Dismantling Racially-Motivated Arguments for Exclusion

Overview

Many times when we make arguments or we debate in the classroom we start with an open, debatable question on an issue central to a unit we are in, and then we read and study content in order to stake out a position on the issue and build evidence-based arguments that develop and support that position. This is a common sequence and method of academic argumentation in high school because it is prime preparation for the academic work you will do in college. There are plenty of other variations of argument-centered learning, though. In this project students will be carrying out one of them.

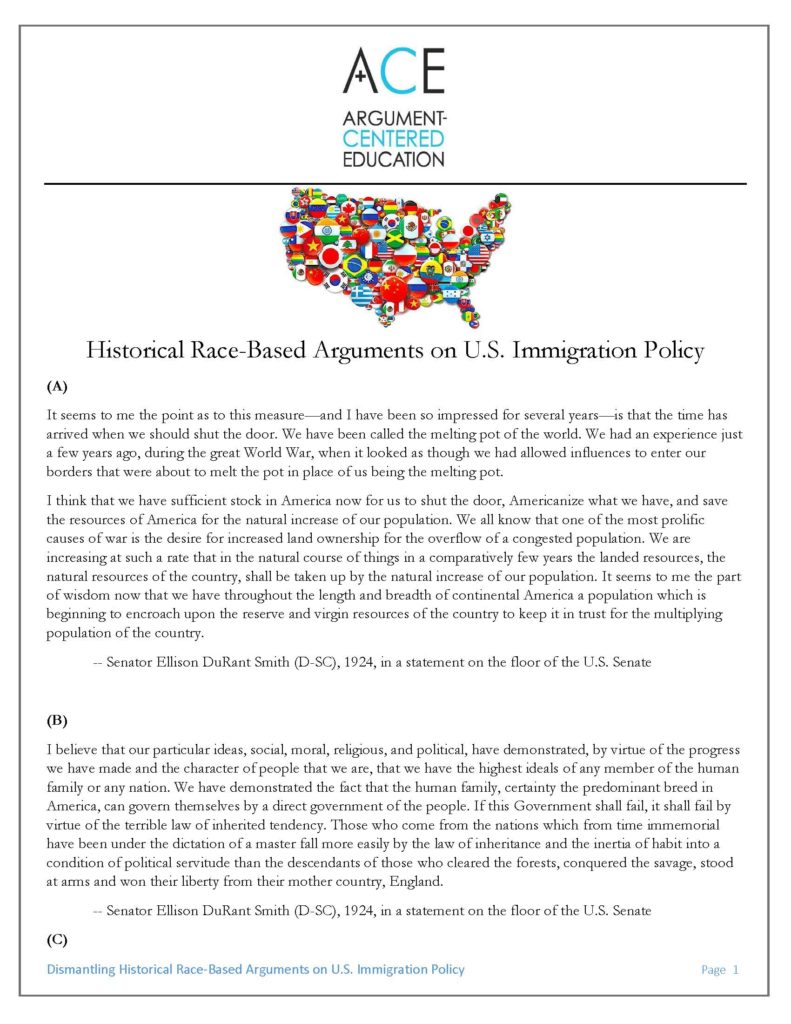

Our ability to make strong, convincing, well-reasoned arguments is the flip side of our ability to analyze and evaluate arguments insightfully, articulately, authoritatively. Being able to analyze and critique arguments is also socially, politically, civically empowering; when we can effectively analyze and critique an argument, we are in control of it more than it can be in control of us. Students in this project will be analyzing and critiquing historical arguments on United States immigration policy. These particular arguments are characteristic of their historical period, and, as students will see, they are rooted in racial bigotry. They also seem to disturbingly echo some of the arguments on immigration of our period.

