Two New Argument-Based Assessment Samples

Many schools have recently completed their semester-ending final exams. Teachers I was working with yesterday, for instance, told me that they were done with 85% of their essay grading from finals. They reported feeling both a kind of relief that they could see the light at the end of the tunnel, and a surge of motivation to finish, get their grades in, and feel that sense of accomplishment at having fully completed the semester.

This focus on the end of the semester got us thinking about posting on a couple of recent examples of argument-based assessments that we at Argument-Centered Education have developed with our school partners this year. What follows are two samples of assessment tools that have been used recently in our partners’ argument-centered classrooms. These tools can be used or adapted as is – they have been implemented successfully and are ready for wider use – but they can also be taken as models of the ways that argument-based instruction can connect to, generate, and be back-designed from argument-based assessments.

What Our Students Can Teach Us About Argument

By Dr. Jocelyn Chadwick

All is argument. Everything. Most individuals don’t even think of language and communication from this perspective, but most assuredly, Aristotle did. Often, we educators have made micro-delineations that are, frankly, too isolated and insular: expository writing is not similar to descriptive writing, is not similar to persuasive writing, is not similar to argumentative writing, is not similar to verbal expressions, and is not similar or relevant to any environment other than education. And not any of the previous delineations have any connections to literature or grammar and linguistics. However, argument undergirds and connects every verbal and written expression.

Dissolving the Obfuscation: How Acknowledging Our Argument-Focus Can Help Bridge K-12 and College

By Gerald Graff

Our trouble with schools may start much higher up—in an ivory tower. According to a recent report by some researchers at Stanford University, high school students with college aspirations “often lack crucial information on applying to college and on succeeding academically once they get there.”

Well, duh.

That the intellectual world of colleges and universities is incomprehensible to those who are not already at home in it has long been a common joke. It shouldn’t take a Stanford research team to tell us that when it comes to “succeeding academically,” many students don’t have a clue.

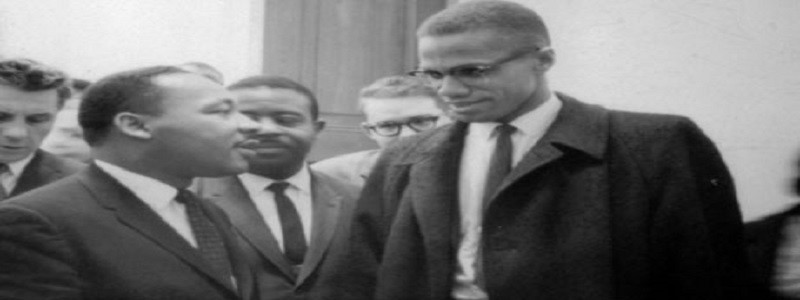

Civil Rights Strategy and Creating Argumentative Claims

It may seem like a settled question now, but in the early 1960s there was a fervent rhetorical struggle within the Civil Rights movement between advocates for non-violent strategy of civil disobedience (led of course by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.), and those for a black nationalist, radical militancy strategy of “any means necessary”(led until his shortly before his death in 1965 by Malcolm X). And of course the strategic directions of social movements and their progeny can change — there have been signs in the past few years (some in cultural expressions like hip-hop) that not all leading African-American voices are unquestioningly and immutably committed to non-violence. But even if there has emerged an unassailable consensus in favor of non-violent strategies to protest racial and social injustice, that doesn’t by itself mean that radical militancy would not have been more effective or productive in advancing the objectives of the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 60s (in argumentation theory, this idea is described by the fallacy argumentum ad populum).

Model Flowing on Google Sheets

In structured argumentation activities and classroom debating formats, tracking arguments on a graphic organizer — called a “flow sheet,” in competitive debate parlance — is essential. “Flowing” both enables and enforces refutation, and it makes the process of argumentation, and the unfolding of a debate, traceable and more objective. It may be the single most important way we have in argument-centered instructional work of de-mystifying — and therefore teaching — the process of academic argumentation.

But flowing is a complex and difficult activity — actually series of activities — involving critical listening, summary, and refutation itself. So it is important that the teacher model flowing; we are proponents of extensive modeling, and even when you’re requiring that students be flowing independently, you can be flowing for students as a model, and so that they can consult your flow when they (almost inevitably) lose track or get lost during the debate.