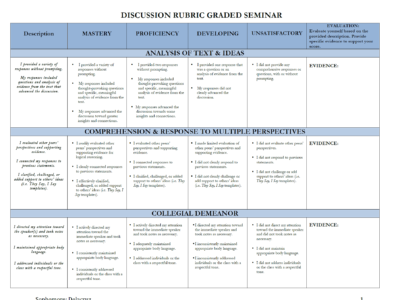

Joining the Conversation: Making a Space for Choices and Voices

By Patti Minegishi Delacruz

Those who have taught each grade level of high school will argue for a favorite – and perhaps least favorite – age group to teach. Five years ago, I would have claimed that sophomores are the most challenging group; this age group is arguably at one of the most difficult developmental junctures of their lives. However, this also makes them the most fearless and formative creators of arguments.

Over the years, I have observed how our “Joining the Conversation” unit is the most empowering unit of study for my sophomores in intermediate English, a course that serves a wide and unique range of skill-levels and social identities. This unit focuses on engaging students in argumentative thinking through accessing burgeoning opinions on timely issues, listening carefully to real voices speak on real problems, and developing own argumentative voices through verbal discussions and written products for an audience.

They Say, I Say, and More Stakeholders

At the start of the unit, I invite my students to explore real-life issues by brainstorming binaries that immediately interest them. This first step is a scaffold into thinking about arguments as conversations that can start with two sides but usually involve several perspectives. Based our introductory study of Dr. Gerald Graff’s and Dr. Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say, I Say (2006), students begin considering real conversations based on what they initially identify as “They Say” versus what “I say.”

First, every student creates an individual list of binaries. The following are examples of ideas that students brainstormed this year:

| They | I |

| College | No College |

| Abortion | Pro-Choice |

| Democrats | Republicans |

| Cubs | White Sox |

| Testing on Animals | Animal Rights |

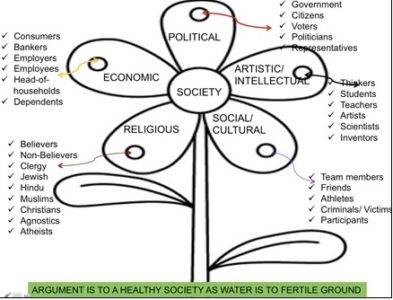

Once they take some time to independently think about multiple binaries, they engage in conversation with their assigned thinking triads (assigned small groups), recording one another’s binaries. As a group, students then try to organize their list across different realms of society that are presented to them through the following visual metaphor that I conceptualized to help recognize the range of issues that shape our society.

My students typically refer to this as the “Mutant Flower of Society” because of its bizarre aesthetics, especially once we start to identify the “stakeholders” in each of these realms:

Identifying the possible “stakeholders” also helps us reevaluate our list of binaries to recognize the plurality of voices that might exist for different issues. For example, the student who originally wrote college versus no college eventually discussed with her thinking triad the idea of college in the U.S. versus college abroad and then the greater problem of paying for college today and possible solutions to this problem.

As a class, we are also able to brainstorm a greater list of questions that inform multiple perspectives on an issue. For their first writing experience on an argumentative issue, students are required to formulate a debatable question on one controversial issue based on conferences with their thinking triads. Their question must allow for at least two perspectives on the question (i.e. they say versus I say) and must be supported by credible and relevant sources to back up not only the “I say” but the “they say.”

Modeling the Process of Reading for Arguments

I model this process of developing a debatable question and creating a claim in response to this question through our whole-class exploration of two high-stakes concepts: education and animal captivity. The first macro-question we consider is “What is the biggest problem in our education system?”. We study the following readings and multimedia to understand the different voices already in the conversation:

- David Guggenheim’s Waiting for Superman (documentary)

- “What Superman Got Wrong” (article)

- Ken Robinson’s “Schools Kill Creativity” (TED Talk)

- The New York Times’ Room for Debate on “Is Testing Students the Answer to America’s Education Woes?” (articles)

- The New York Times’ Room for Debate on “Should the School Day be Longer?” (articles)

We then explore the question of “should animals be kept in captivity?” and study the following sources:

- Gabriela Cowperthwaite’s Blackfish (documentary)

- Seaworld Cares’s “Why Blackfish is Propaganda, Not a Documentary” (article)

- The New York Times’ Room for Debate on “Does Captive Breeding Distract from Conservation?” (articles)

- The Washington Post’s “Endangered baby dolphin dies after swimmers pass it around for selfies” (article forwarded to me by a student)

- The Daily News’ “Two peacocks die in Chinese zoo after visitors plucked out their feathers while taking selfies” (article forwarded to me by a student)