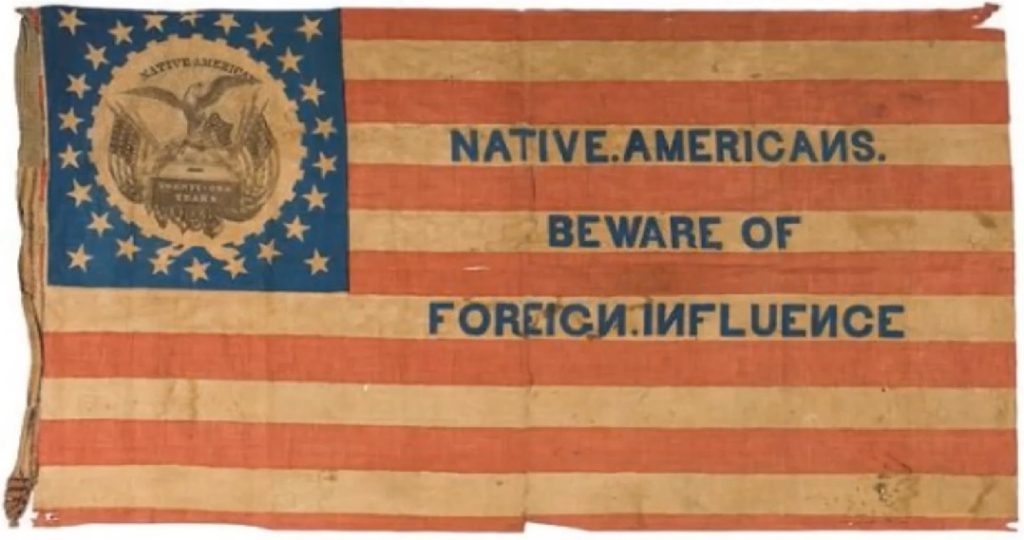

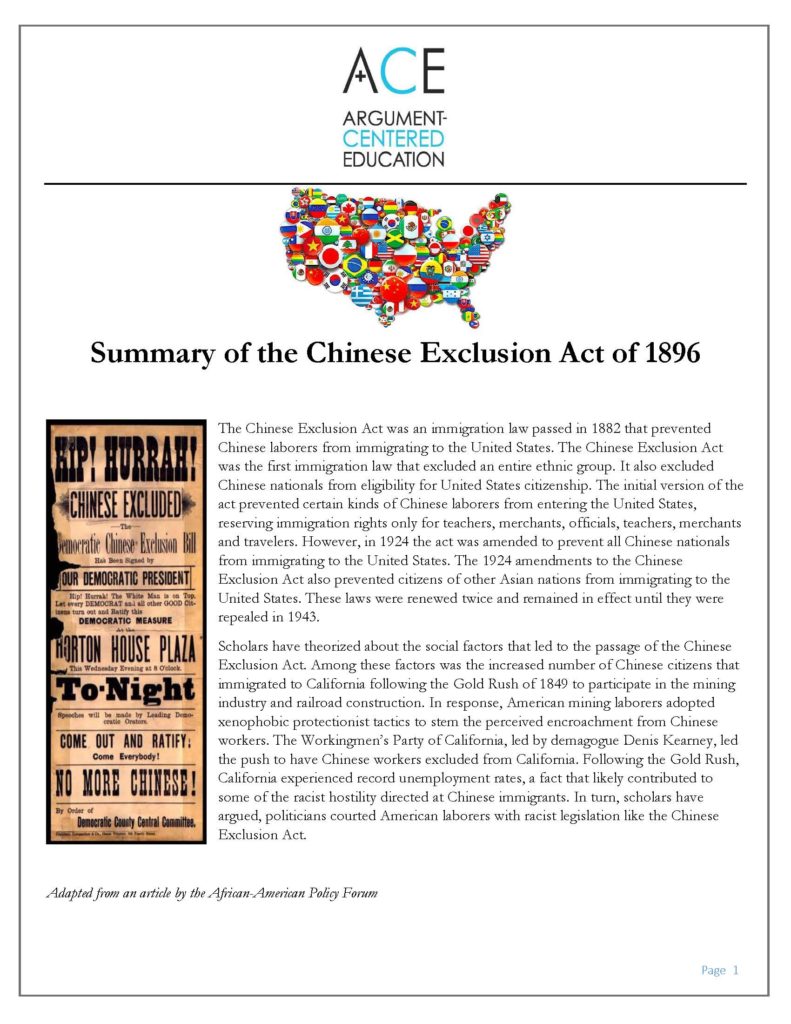

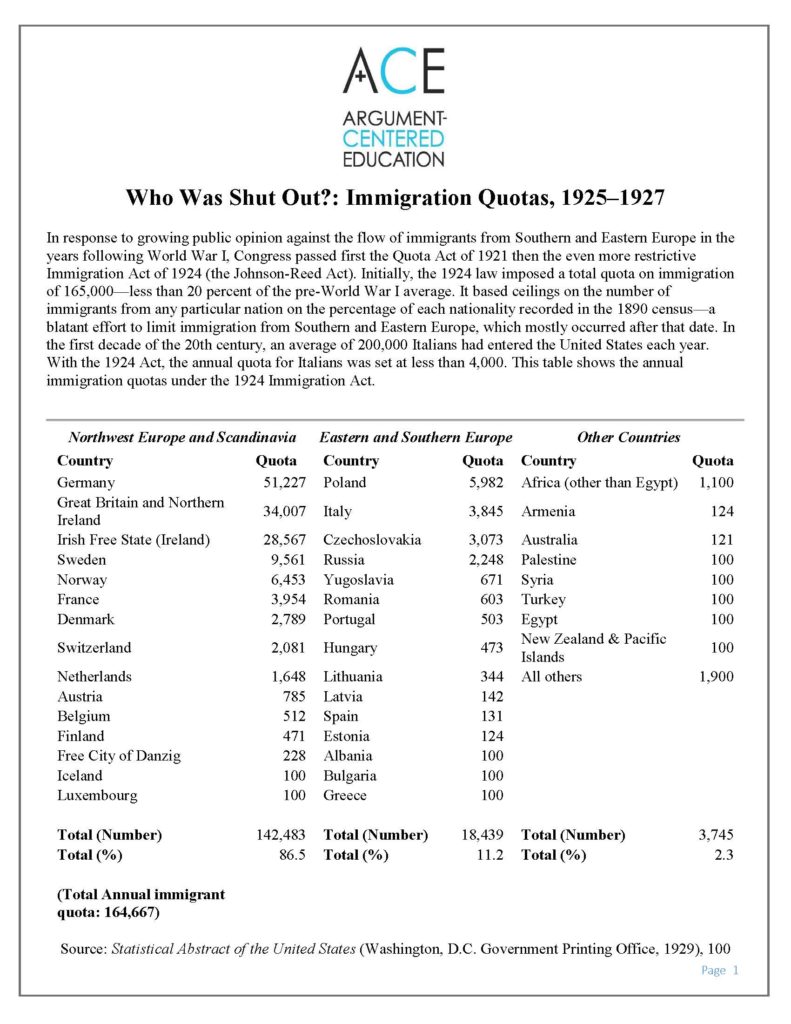

Asians, and in particular the Chinese, were the target of a great deal of racial prejudice and enmity during the mid 19th Century, establishing a pattern of anti-immigrant waves of political sentiment and immigrant scapegoating that persisted through the next century and into our own era. The first law in U.S. history to target a single ethnic or racial group for exclusion from this country was the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Anti-Chinese racism would show up in Justice Harlan’s famous dissent in the “separate but equal” Supreme Court case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). And then another, broader racially-tinged “nativist” movement resulted in immigration quotas based on race, ethnicity, and national origin were codified in the Immigration Act of 1924.

In Dismantling Racially-Motivated Arguments for Exclusion, Students will make a close and critical examination of characteristic arguments made for (or in) these historical artifacts, dismantling them for their racial motivation and invalidity as sound, evidence-based argumentation. And students will end with a look at a racially tinged argument on immigration policy within our present political moment, comparing it to the historical arguments we have critiqued.

Procedure

(1)

