SPAR Debate: A Format for Rigorous, Real, Ready-to-Go Debating in Class

Overview

SPAR Debate is an excellent way to introduce students to debating in the classroom. It’s an activity for getting students initially exposed to debating, but also for isolating and introducing the key elements of academic argumentation.

SPAR is short for Spontaneous Argumentation debates. The term connotes, too, some of the jousting and practicing that we think of as “sparring.” SPAR Debate can be used with minimal research, and is therefore a very good format for getting students up and arguing. SPAR Debate can be used with academic issues, as a way to begin to immerse students in curricular content, or with non-academic (“fun”) issues, as a way to focus on debating format and individual argumentation skills.

Through SPAR Debate, students become more comfortable both with the activity of speaking in front of others and of learning about the defining features of academic argumentation. SPAR Debate can be used with “fun” topics, but can equally function as a format for more formal argumentation around issues central to the course curriculum, drawing on texts in use in the course. SPAR Debate can be used as an introduction to some of the concepts underlying argumentation and debate, or as a transition to content-specific argumentation activities.

Method and Procedure

(1)

Formulate an open, focused, balanced, authentic, and interesting debatable issue, based either the key contestable issues in the unit or on an immediately engaging non-academic topic.

(2)

If the debatable issue is based in the unit content, assemble readings, portions of texts being read in class, a Media List, or textual evidence selections. Use a direct instructional approach to teach this content, with reference to arguments that can be made on the issue.

If the debatable issue is non-academic, open with a short teacher-led discussion of the issue, asking students to formulate the viable positions on the issue.

(3)

Ask students to formulate two argumentative claims supporting each identified position on the issue. Then list out the claims on a document camera or on a white board. Combine any claims that are closely similar, and working with students refine the formulation of claims as needed. Discuss with the class which are the most supportable claims, though don’t dive deeply into the evidence and reasoning for any of the arguments, at this stage.

(4)

Pair students into two-person partnerships, and assign each team a side. This assignment can either be arbitrarily determined, or it can attempt to reflect student preference. The viability of including student preference depends a lot on whether the issue is one with an approximately equal number of students on each side. If the issue is based in unit content, student preference should usually be less of a consideration: students should be academically trained to make arguments on any side of a balanced academic controversy.

(5)

Each two-person team should decide on their speaker positions: first affirmative (1A) and second affirmative (2A), and first negative (1N) and second negative (2N).

An alternative structure is to put students into groups of four, and have students decide on these speaker positions, for each side: Case, Cross-Examination, Counter-Arguments, and Closing Statement. Either structure works. The two-person structure gives each student more speaking time, but can take longer to implement, since there are twice as many debates taking place.

In the two-person structure, each team divides speeches this way:

1A — Affirmative Case and Affirmative Closing Statement

2A — Affirmative Counter-Arguments and Cross-Examination

1N — Negative Case and Negative Closing Statement

2N — Negative Counter-Arguments and Cross-Examination

(6)

Each team’s case should consist of two or three arguments. The arguments should be drawn from the claims that you listed out (combined, reformulated) in the Step 3 above. You can let teams decide on the number (two or three), or you can determine that number for this implementation of SPAR Debate. Each argument should of course be distinct from the other, and each should be supported by backing, in the form of factual or textual evidence; examples, history, or data; and analytical and logical reasoning.

You can either have students develop their backing using their own formatting, or you can distribute Argument-Centered Education Argument Builders and they can use these graphic organizers to build their arguments.

(7)

Each team’s counter-arguments should be a rebuttal of the other team’s case – i.e., a point-by-point refutation of their two or three arguments.

Each team should be building at least one counter-argument against each of the claims listed out for the position that they are opposing. They can formulate these counter-arguments using their own format, or an ACE Counter-Argument Builder graphic organizer.

(8)

The closing statement should be an evaluation of the competing arguments in a manner that puts all of the arguments in the debate together, favoring the speaker’s side. The speaker should extend one or two of the strongest arguments from their case, with a final rebuttal and mitigation of their opponent’s arguments, concise and synthesized.

This, anyway, is the ideal purpose of the closing statement. Students less experienced with academic debate will often attempt to respond to and rebut the counter-arguments and not do much more.

(9)

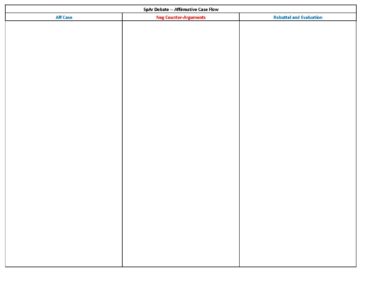

You should take careful notes of all the speeches on the SPAR Debate flow sheets, on a projector or document camera, so that the arguments can be tracked, and students’ refutation and argument evaluation can draw on this record. Argument tracking – in competitive debate, this is called “flowing” – is crucial to enforcing refutation, which is the locus of critical thinking in academic debate and argumentation.

