Argument-Centered Content Delivery

Overview

Posters have gone out to schools and districts near and far identifying the five universal steps to argumentalzing instruction — though some posters remain, if you haven’t gotten yours. Previous articles in The Debatifier have (in parts 1 and 2) described criteria and analyzed the process for effectively formulating a debatable issue: the first step in the five-step argumentalization process.

It’s time to take a closer look at the second step to argumentalizing instruction: teaching content through arguments. Students’ obtaining content knowledge and understanding is not only required to meet specific academic objectives across disciplines, it is also (as we see time and again) essential to their ability to make convincing, college-directed academic arguments.

The Argument-Based Socratic Seminar

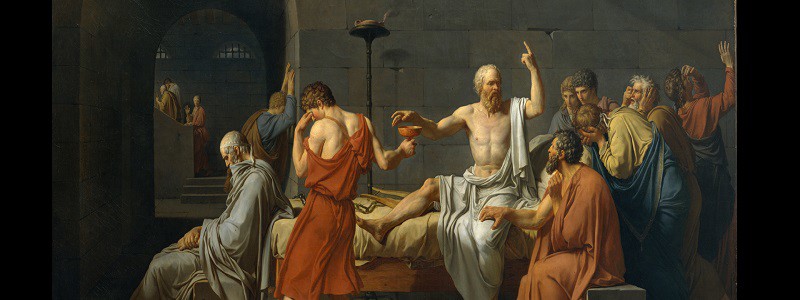

Named for Socrates (469 – 399 B.C.E.), one of the founders of Western philosophy, the Socratic Seminar is a formalized classroom discussion activity that emphasizes reflective thinking about big questions and the use of evidence to support responses. According to Elfie Israel, in Inquiry and the Literary Text (NCTE, 2002):

The Socratic seminar is a formal discussion, based on a text, in which the leader asks open-ended questions. Within the context of the discussion, students listen closely to the comments of others, thinking critically for themselves, and articulate their own thoughts and their responses to the thoughts of others. They learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and civilly.

The Five Steps to Argumentalizing Instruction

One of the signature features of the services model developed and employed by Argument-Centered Education is its embeddedness. Not only is its teacher coaching embedded within schools and active classrooms, so that teachers get observation-based feedback and targeted modeling support, but its curriculum design and adaptation works from curriculum that its partner schools and teachers are currently working with and to which they are committed. Instead of importing argument-based curriculum from outside, we work to build argumentation from the inside of an individual teacher’s, or department’s, or school’s, or district’s in-place instructional content and methodology.

External curricular components can often feel like diversions from the trajectory of a course. They can be and often are tried a couple times then quietly dropped. They can generate understandable even unspoken resistance from educators who entered the profession in part because they have an intellectual passion for certain fields of learning, things they know, and have dedicated their professional lives to sharing with the next generations. And they can impair the effectiveness of an on-going and embedded professional development strategy because they restrict demonstration of the use of argumentation to an external curriculum.