Athens vs. Sparta: An Argument-Based Project, with Documents, Debates, and Discussion

Overview

Ancient Greece is often considered the birthplace of Western Civilization. When we study the place and time of ancient Greece — in, for example, Humanities, World Studies, European History, Civics, or Government — we are studying seminal antecedents of the United States — social, cultural, educational, political. One angle in this content is to contrast the primary city-states, and Peloponnesian War antagonists, Athens and Sparta.

This multi-layered argument-based project has students study the two city-states through five domains of these comparable but contrasting societies: economy, education, government, military, and treatment of women & slaves. Students engage in close examination of primary and secondary documents, extensive written and oral discussion of the arguments in these documents, and Table Debates (with an argumentative writing component).

Information Clustering & Understanding Photosynthesis

Overview

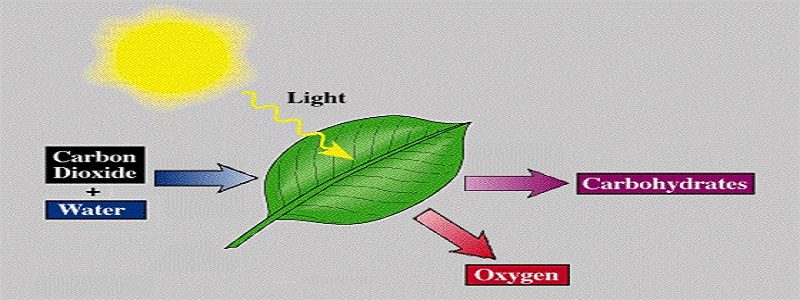

Photosynthesis is one of the most essential natural processes studied in biology. Students can understand very little about plants, trees, vegetation, and crops without understanding the process by which they convert sunlight and its energy, in combination with carbon dioxide and water, into carbohydrates and oxygen (and a bit of gaseous water).

This activity builds students’ understanding of the process of photosynthesis by having them cluster information about the process of photosynthesis, having them critique other students’ information clustering, and then finally having them respond to other students’ critiques.

Building Them Up, Knocking Them Down: Argument and ‘Elizabeth’s Jamestown Diaries’

Overview

Patricia Hermes’ children’s historical fiction Elizabeth’s Jamestown Colony Diary: The Starving Time, Book 2 (Scholastic Inc., 2001) takes an up-close look at the original Jamestown colony settlement of the English London Company in what is now Virginia, in North America. The work is narrated by a precocious 9 year old girl named Elizabeth. She is drawn as a typical girl, if especially verbal, but she is witness to an extraordinary historical place and time.

The second book of this two-part fictionalized diary account of the Jamestown settlement, The Starving Time is set in 1609 – 1610, and focuses in particular on the awful winter in the middle of this period, during which a colony of nearly 500 people dwindled down, due to hunger and disease, to 60 stalwart survivors.

The Building Them Up, Knocking Them Down project has students assemble arguments from suggested argumentative claims and selected passages on the question over whether Elizabeth loses her essential humanity due to the brutally extreme conditions of that winter. Then it has students participate in Refutation Two-Chance, so that they can respond to counter-arguments from against the arguments they have built on the issue. The project ends with an optional argument writing assessment.

Shaping Arguments: Feedback to Particular Patterns of Student Practice

We have been working with partner middle schools on the argument-based science/social studies project, called Shaping Arguments on Natural Resources. The Debatifier posted on this project recently. We have observed certain patterns of student practice in the implementation of this project, patterns that have elicited some of our feedback “analytics,” which we think may be of interest to the broader educator community using argumentation in the classroom.

The patterns of student practice itemized really do transcend the science/social studies content in this project (on whether the world faces a severe shortage of specific natural resources), and they also transcend the grade levels in which our partner schools have so far implemented it — both because Shaping Arguments on Natural Resources can be readily adjusted for implementation in high school, and because the patterned strengths and weaknesses that students have revealed are common to students across grade levels.

Logical Fallacies: Teaching Reasoning Skills by Examining Their Absence

Many, perhaps most, critical thinking and argumentation textbooks discourage teaching logical fallacies as a stand-alone unit. John Bean, for example, in his Engaging Ideas: A Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom (John Wiley & Sons, 2011), cautions that students will readily forget the names and definitions of logical fallacies when learned in the abstract, and that they are best learned when blended instruction focused on argumentation about specific content.

I’ve always been persuaded by this position and we recommend it in our work with middle and high school teachers. Acquire a facility with the various types of logical fallacy, and invoke them when most applicable in your regular argument-based instruction. Still, no pedagogical guideline like this should be viewed as an absolute rule, and recently we’ve come across a website that might help teachers elevate the place of logical fallacies in their effort to improve their students’ reasoning skills.