Arguing about Ancient Chinese Philosophy — the Confucianism vs. Daoism Project

We worked recently with a partner school’s Global Studies course and their Ancient China unit. The outcome: an argument-based small group discussion project on Confucianism and Daoism.

The post below includes resources which focus on the way that arguments can be made about the desirability of certain systems of thought and the values they inscript. The project also uses a format of discussion that is looser and less rules-based than a debate (though, of course, rules have their utility and place, when striving to reach certain levels of rigor in a scaffolded academic setting). Finally, this project is an example of the way that an argument-centered approach has the agility to incorporate varied curricular resources — in this instance, some SHEG (Stanford History Education Group) document excerpts and background information.

Overview

When studying the ancient China in a world studies curriculum, one of the cultural touchstones are the vastly influential and lasting philosophies of Confucianism and Daoism. Chinese philosopher Confucius (551 – 479 BCE), as part of the larger Hundred Schools of Thought, laid down the tenets of his worldview in the Analects. Confucianism is a humanistic philosophy, which places great weight on filial piety and respect for elders; a commitment to hard work as essential; and the universal values of compassion, justice, and courage. Confucianism would wax and wane in influence through subsequent Chinese dynasties, though its presence is quite clearly felt throughout Asian societies till this day.

Daoism is generally attributed to the thinking of Lao Tzu, a Chinese philosopher of the late fifth century BCE. The masterwork here is the Tao Te Ching, generally translated as The Classic of the Way and Virtue. The Dao is “the Way.” It has a mystical essence, but is a flow or feeling of oneness with nature; acceptance of things and renunciation of desire and resistance; modesty and selflessness; and a recognition that all things are inter-connected. Daoism holds that there is a Yin and a Yang – opposites always attached to and interpenetrating each other – that is a universal structure and composition of things. There is no evil without some good, no beauty without some ugliness, no life without death. Daoism has also exerted great influence over Asian and world cultures and worldviews through the centuries.

Debatable Issue

The debatable issue for this project is:

By which ancient Chinese philosophy should people today be more influenced, Confucianism or Daoism?

It is important for students to understand that in arguing for one or the other philosophy they are not necessarily taking the position that people should become Confucianist or Daoist. Rather, they are arguing that their philosophy should influence the way people today live, and it should so do because of the values that it espouses and beliefs that it teaches.

Method and Procedure

This project incorporates material from the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) project on this topic.

(1)

Students should be paired with a partner. Generally, we would recommend that these pairings be heterogeneous, serving differentiation goals, though the best pairing strategy is usually made based on a closer, more specific understanding of students and their propensity to work productively with certain classmates more than with others.

(2)

Introduce Confucianism and Daoism – their historical contexts, their main tenets, and their influence. Have students define key terms. Present the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG) slides. Assign students reading on these ancient Chinese philosophies from the textbook, if one is being used.

(3)

Establish the debatable issue, explaining that student pairs will take one position or the other – either that Confucianism or Daoism should more influence people today. Explain that students do not to take the position that people should convert to one of these philosophies or religions, but that one or the other should be more influential.

Pairs can be given a choice over which position to take, as long as there ends up with a balance between the two positions, or they can be assigned a position.

(4)

