Argument Pedagogy and the Boomerang Effect, Part 1

By Dr. Gordon Mitchell

Ideal models of argumentation invite us to envision a world populated by arguers who gather evidence, test the strength of the evidence, and then carefully infer warranted conclusions based on that evidence. Of course, no one is perfect, so mistakes can be expected and fallacies are bound to occur in practice. But social psychology research suggests that everyday patterns of argumentation do not just deviate from such ideal norms; they tend to invert them. This inversion occurs when arguers begin with anchored conclusions and then proceed to seek confirmatory evidence in support of those conclusions, often subconsciously ignoring or discounting contrary evidence along the way.

Joining the Conversation: Making a Space for Choices and Voices

By Patti Minegishi Delacruz

Those who have taught each grade level of high school will argue for a favorite – and perhaps least favorite – age group to teach. Five years ago, I would have claimed that sophomores are the most challenging group; this age group is arguably at one of the most difficult developmental junctures of their lives. However, this also makes them the most fearless and formative creators of arguments.

Over the years, I have observed how our “Joining the Conversation” unit is the most empowering unit of study for my sophomores in intermediate English, a course that serves a wide and unique range of skill-levels and social identities. This unit focuses on engaging students in argumentative thinking through accessing burgeoning opinions on timely issues, listening carefully to real voices speak on real problems, and developing own argumentative voices through verbal discussions and written products for an audience.

E-Books on Art Arguments: Bringing Together Art as a Theory of Knowledge, Digital Learning, and Argumentation

By Vickki Willis

As an International Baccalaureate Theory of Knowledge instructor, my goal is to provide students with not only a deeper understanding of the branches of liberal arts learning, but also with real world learning experiences that they can use past high school and moving into college and the workplace.

The objective with my unit on “E-Books on Art Arguments” is to give students a new creative outlet and skill set: digital design. The concept of E-Books is not new; however, it may be new to your students. I used it as a digital learning tool to develop their understanding and appreciation of art, and the controversies and academic arguments that have arisen around several of the most famous and accomplished European and North American artists of the past 100 years.

Document-Based Argumentation and International Response to Genocide

Document-based questions (DBQs) have become an increasingly popular way to teach history and social science in American middle and high schools. The activity starts with a debatable issue, then students are given a set of short excerpts from primary documents related to the issue. Students use the thinking tools of historians as they build arguments to support a position on the issue. Sounds — and is — pretty argument-based.

Argument-Centered Education’s variation on document-based questions — which we call document-based argumentation (DBA) — brings to the fore the argument construction process (making it explicit that that’s what historians, and therefore history students, are doing in academic situations like these), brings argumentation into a consistent system for teaching argument, and (crucially) introducing a component that requires refutation (the locus of critical thinking in argument) and debatificaction.

“Hamilton: An American Musical” and the Politics of History

Our Federalist v. Antifederalist project incorporates several clips from MacArthur “Genius” Award winner Lin-Manuel Miranda’s super-successful current play “Hamilton: An American Musical.” Miranda’s work — as most everyone probably knows by now, given how much attention it has received, from the academy, the theater, the music industry, the education sector, the media, even the White House — sets a drama based on the biography of America’s founding Treasury Secretary and the figure on the ten dollar bill, Alexander Hamilton, to hip-hop music and lyrics. Millions now — and not least, thousands of middle and high school students — have responded with great enthusiasm to this “story of American then, told by America now,” as the show’s clever marketing slogan has it.

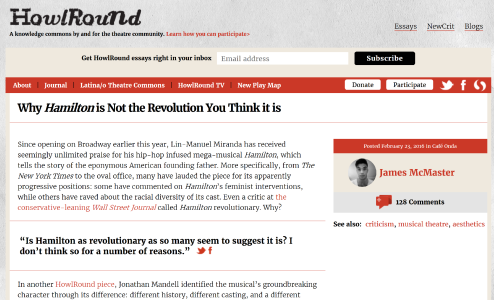

Though “Hamilton: An American Musical” has been wildly successful, a rather sturdy critique has recently surfaced, one which presents a kind of an argument-centered offshoot opportunity to our Federalist v. Antifederalist project. Dissenters have emerged trying to hammer holes in the wall of praise the show has received. They are making some arguments that fall squarely within the realm of academic discourse, within disciplines such as history, social science, historiography, drama, music, and aesthetics. I could envision a robust week or two-week high school project that teaches and has students debating the incipient controversy over the politics of “Hamilton.

For sources of the critique, Rebecca Onion in Slate has many or most of the references in a current post —

He develops these claims:

1. “Hamilton” is sexist — or at least notably non-feminist — with lines and lyrics for female characters that are almost all about men (especially Hamilton) and the projects and activities of the “founding fathers.

2. “Hamilton” propounds a “bootstraps immigration” narrative that implies that Alexander Hamilton’s success from his humble background was solely due to his “working a lot harder . . . being a lot smarter . . . being a self-starter,” and ignoring structural inequalities and a system of subjugation that enforced racial and class barriers.

3. “Hamilton”‘s minority casting is a “misplaced revolution” that has actors of color portray what remains a white narrative, and one that leaves out the actual role (even though it was a subordinated, oppressed one) of people of color, including slaves, of the American Revolutionary period.

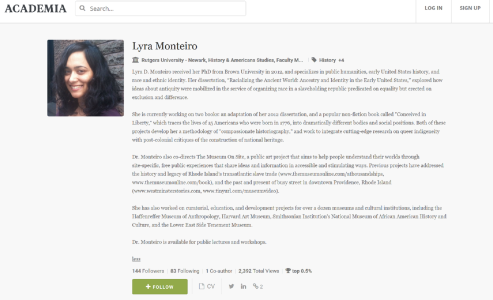

Then there’s Lyra Monteiro, a professor of history and American studies at Rutgers University, who published a rather powerful critique in The Public Historian in February —

The musical undoubtedly does have a special impact on this [a high school student] audience. Seth Andrew, the founder of Democracy Prep Public Schools [in New York City] took 120 students to see the show and reported, “It was unquestionably the most profound impact that I’ve ever seen on a student body.” And Miranda has noted that young people “come alive in their heads” when they’re watching the show. If the goal is to make them excited about theater, music, and live performance, great. But reviews of the show regularly imply that what is powerful about the show is how it brings history to life. So I ask again: Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with — one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?

For sources praising the play, one only needs to know where to find Google.com, but the Onion post above has links to supporters of it, and closely reading the hip-hop lines of the play themselves might supply the most convincing evidence to be analyzed by students in its favor.

The debatable issue might simply and directly be:

Is “Hamilton: An American Musical” a revolutionary piece of musical theater?OrDoes “Hamilton: An American Musical” function to democratize the teaching of the American Revolutionary period of U.S. history?