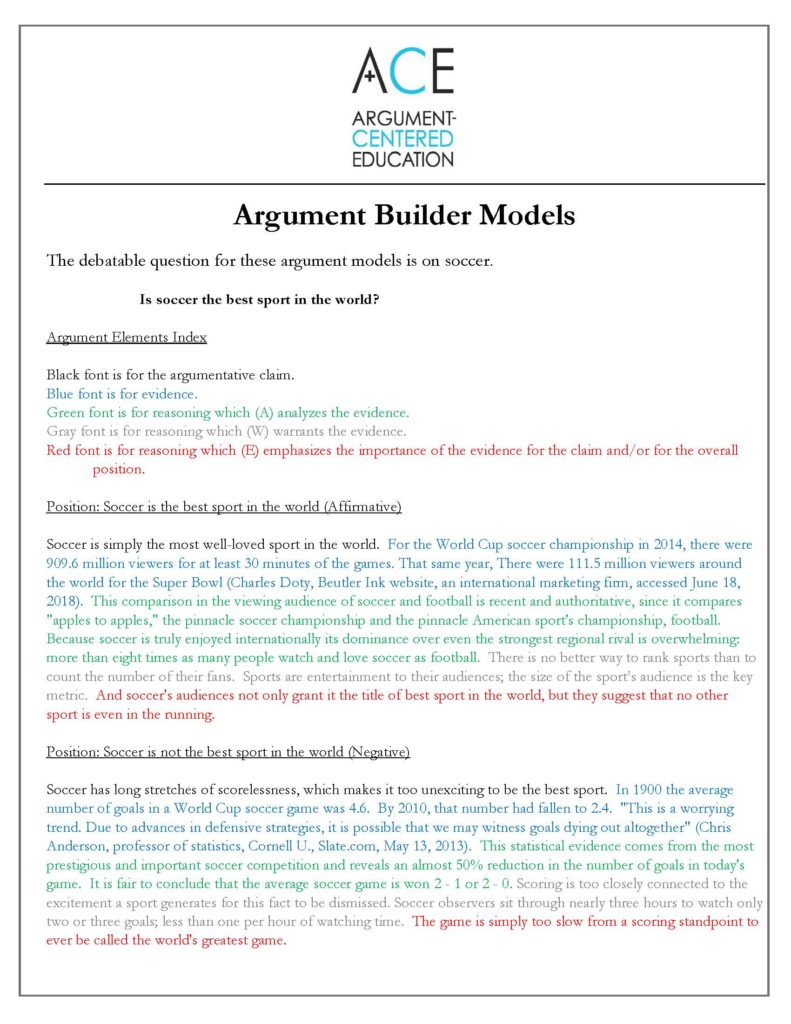

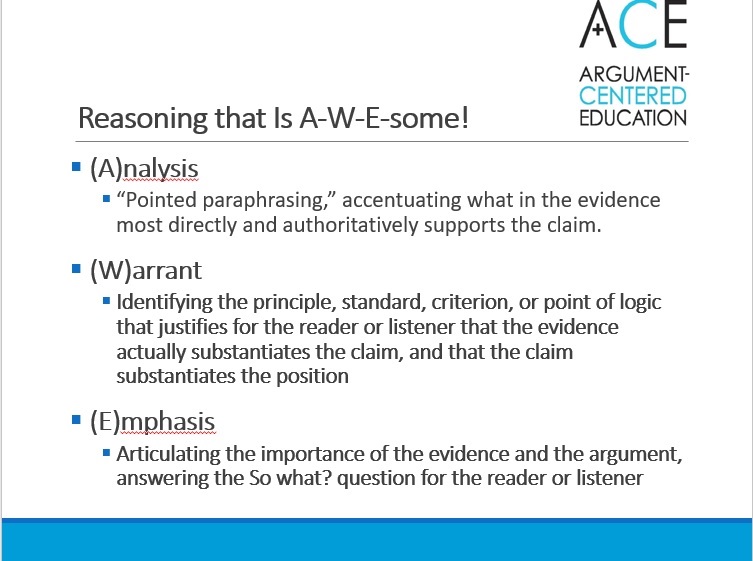

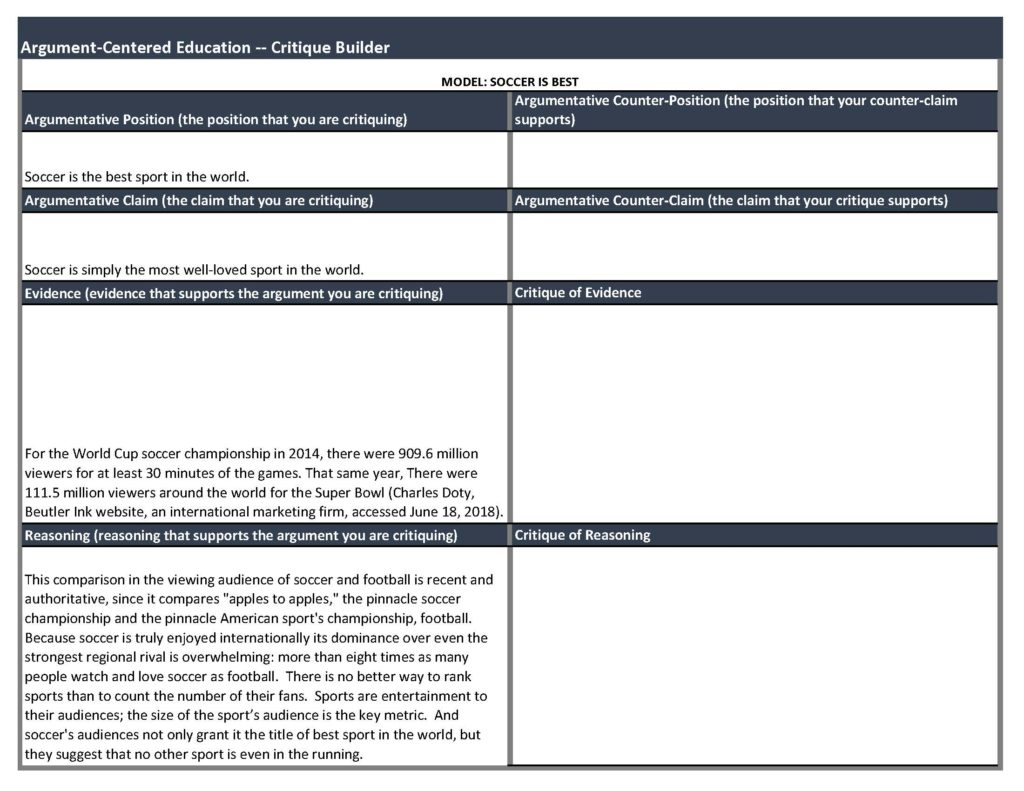

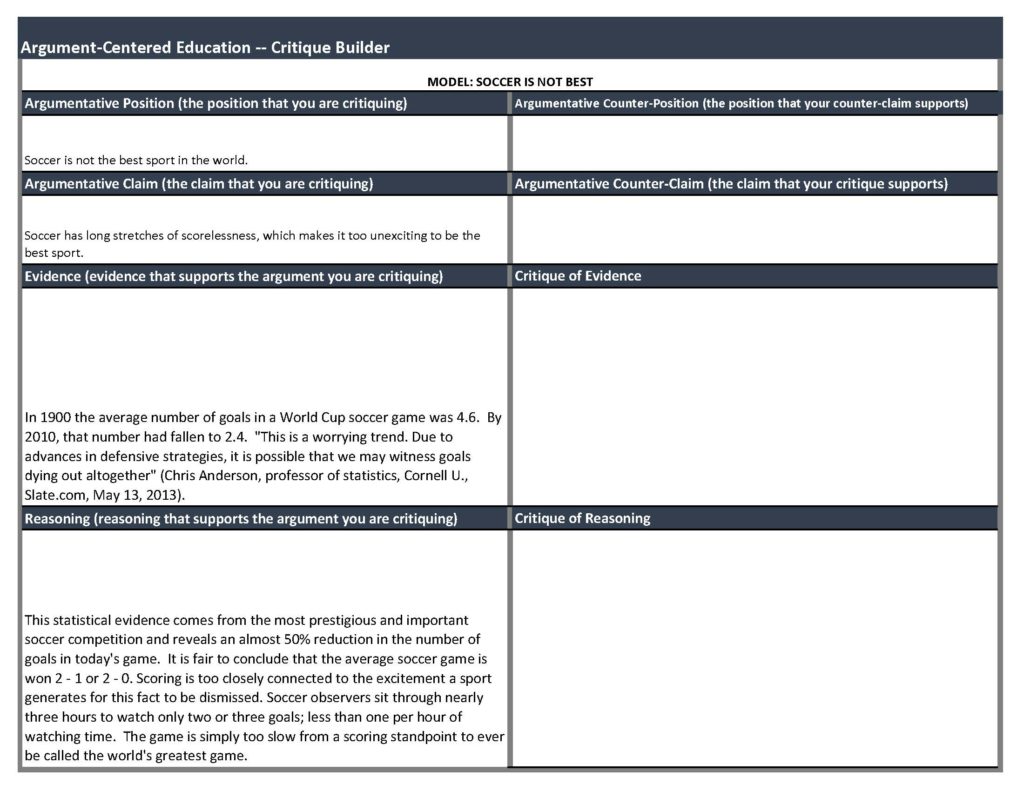

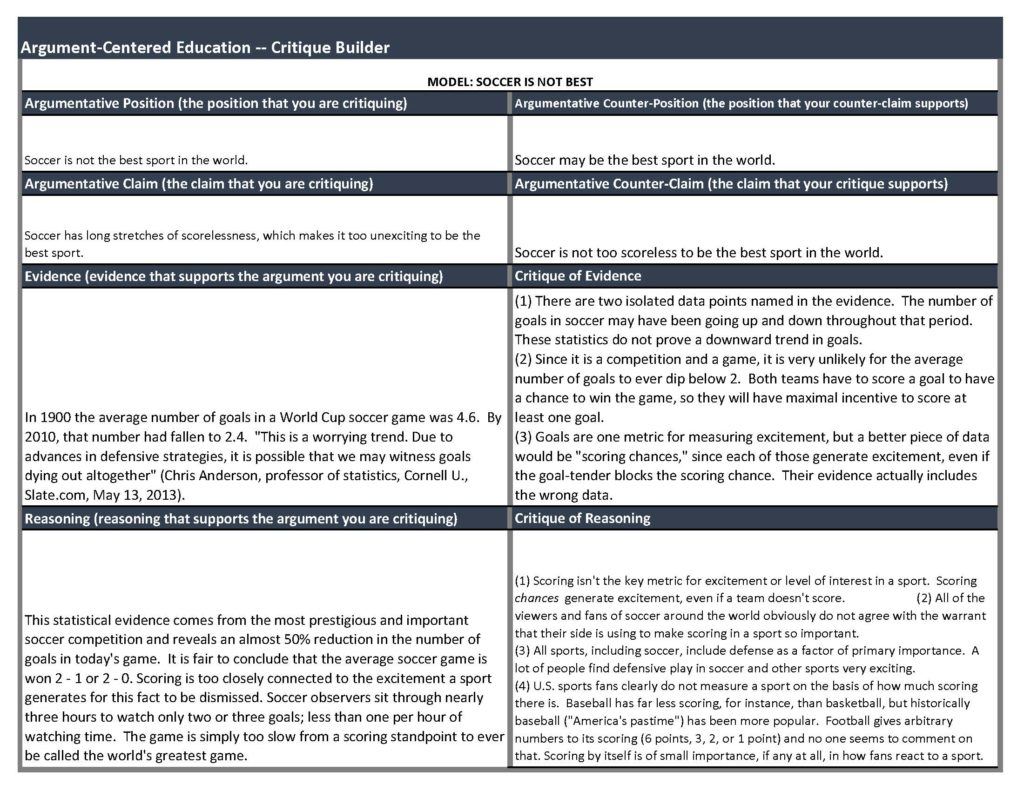

Students will read and discuss the argument models on both sides of the quasi-academic debatable issue, Is soccer the best sport in the world? Students will review the components of an argument: claim, evidence, and reasoning. And they will refresh themselves on the AWE-some system of disaggregating argumentative reasoning, into analyzing, warranting, and emphasizing the evidence as support for both the claim and the position being taken by the writer or speaker.

(2)

