Civil Rights Strategy and Creating Argumentative Claims

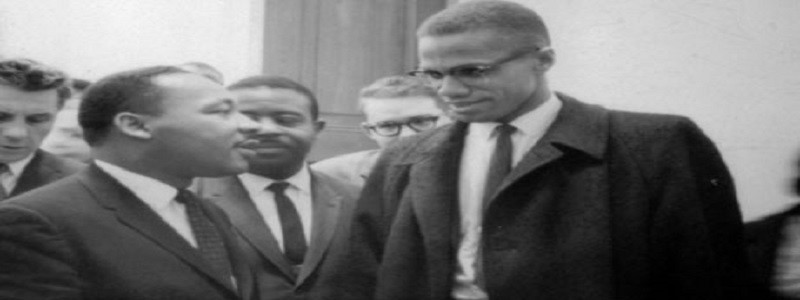

It may seem like a settled question now, but in the early 1960s there was a fervent rhetorical struggle within the Civil Rights movement between advocates for non-violent strategy of civil disobedience (led of course by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.), and those for a black nationalist, radical militancy strategy of “any means necessary”(led until his shortly before his death in 1965 by Malcolm X). And of course the strategic directions of social movements and their progeny can change — there have been signs in the past few years (some in cultural expressions like hip-hop) that not all leading African-American voices are unquestioningly and immutably committed to non-violence. But even if there has emerged an unassailable consensus in favor of non-violent strategies to protest racial and social injustice, that doesn’t by itself mean that radical militancy would not have been more effective or productive in advancing the objectives of the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 60s (in argumentation theory, this idea is described by the fallacy argumentum ad populum).

Argument-Centered Education has worked with teachers at multiple schools and across several departments (history, English, and humanities) to build resources around this issue. This instructional project on Civil Rights strategy starts with this debatable issue:

The Civil Rights movement ultimately proved that Martin Luther King’s strategy of non-violence was more effective than a radical ‘any means necessary’ strategy would have been.

Students have been viewing videos and reading secondary source material from a media list:

Teachers have been building argument-based content delivery strategies, including guided discussions, presentations, small group “with the grain” and “against the grain” reading activities, and evidence collection and itemization. One particularly powerful resource from the media list is the “debate” between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, created by video montage and juxtaposition.

Teachers have been building argument-based content delivery strategies, including guided discussions, presentations, small group “with the grain” and “against the grain” reading activities, and evidence collection and itemization. One particularly powerful resource from the media list is the “debate” between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, created by video montage and juxtaposition.

We do recommend that you use the downloaded and further edited version of this video, in the Partner Resources section of the Argument-Centered Education website; we removed a non-academic “joke” at the end of the video.

We do recommend that you use the downloaded and further edited version of this video, in the Partner Resources section of the Argument-Centered Education website; we removed a non-academic “joke” at the end of the video.

Students next have worked on a DBQ assembled for the project, one that has a set of argument-based questions that students have responded to in pairs. It is important that questions in a DBQ being used in the context of an argument-centered project also be argument-based. There are an almost limitless number of angles for study on writings and speeches from King and Malcolm X at the height of the Civil Rights movement; our argument-based questions maintain students’ focus on the evidence and reasoning that they will ultimately need to draw on in their arguments and counter-arguments on the debatable issue around the strategy options for the movement.

This argument-based content immersion led the students to the threshold of the argument building stage. But we wanted to focus on and exercise students’ capacity to infer argumentative claims from evidence, and to assimilate the structural concept that arguments (beginning with claims) are reasons to develop and defend an argumentative position on the debatable issue. So we adapted Argument-Centered Education’s Argumentative Claim Creator Activity for these purposes.

This argument-based content immersion led the students to the threshold of the argument building stage. But we wanted to focus on and exercise students’ capacity to infer argumentative claims from evidence, and to assimilate the structural concept that arguments (beginning with claims) are reasons to develop and defend an argumentative position on the debatable issue. So we adapted Argument-Centered Education’s Argumentative Claim Creator Activity for these purposes.