(10)

The SPAR Debate speech format:

Affirmative Case — 3 minutes

Cross-Examination of the Affirmative – 1.5 minutesNegative Case — 3 minutes

Cross-Examination of the Negative – 1.5 minutes

Negative Counter-Arguments — 2 minutes

Affirmative Counter-Arguments — 2 minutes

Negative Closing Statement – 2 minutes

Affirmative Closing Statement – 2 minutes

One suggested method is to conduct one round of simultaneous SPAR Debates, with every team debating against another team, simultaneously. You will have two roles: (a) most importantly, keep careful and authoritative speech time, announcing the beginning and ending of each speech, and (b) circulate to ensure that teams are debating on task and giving affirmation and direction, as appropriate. You can select one of the debates to be showcased in a second round, in front of the full class. This SPAR Debate you should track on a flow sheet screened by projector or document camera for the class.

The students can vote for the winner after the showcase debate. They should be told to vote exclusively on the arguments and evidence presented in the debate round. A productive analytic discussion can follow the showcased debate.

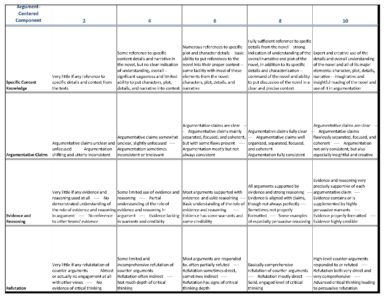

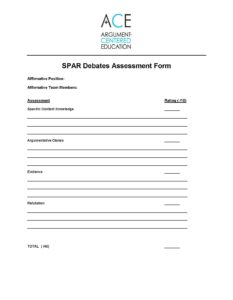

Assessment

Each student can be assessed through a combination of the submission of their group’s argument and counter-argument builders, and the speaking that you hear them perform. In most instances where teams are two-person, the division of speeches provides each speaker the opportunity to demonstrate each of the five central components of curricular debate.

Additional Considerations

* You can analyze and critique speeches with isolated academic argumentation component criteria in mind. For example, you can isolate the responsiveness of each speaker in the rebuttals and closing statements. Or you can isolate the use of evidence or argumentation principles in the cases.

* At or near its beginning, each side’s case (affirmative and negative) should include the issue statement, and whether the speaker is affirming or negating it.

* Each speaker should begin identifying him- or herself, too.

* Each argument in the case should include at least one piece of evidence – some objective fact, example, piece of data, or reference to text. If texts are being used to form the basis of the debates, each argument should either quote or paraphrase at least one piece of textual evidence.

* The flow sheet is an essential mechanism for enforcing refutation. The flow sheet records all of the arguments in the debate and reveals whether each argument has been refuted (or at least whether an attempt has been made to refute it) or conceded. So your flowing the showcase debate is a must, at a minimum.

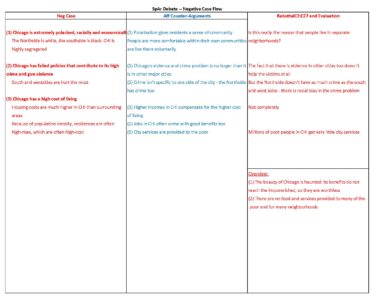

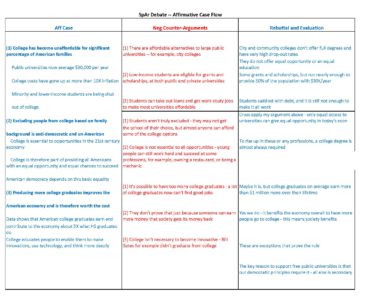

* There is one SPAR Debate flow sheet for each case (affirmative and negative), and the layout of each flow sheet corresponds with the refutational burdens of each speech after the two cases.

Models

We’ve produced several models for use in implementing SPAR Debate in your classroom, specifically flow sheets from model, in many ways idealized SPAR Debates, and two model Argument Builders completed in alignment with the second of the two model debates.

The first SPAR Debate flow sheet model is on this debatable issue:

Is Chicago a desirable place to live?

The other model SPAR Debate we produced is on this issue:

Should American public colleges be free?

A closer analysis of this SPAR Debate model on free public college will be taken up in a future Debatifier post, but in the meantime here are the arguments that each side opens with.

The affirmative’s opening (case) arguments:

1. College has become unaffordable for a significant percentage of Americans.

2. Excluding people from college based on family background is anti-democratic and un-American.

3. Producing more college graduates improves the economy and is therefore worth the cost.

And the negative’s:

1. Free public college is completely unaffordable for our society.

2. The free system would be gamed and abused.

3. University education would no longer be worth much.

These arguments were built in our model SPAR Debate on these ACE organizers.

With this cache of argument-centered instructional resources, any teacher in any discipline is well equipped to implement SPAR Debate in their classrooms — today, tomorrow, next week, or next unit.