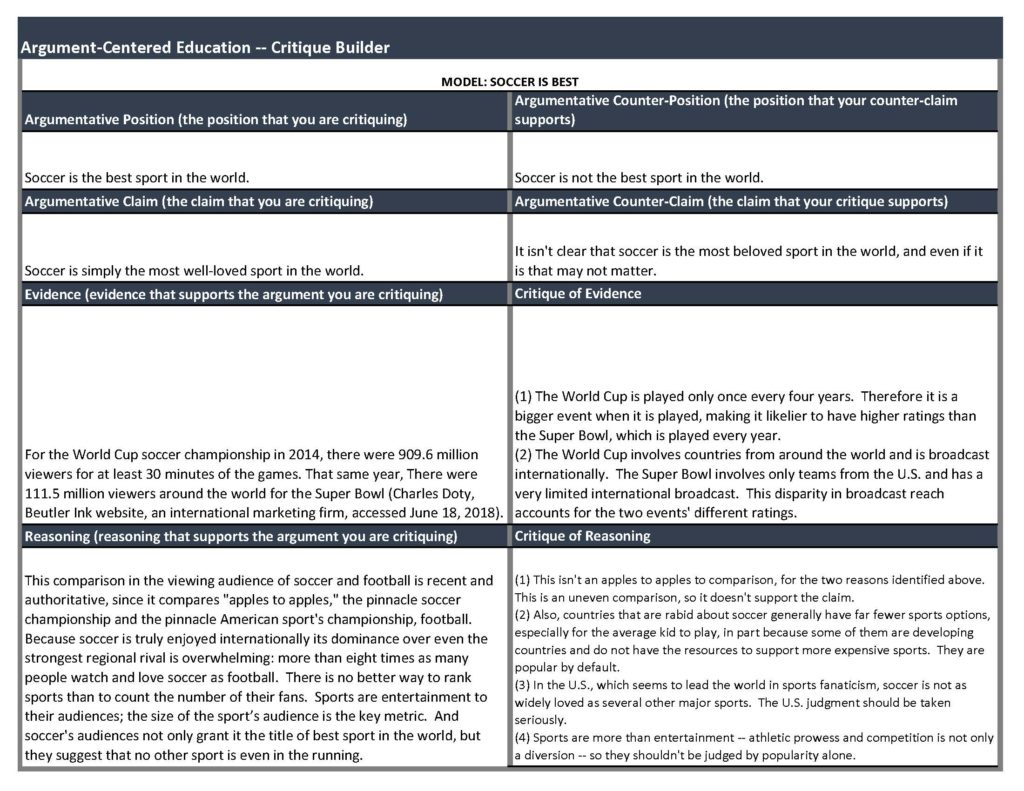

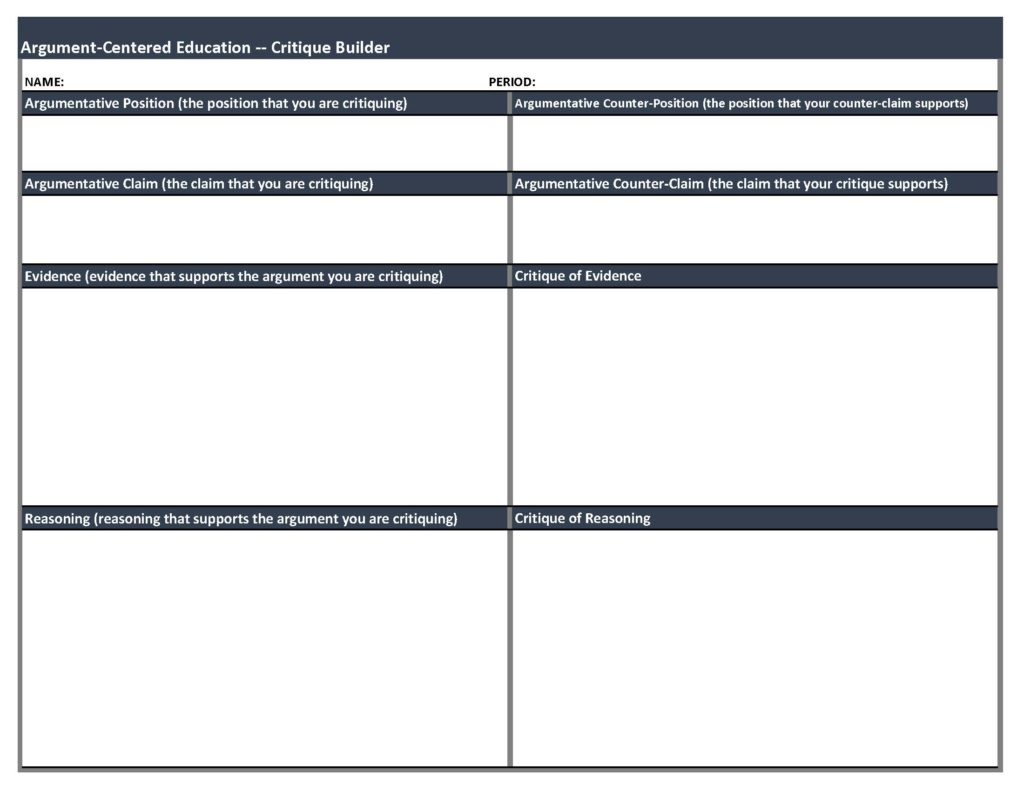

Students will compare the “partial” Critique Builder models to the soccer argument models, in order to understand how arguments are written into the Critique Builder and argument components are disaggregated. They will then have an opportunity to generate critique items for the right-side column of the Critique Builder. After they generate a list of critique items, discussing which are more and which are less supportable, reasoned, or valid, we will study a Critique Builder model. We will conduct turn-and-talk discussing in pairs from “I notice . . . . I wonder . . .” stems.