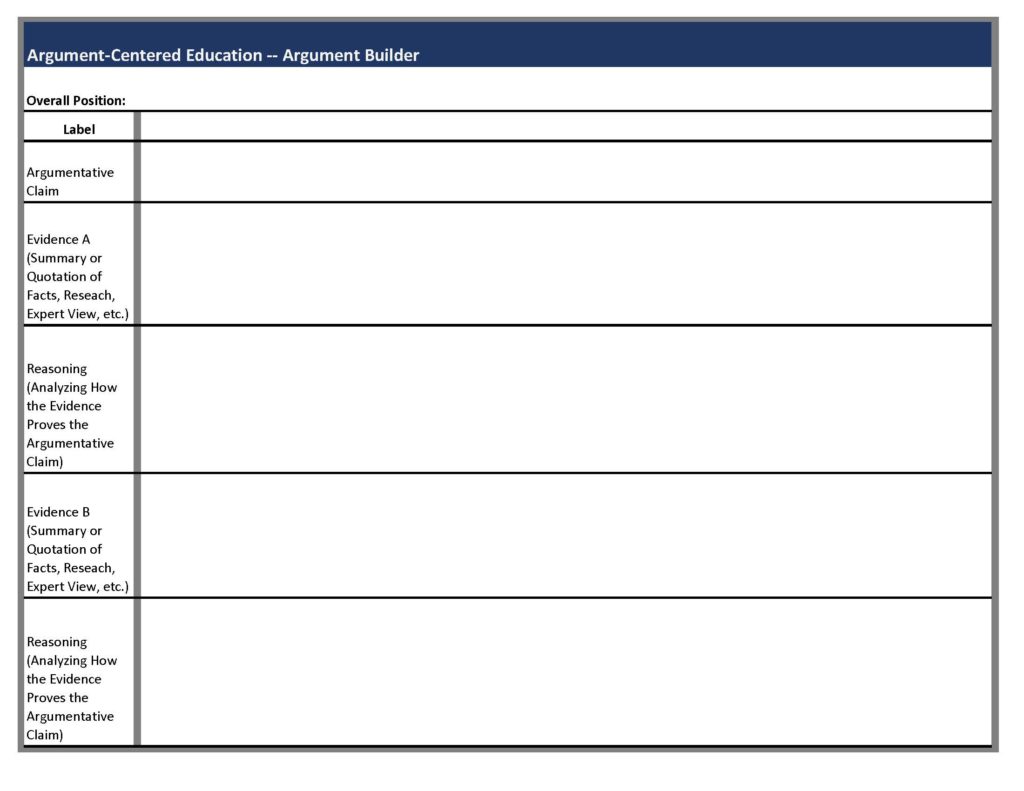

Students should be told that they will be building two (or three, for more advanced students) arguments in support of their position. The arguments that they build will consist of a claim that specifies a belief of the philosophy they are arguing for, evidence that quotes text (a quotation or a passage from a SHEG document) that demonstrates that philosophy includes the belief identified in the claim, and reasoning that both explains how the evidence evinces the belief and describes why it is that this belief should be embraced and adopted by people today.

Here is a model argument.

Claim

Daoism believes in non-violence and rejects the use of weapons against other human beings.

Evidence

“Weapons are ominous tools. They are abhorred by all creatures. Anyone who follows the Way shuns them” [Tao Te Ching chapter 31].

Reasoning

The “Way,” which is the sacred path for living to Daoism, has people fully committed to non-violence and even to “abhorring” and “shunning” all weapons. American society is far too violent today, and we would be much better off if weapons were shunned instead of purchased (legally or not) and used to commit violent acts. The mass killings in Las Vegas is only the most recent example of this country’s love of guns and tolerance of violence.

The claims can use this standard template: [Confucianism or Daoism] believes that [fill in the belief that can be substantiated by the evidence]. This consistency will scaffold argument building on this issue for students who are not more advanced in their academic argumentation skills. The weight here is – as with many arguments – on the student’s reasoning, which has to both connect the evidence and the claim, and explain why the belief identified in the claim is one that everyone today should embrace.

Distribute argument builders, one per student.

(5)

