ACCIS-ing Chess in a Critical Thinking Rich Classroom

This summer I have been working with high school chess coaches and players in Chicago, helping them apply their expertise in the game to their teaching and learning, respectively. This work is part of Argument-Centered Education’s Academic Competitions Classroom Infusion Series (ACCIS), outlined in a prior Debatifier post. This post is devoted to two of the larger set of resources that we developed together, applying the underlying academic components of chess to regular classroom teaching and learning in the core subjects, in a manner very parallel to the way that Argument-Centered Education has brought academic debate into regular classroom instruction by distilling the essential its components and infusing them throughout the school day.

Chess Symbolism in Film (English)

Overview

As students will learn from the YouTube channel Now You See It in its short video “The Meaning of Chess in Movies,” chess has a wide range of symbolic meanings in film. And it often has more than one meaning in the same movie. In this project students are going to take a closer look at the symbolic resonances that chess has in the 1993 film “Searching for Bobby Fischer,” based on the early life of a child star of chess, Joshua Waitzkin. Analyzing and understanding the symbolic meanings of chess in film can give us a more sensitive and nuanced reading of the way our culture understands and distills chess’s essential qualities. Students will use an argument-based, critical thinking centric approach to compare different positions on this debatable question:

What is the primary symbolic meaning of chess in “Searching for Bobby Fischer”?

When we talk about and analyze symbolic meaning in a film or literary text we ask what thematic ideas and suggestions an object or motif has in the work. In the grammar of fiction narrative and thematic meaning is infused into much more than what is literally said – said by characters, said by the narrator; meaning can found in setting, tone, figures, and in symbols. So, for example, when reading Herman Melville’s classic American novel Moby-Dick, an important question is what are the symbolic meanings of the white whale, Moby-Dick? Does the whale symbolize unavoidable fate? Ambition and the obsessiveness it can inspire? The meaninglessness and value-lessness of the universe?

Though the symbolic meaning of chess in films is multifarious and often complex, it should be possible to identify what among all of the possible meanings is the primary meaning of chess in “Searching for Bobby Fischer.” Selecting one of the symbolic meanings as primary will generally mean identifying the symbolic meaning of chess that is most central to the film’s thematic meaning. This is to say: the meaning of a symbol in a film or novel is integral to the thematic meaning of the work.

There are several possible symbolic meanings of chess in the film, and therefore several possible positions to take in our activity.

Chess represents dangerous, obsessive single-minded dedication to one pursuit, at the cost of a balanced, socially integrated life.

Chess represents a commitment to excellence, hard work, achievement, and distinction.

Chess represents pure, natural, innate genius and talent, and the way that genius and talent is randomly and unequally distributed throughout society.

Chess represents opportunity to change one’s life or one’s family for the better; it represents opportunity for betterment.

This list of symbolic meanings and interpretive positions may not be complete. If students have their own interpretation of the symbolic meaning of chess in “Searching for Bobby Fischer” that are distinct from these they can be added to the argumentation.

Procedure

(1)

Screen the short video “The Meaning of Chess in Movies,” from Now You See It. Prior to screening, ask students to note each of the different symbolic meanings that chess has in films, according to the video. Review and enumerate with students the symbolic meanings that they heard discussed in the video. Ask them if they have seen films or read books in which chess had any other symbolic meanings.

(2)

Introduce the debatable question:

What is the primary symbolic meaning of chess in “Searching for Bobby Fischer”?

Orient or refresh students on what we mean by symbolic meanings in films and literature, and how a single symbolic meaning can be argued to be “primary,” even when a symbol may have multiple symbolic meanings and resonances. Ask students to turn and talk to process their understanding, and ask students to share out highlights of these bilateral discussions.

(3)

Introduce and then screen three video excerpts from the film “Searching for Bobby Fischer.” Optional: repeat the screening of the Now You See It short video, to reinforce possible interpretive options. Cluster students into groups of three. Ask each group to identify at least two symbolic meanings of chess in the film. Have students share out these meanings and list them out on the board. Narrow down the list to viable interpretive positions, adding any of the four above that students did not already identify.

(4)

Distribute an argument builder with space for two arguments. Ask each student group to divide up the interpretive positions so that each student will be arguing for one of them. Then each student should build two arguments for their interpretive positions. You can model arguments here, but whether you model or not, you should circulate to support and guide students in their argument building. You should also showcase student examples that can be especially guiding.