(3)

Each student will be assigned a partner for pairings that they will work in for the remainder of the project. Then, next, they will turn to background and context for the three historical artifacts that form the basis for this project on race-based arguments made to support and justify U.S. immigration policy. The class will screen three videos on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1924, and will have Q. and A. after each of them. The teacher will distribute the Notice/Learn/Wonder graphic organizer and we will do choral and silent reading of historical backgrounders on these artifacts, along with the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision of 1896.

(4)

Each pair will then be assigned two race-based arguments to analyze and critique. That analysis and critique will be conducted on two Critique Builders. The teacher will showcase student work that is especially exemplary and instructive.

(5)

In sharing out their work product, students will proceed down the list of race-based arguments made on U.S. immigration policy, covering as many of them as can in the time that the class has. When the teacher names an argument, she will ask which pairs critiqued it. One pair will then present their analysis of the argument – its claim, evidence, and reasoning – for the immigration position it supports, then they will present their critique of that argument. The other pair (or pairs) that critiqued that same argument should take careful notes because they will be asked to “critique the critique” – that is, very briefly summarize points on which the critiques agree, identify additional points that the critique had included that were valid, and attempt to refute or quality points in the critique that were not, in their view, valid.

(6)

The class will end with a screening of a recent statement by Fox News conservative commentator Laura Ingraham making an argument against immigration for the demographic changes that it has brought to the U.S. Students and teacher will do an informal analysis, critique, and dismantling of this argument, in a manner parallel to the way that did for the historical arguments.

(7)

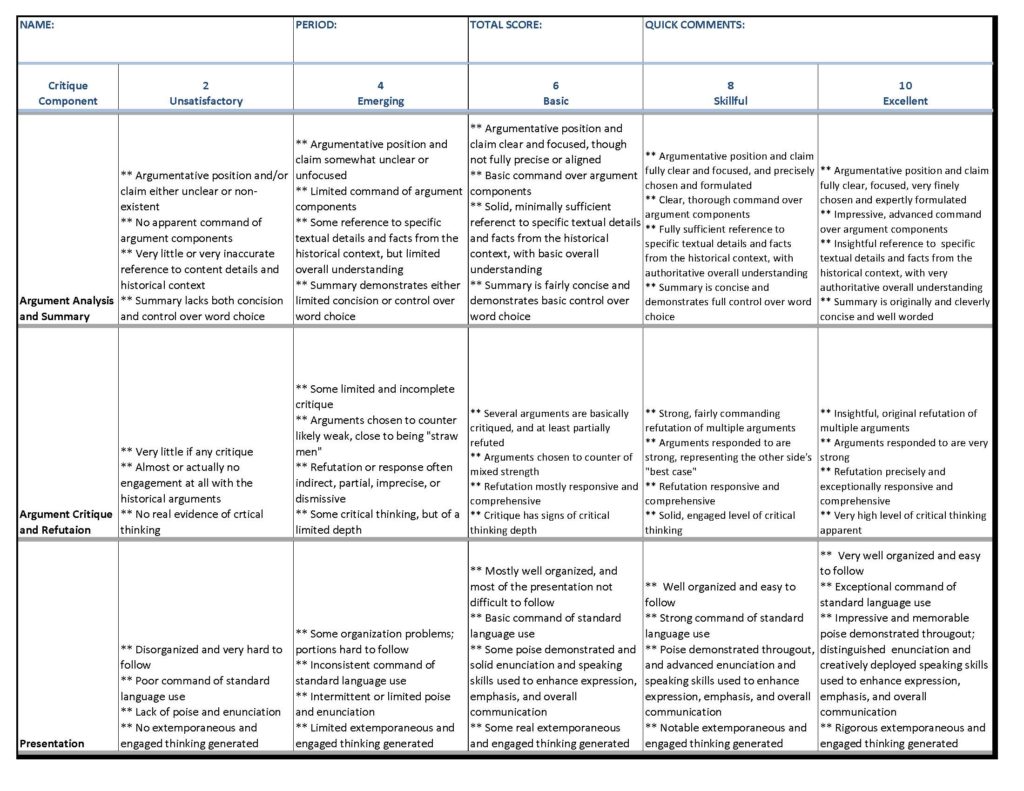

Students will turn in their Critique Builders. Each pair will be assessed using the Critique Builder/Presenter Assessment Rubric.