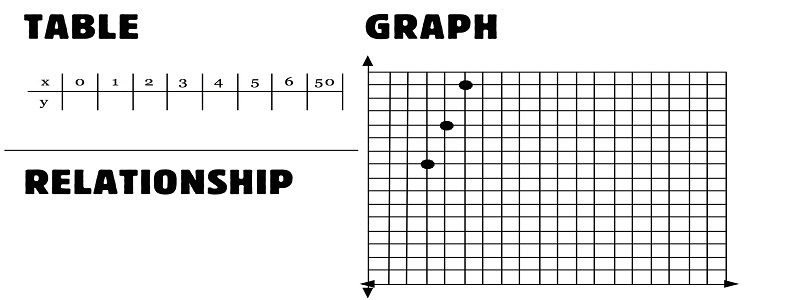

Arguing Math: Justify and Critique Solutions to Algebraic Relationships in Two Variables

Current standards in mathematics require that students be able to “construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others” (Common Core Standards, Standards of Math Practice 3). Further, “mathematically proficient students . . . justify their conclusions, communicate them to others, and respond to the arguments of others.” This activity has students justifying and making arguments for their solutions to higher-order thinking math questions, and it has students questioning or critiquing the solutions of their classmates.

Website (Re)Construction Project

One of Argument-Centered Education’s partner schools is implementing a highly innovative piece of curriculum in its U.S. History classes.

Called the Website (Re)Construction Project, it has students create argument-based web pages, on the course’s website, about an issue related to the Reconstruction period or the Civil War. Student web pages take a position on the debatable issue formulated specifically for the topic that they choose (or students can formulate, for instructor approval, their own commensurate debatable issue). Their designed webpages support that position with 2 – 4 evidence-based arguments. Evidence is required to come from a blend of primary and secondary sources, with weighting going to the primary. Each student’s webpages must also address and refute at least one strong counter-argument. Students are encouraged to use historical photographs, newspaper and personal accounts of the period, and other artifacts to create a visual theme on their webpages, one that “rhymes with” their argumentative position.

Organizing a Unit by Debatable Issues: ‘Number the Stars’ and a Curricular Organizer

Fundamental to coherently argumentalizing literacy curriculum is solving this puzzle: how will debatable issues or essential questions actually and effectively organize all aspects of a unit, including content delivery, discussion, performance tasks, and assessment. There are many means to building in this coherence to unit planning and implementation, of course. What’s important is to use tools that are applicable to the dimensions and resources specific to the unit and its curricular approach, but that also fulfill the generalized purpose of tying all elements of a unit, whether loosely or tightly, back into its driving arguable questions.

‘The Great Gatsby’ and Assessing Student Argumentation

Beatrice exceeds her [cousin] as much in beauty as the first of May doth the last of December.

— Much Ado About Nothing, I.i.185-187

Shakespeare was more than a little in love with the month of May, in Much Ado and elsewhere. Teachers, not so much — despite the narrowing chasm that the month portends to summer and its mostly more relaxed rhythms. The reason for teachers’ coolness toward the “Rose of May” (Hamlet, IV.5.133) can be named in a single word: assessment. May is testing season, and with that comes a flurry of misgivings, about misuse, overuse, curricular de-railment, unwarranted and discouraging final verdicts.

Argument Pedagogy and the Boomerang Effect, Part 1

By Dr. Gordon Mitchell

Ideal models of argumentation invite us to envision a world populated by arguers who gather evidence, test the strength of the evidence, and then carefully infer warranted conclusions based on that evidence. Of course, no one is perfect, so mistakes can be expected and fallacies are bound to occur in practice. But social psychology research suggests that everyday patterns of argumentation do not just deviate from such ideal norms; they tend to invert them. This inversion occurs when arguers begin with anchored conclusions and then proceed to seek confirmatory evidence in support of those conclusions, often subconsciously ignoring or discounting contrary evidence along the way.