(5)

When students have been given ample time to build their arguments, you are ready to begin the structured argumentation activity. You should moderate this activity based on these time parameters.

Opening Arguments 6 Minutes

Each student should spend about two minutes to state their two arguments (claims, supported by evidence and reasoning) for their interpretive position in response to the question about the symbolic meaning of chess.

Counter-Arguments 6 Minutes

Each student should respond with counter-arguments to the other two students’ arguments for their competing position. Try not to respond to counter-arguments, only to opening arguments during this portion of the structured argumentation activity.

Rebuttal Arguments 8 Minutes

This portion of the structured argument activity is a more open forum in which students should try to rebut the counter-arguments to their original arguments, and evaluate the competing argumentation in such a way that favors their interpretive position.

(6)

This activity can end with a round-table reporting on each group’s structured argumentation, in which a spokesperson summarizes the argumentation and clash, as well as what resolution or synthesis the discussion seemed to point toward – or whether the outcome was closer to a balanced continuation of a clash of interpretive ideas.

For purposes of assessment and accountability, students can submit the notes that they took during the activity, in addition to their argument builder. They can also, if you choose, write a short argumentative piece responding to the original debatable question.

Bobby Fischer vs. Magnus Carlsen (Social Studies)

Overview

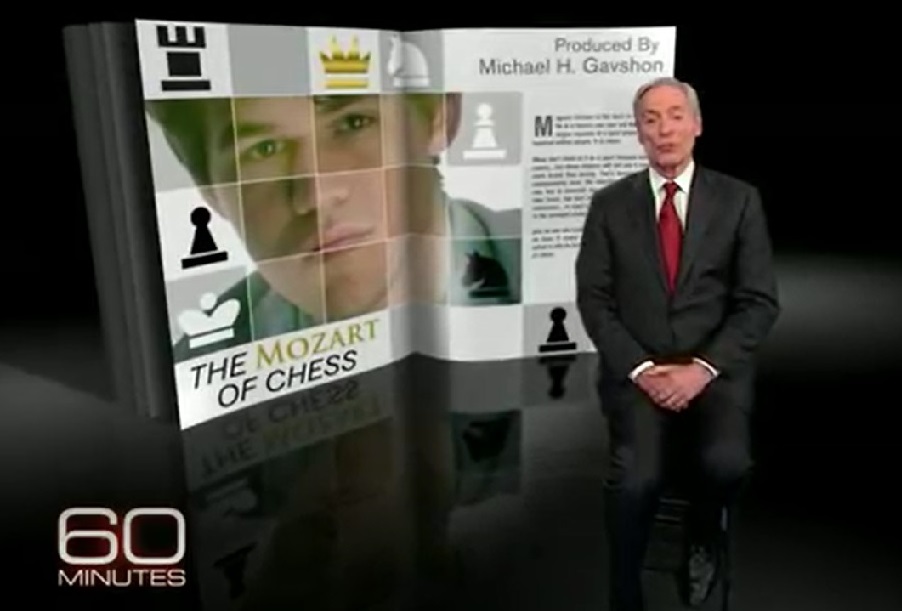

The Norwegian chess superstar Magnus Carlsen became the World Chess Champion in 2013, at the age of 22, and he holds this top position even today. He has captivated much more attention than the vast majority of other professional chess players have partly because of his charismatic genius; he has reached a peak rating, for instance, of 2882, which is the highest rating on record. But another reason for his stature is his having been a child prodigy, which seems to elicit especially strong reaction from a general audience. At 13 he defeated former World Champion Anatoly Kasparov, and at 19 he was the youngest chess player ever to have the highest FIDE rating in the world.