Students again work in pairs, but this time the pairs are formed by matching one pro-MLK student with one pro-Malcolm X student. Each of them reads through the seven pieces of evidence culled to support their position from the resources studied previously. Each piece of evidence theoretically can be used to support a different, distinct argumentative claim on their side of the debate. Students use the Argumentative Claim Creator Form —

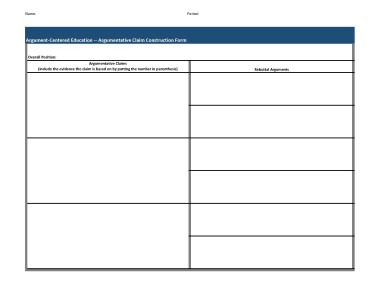

Students again work in pairs, but this time the pairs are formed by matching one pro-MLK student with one pro-Malcolm X student. Each of them reads through the seven pieces of evidence culled to support their position from the resources studied previously. Each piece of evidence theoretically can be used to support a different, distinct argumentative claim on their side of the debate. Students use the Argumentative Claim Creator Form — — to formulate and write out the three best argumentative claims they can generate, from three pieces of evidence, to support their position. Students put the evidence number in parenthesis after their claim, on the form.

— to formulate and write out the three best argumentative claims they can generate, from three pieces of evidence, to support their position. Students put the evidence number in parenthesis after their claim, on the form.

It might be helpful to consider the two model argumentative claims embedded in the activity. For the overall position in favor of the debatable issue (or proposition — Civil Disobedience Was a More Effective Strategy — the model evidence comes from Martin Luther King’s April 4, 1957 speech entitled “The Power of Non-Violence”:

Nonviolent resistance is not a method of cowardice. It does resist. It is not a method of stagnant passivity and deadening complacency. The nonviolent resister is just as opposed to the evil that he is standing against as the violent resister but he resists without violence. This method is nonaggressive physically but strongly aggressive spiritually.

Our model claim is:

Civil disobedience’s spiritual aggressiveness matches radical militancy’s physical aggressiveness.

For the opposite overall position, opposing the debatable issue — Radical Militancy Would Have Been a More Effective Strategy

— the evidence comes from Malcolm X’s April 3, 1964 speech entitled “The Ballot or the Bullet”:

Well, I am one who doesn’t believe in deluding myself. I’m not going to sit at your table and watch you eat, with nothing on my plate, and call myself a diner. Sitting at the table doesn’t make you a diner, unless you eat some of what’s on that plate. Being here in America doesn’t make you an American. Being born here in America doesn’t make you an American.

Our model claim is

Civil disobedience will always fail since blacks cannot work for change within an American system that has never accepted them.

These models demonstrate the intermediate location of the argumentative claim between the breadth of the overall position and the specific detail and local purposes of the evidence. This theoretical understanding of the structural condition of the claim is to be explored in a future Debatifier post.

After students in their pairs exchange their Argumentative Claim Creator Form with their partner. Partners evaluate their partners’ three argumentative claims based on ACE criteria for effective argumentative claims:

- Clarity

- Focus

- Separation

- Consistency

- Researchability

And finally partners formulate 1 – 2 counter-arguments to each argumentative claim. The counter-arguments will themselves be made up only of claims — evidence and reasoning the flesh out the counter-arguments will wait for the next and final stage of the project.

In that culminating stage, students will develop their arguments using ACE argument builders, and prepare refutation to the counter-arguments that their previous partners generated in response to their argumentative claims. Then students will conduct Showdown Debates, tracked and evaluated by their peers. Argument writing will be turned in and assessed in the form of argument builders and adjudicative debate evaluations performed by students when they are observing, not debating.

This project is one of the “full-service” projects that Argument-Centered Education has been working on lately with a few of its partner schools. It demonstrates that even when calling on the range of college-directed thinking and literacy skills implicated by rigorous academic argument activities, we can drill down with greater formative and developmental emphasis on a key building block — in this case, the creation of argumentative claims.