Listen and Respond

For each of these debatable questions, students not only practice their reading skills for informational texts, but they practice their speaking and listening skills through both shorter, small group conversations and sustained seminars with the whole class. Small group conversations occur within thinking triads; these small group discussions are a necessary step for students to practice listening and verbalizing their thinking around issues of their choice, the education debate, and the question on animal captivity practices. Students record notes from their triad conversations, a consistent practice throughout the year. As a whole class, we engage in a seminar on both the education debate and animal captivity practices given our exploration of the different voices around these issues. The seminar is scaffolded into the following steps that privilege the comprehension of voices around the speaker as well as the development of one’s voice entering the conversation:

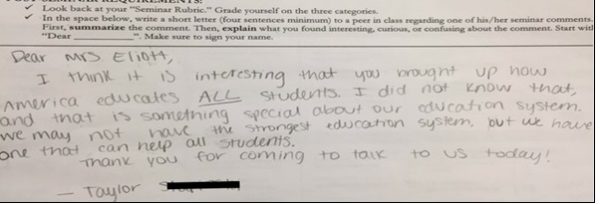

What is particularly enlightening about our seminar on the conversation about problems in our education system is an opportunity to hear from voices even outside of our own classroom. My third period this year was able to pose questions to our principal on his thoughts about education. In my first period class, our Assistant Principal of Curriculum and Instruction actually participated in our seminar, raising her hand along with the students and offering her own evidence to support her claims. The following is the post-seminar response one of my students wrote to her assistant principal right after the seminar:

The Reading, Speaking/Listening, and Writing Connection

By the end of this unit, students write extended paragraphs supported with researched evidence on a debatable question of their choice, the question of “what is wrong with our education system,” and the query “should animals be kept in captivity.” In total, they research and support a claim on these three controversial issues across 1-2 paragraphs that they submit for both peer and teacher feedback. As a summative assessment, they choose to take one of the three argumentative questions and develop it into a full researched argument, developed across multiple paragraphs.

I am transparent with my students about the importance of choice when deciding on the argumentative question to pursue for their culminating writing product. I find that about 60% of my students pursue either the education or animal captivity controversies to further investigate because they become more invested in these questions as our class explores these issues or because they need the additional scaffolds as readers and writers. This is especially true with most of my students requiring accommodations through their 504, IEPs, or EL transition needs. Other students pursue their own questions on controversies such as whether or not college athletes should be paid, or whether video game restrictions are necessary. These students are particularly motivated to investigate these questions because they already see themselves as knowledgeable about college sports and video games.

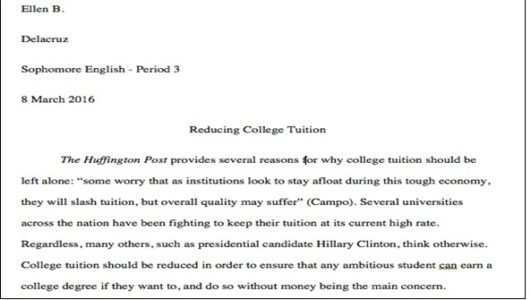

What we emphasize most in the argument, regardless of their choice of question, is the conversation; therefore, my students are challenged to start their arguments not with the typical attention-getter, but with a delineation of a counterargument. The following is an introduction from one student’s self-selected argument on “what should America do about the high cost of college?”:

Here is another student’s introduction that enters a conversation on the ethics of animal captivity, again calling attention to the naysayer – Seaworld – before she advances her own position:

What I also encourage my students to consider is the audience for which they are writing: their own classmates who will peer review their arguments, teachers like myself, future educators, and even admissions officers to colleges. Given this varied audience, some of the students will integrate reflections on the voices from the class seminar. Here is an example from one student’s formative argument on problems of the education system in which she refers to her peer Arash’s comment during the seminar to develop her own thinking around this question:

While this unit takes approximately six weeks for sophomore students, I have adapted facets of this unit at different rates and depths for upperclassmen in AP Language and Composition and my journalism students in their own journey of argumentative thinking.

This unit can be distilled down to three key tenets: the value of voices, the need for choices, and the necessity of spaces to engage in real conversations with real people. I have found that my sophomore students are especially passionate about these conversations because they are eager to be heard, out loud and on paper. But first we must listen.

Patti Minegishi Delacruz is an English teacher at Wheaton North High School (Wheaton, IL). She teaches AP Language & Composition, journalism, and sophomore English. She has a M.Ed. in Language, Literacy, and Culture from the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is a 2015 Fellow of the Chicago Area Writing Project.