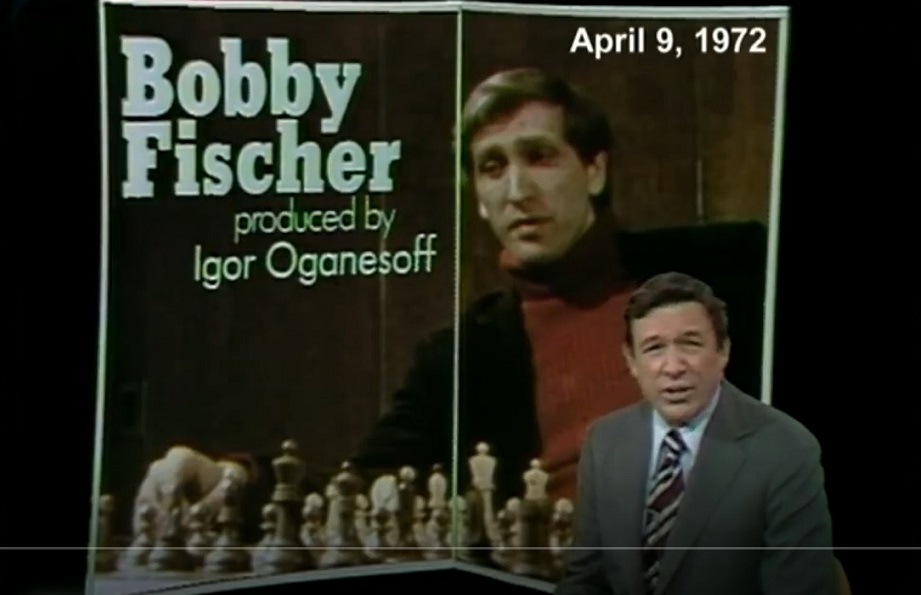

Chicago-born Bobby Fischer was also a child prodigy in the game of chess. He became the youngest United States chess champion of all time at the age of 14, in 1957. And a year later he became the youngest Grand Master in chess up to that time, at 15. In 1972, Bobby Fischer became the World Chess Champion by taking down a series of players from the dominant chess superpower, the Soviet Union, including Boris Spassky in “the Match of the Century,” held in Reykjavik, Iceland. His 2785 peak FIDE rating is certainly within close striking distance of Magnus Carlsen’s, and many close followers of chess and accomplished players have speculated about this question:

Who would win a chess match between Bobby Fischer (in his prime) and Magnus Carlsen?

In this activity, students will think critically about this question while they annotate videos and researched articles and then build and make arguments to support one position or the other.

Procedure

(1)

Introduce the debatable issue to students and provide a short orientation on these two chess Grand Masters, Bobby Fischer and Magnus Carlsen.

(2)

Distribute Video Annotators or have students make double entry journals (headed “Evidence from the Video” on one side and “Possible Claims” on the other side of the T-chart). Then screen the two short videos “Bobby Fischer on ’60 Minutes’” and “Magnus Carlsen on ’60 Minutes.’” The purpose of these videos is to enhance students background knowledge and contextual understanding of the two players’ careers, in addition to providing them support for possible arguments. Students should annotate both videos.

(3)

Assign students partners, or let them pick their own. They should decide themselves who will take the position that Fischer (in his prime) would beat Carlsen in a chess match, and who will take the opposing position. You will want to record the pairings and the positions of each student.

(4)

Distribute an argument builder with space for two arguments. Tell each student that they should build two arguments for their interpretive position. Students should research both chess players’ attributes and careers. One useful site is this Comparison of Top Chess Players Throughout History (which also has a citation list). You can also model arguments here, but whether you model or not, you should circulate to support and guide students in their argument building. You should also showcase student examples that can be especially guiding.

(5)

When students have been given ample time to build their arguments, you are ready to begin the structured argumentation activity. You should moderate this activity based on these time parameters.

Opening Arguments 3 Minutes per Side

Each student should spend about two minutes to state their two arguments (claims, supported by evidence and reasoning) for their interpretive position in response to the question about who would win in a match between Fischer and Carlsen.

Counter-Arguments 2 Minutes per Side

Each student should respond with counter-arguments to the other student’s arguments for their competing position. Try not to respond to counter-arguments, only to opening arguments during this portion of the structured argumentation activity.

Rebuttal Arguments 2 Minutes per Side

This portion of the structured argument activity is a more open forum in which students should try to rebut the counter-arguments to their original arguments.

Closing Arguments 3 Minutes per Side

In the closing arguments both students should evaluate the competing argumentation in such a way that favors their interpretive position.

(6)

This activity can end with a round-table reporting on each group’s structured argumentation, in which a spokesperson summarizes the argumentation and clash.

For purposes of assessment and accountability, students can submit the notes that they took during the activity, in addition to their argument builder. They can also, if you choose, write a short argumentative piece responding to the original debatable question.