Responding to and Refuting Conflicting Interpretations — Junot Diaz’s ‘Drown’ (Part 2)

This post — which focuses on a method of teaching students to respond to and sometimes refute literary interpretations that conflict with their own — is the second part of a two-part look at an argumentalized unit on Junot Diaz’s first collection of stories. Part 1, on teaching students to analyze passages closely through argument, can be found here.

Analyzing Literature Closely through Argument — Junot Diaz’s ‘Drown’ (Part 1)

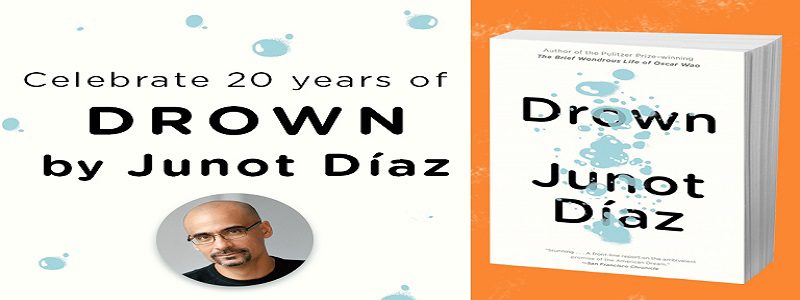

We have worked with partner schools on units teaching Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street, for many years probably the most frequently assigned works of Latinx fiction in high school. This year, though, we have been fortunate to work with a partner school with an especially robust Latino-American Literature course, and through that course we have collaborated on argumentalizing some very accomplished, very engaging literature written by Latinx writers. One such work is Pulitzer Prize and McArthur Fellowship winning author Junot Diaz’s first collection of stories, Drown (1996).

Collaboratively Created Response and Refutation Builder

A teacher at one of our partner high schools, Williams College Prep (Chicago), assimilated some of the resources that we’ve been sharing with and suggesting to him, and from them created an especially useful variation of his own. AP Language and Composition teacher Thom Connor has been focusing a lot of instructional attention on teaching students to think through, articulate, and incorporate into their essays careful consideration of the counter-arguments to their argumentative positions. He’s been teaching various ways of responding to or refuting these counter-arguments, as well. And he designed a builder that adapts Argument-Centered Education versions into something that he feels comfortable with and that works especially well with his students.

Argumentalizing ‘A Raisin in the Sun’

Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun is a sturdy classic of 20th century American literature and African-American literature and history, and it deserves to be as widely taught in high school English classes as it is. We have worked with multiple partner schools on the work, and our projects have been honed through iterative implementations to focus on several debatable issues, but one in particular.

Beyond Changing Opinions: The Enduring Impact of Debate

Even if you make no progress in changing anyone else’s mind, you may end up changing your own. Debate is like a stone that sharpens a blade. By forcing you to defend your arguments in a rigorous way, it compels you to think more deeply about them.

Are you among the millions of Americans who, in the year or so since the 2016 presidential election, have found themselves shaking with frustration at the refusal of a friend, family member, or colleague to accept a premise that seems beyond dispute? Have you argued, over Thanksgiving dinner or on social media, until one of you stormed away huffing and red in the face? Do you despair at the seemingly hopeless task of reconciling your own beliefs with those of the other half of the country? Well, I have bad news, good news, and a bit of advice for you.

The bad news is that a logical argumentation is not a particularly effective tool for changing the mind of a person you’re arguing with. I say this as a dedicated debater and teacher of debate. Unfortunately, what we know of human psychology suggests that directly challenging a person’s beliefs can even have the opposite effect, further entrenching those beliefs and making them more resistant to change. People circle the wagons, so to speak, when they feel attacked. They close their minds, and in the process of arguing they often come to hold their original beliefs even more strongly.