Nigerian government. Adichie has said in interviews that she had the ambition in writing this novel to tell the story of Biafra, which she didn’t think had been told from a properly African perspective, but to transform history into art. In this way, she looked to the precursors like Tolstoy and Conrad. Leaders of the Biafran revolution are entangled in the novel with their romantic yearnings and their own clashing ideologies. And the novel depicts war’s weighty and distorting influence on professional lives and ambitions, on relationships between people and nations, and on one’s moral identity.

Half of a Yellow Sun won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2007, given by British critics to the best work of extended fiction written by a woman, in English, the previous year. It was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times. And it inspired Nigeria’s long-reigning laureate of letters, Chinua Achebe, to say this about Adichie:

We do not usually associate wisdom with beginners, but here is a new writer endowed with the gift of ancient storytellers. She is fearless, or she would not have taken on the intimidating horror of Nigeria’s civil war.

A partner school’s English department teaches this challenging novel in a couple of its courses, and I worked with teachers this year to argumentalize the curriculum in their Yellow Sun unit that began after the students had finished the book. We agreed together that we wanted to include the students themselves — mostly seniors, all college-bound, most to highly competitive schools — in the process of establishing debatable questions. So what we did was ask students to generate text-based thematic questions in preparation for a seminar. (The process here I will discuss in a future post; the resource we used for this purpose is worth a close look.) The students turned their questions in for formative assessment and immediate feedback. Students worked to revise their questions and we conducted a student-moderated, argument-focused seminar.

What we were hoping to get from the seminar is exactly what we got. Students didn’t develop their interpretive differences all that far in the seminar. This is typical, because the informality of a seminar leads students generally to hesitate to push their disputes very far. Until an argument-centered culture is fully in place, students are often quick to agree to disagree unless they are pushed into developing their argumentation through a structured format. But what we did get, and in very full form, were a set of interpretive conflicts that students found most compelling and that generated the most pointed differences in the classes. These we turned into debatable issues.

We did some crystallizing and a little bit of academicizing of the disputes that were the centerpiece of these seminars to produce our document of the debatable issues, but the students recognized them quite clearly as their own. We then moved into a developed Argument Exchange, assigning pairs of students issues that they weighed in on the seminar. The Argument Exchange was prepped and conducted over a four-day span of classes, and students built interpretive essays as a summative product, fully developing the ideas in a formal written piece that they had a chance to argue about with their peers in a structured format.

Several classes also incorporated an argument-based inquiry into the differences between war correspondence and the war novel. You’ll recall that these very differences were a prime interest of Chimamanda Adichie herself in writing Half of a Yellow Sun. We collected examples of war journalism from several historical events, including the Rwandan Civil War and the Serbian/Bosnian War.

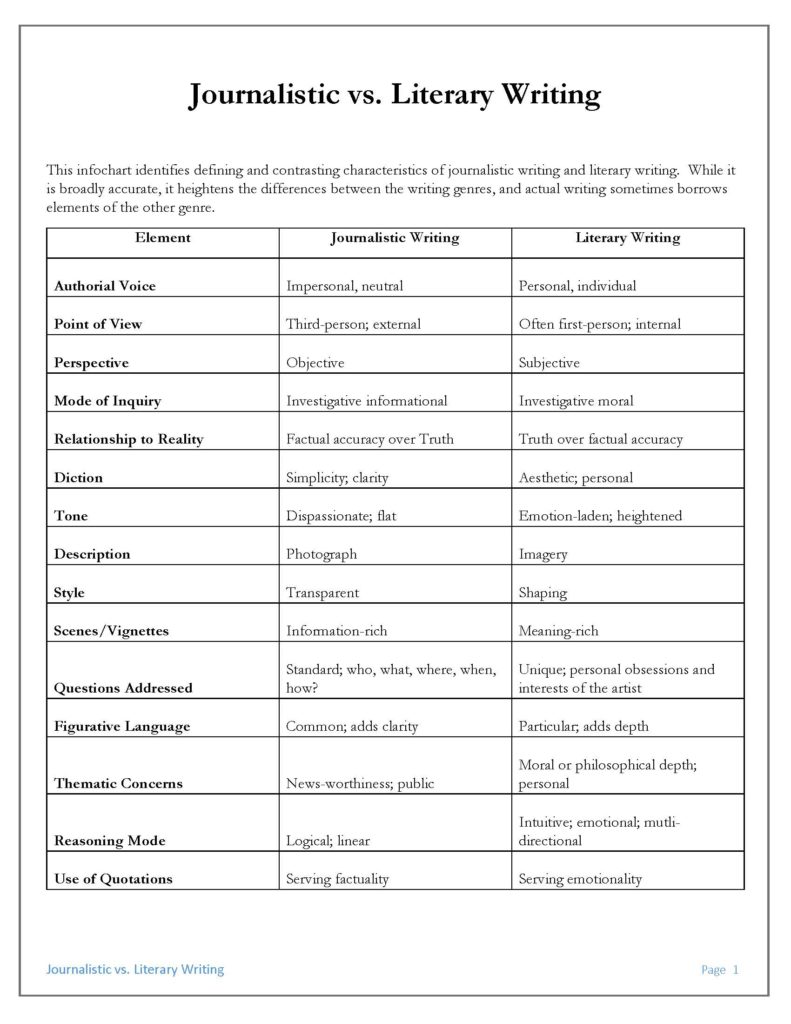

We established and taught through an analytic comparison between journalism and literary fiction, to begin with, on a stylistic and formalistic level.

Then we had students read carefully the selections of war journalism and a set of passages that we pulled from Half of a Yellow Sun that were most directly concerned with the fighting of the Nigerian Civil War, and its many consequences. We asked students to discuss these differences, answer a set of argument-based questions (at the end of the document with the war journalism) that asked for analytic comparisons of the techniques and stylistic devices in use in both genres, then had students write short analytic papers arguing for similarities and differences, as they perceive them, between war journalism and literary fiction about war.