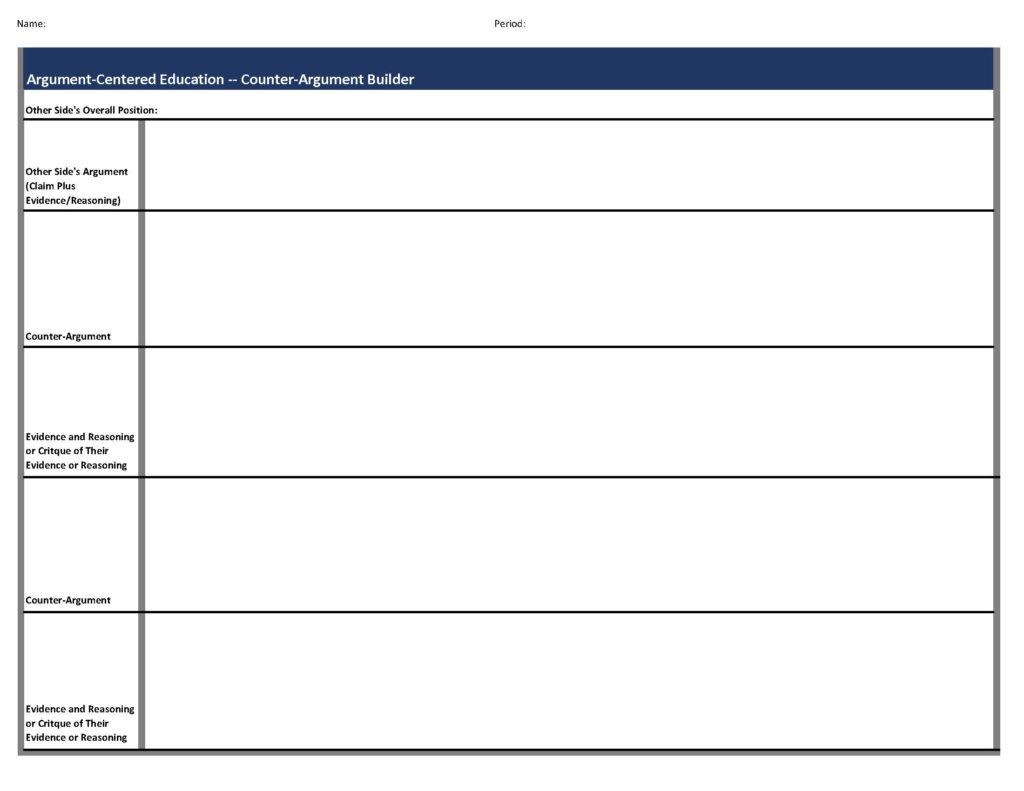

Students should also be told that they will be matched with another pair of students that are taking the position opposed to theirs for culminating small-group discussions. Pairs will exchange their argument builders so they can review the arguments that the other side will be making in their discussion. They will need to make counter-arguments (one or two) in response to each of the arguments being made by the other side.

Each counter-argument can be one of three types. (1) The counter-argument can say that its side’s philosophy also has and shares the same belief in the claim. (2) The counter-argument can say that the evidence included in the argument doesn’t substantiate the claim that the other side’s philosophy has this particular belief. (3) The counter-argument can say that this belief shouldn’t be embraced by everyone today, or that it isn’t as important as beliefs held by its side’s philosophy.

Distribute counter-argument builders, one per student.

(6)

Distribute the SHEG document excerpts and the Confucianism and Daoism quotations. Students should be told that the SHEG close reading questions are to be adjusted from “the three features of an ideal government” to “the three features of the proper way to live with others.” Students should discuss the responses to these questions and complete one set of questions, submitting them for formative assessment.

(7)

With the quotations, the following activity should be used. Students’ desks can be arranged in a circle, and they should sit next to their partner. Beginning with the Confucianism quotations, going around the circle, each student should stand and read a quotation, slowly and loudly. Another student should be chosen at random to paraphrase the quotation. When all the Confucianism quotations have been read, students should identify their most favorite and least favorite in a quick-write, a few of which can be shared out. Do the same for the Daoism quotations. The purpose of this activity is to bring students in closer to these highlights from each philosophy.

(8)

A classroom-wide discussion should be done around possible argumentative claims – which in this context is another way to say, a discussion around the tenets and beliefs of each philosophy. Consider whether to distribute the Possible Claims document, or whether to have access to it for teaching purposes as needed to help guide the discussion and keep it moving down the rails, so to speak.

(9)

Pairs should build their arguments. They should get guidance and support as they need. Pairs should submit their work for formative assessment. They should get feedback, and their argument builders returned for revision.

(10)

Pairs should be grouped with pairs taking the other position. Pairs should exchange their finished argument builders, so that they can read them before building their counter-arguments. Students should be reminded of the three types of counter-arguments possible here. If possible, collect the counter-argument builders and offer feedback on these, for revision.

(11)

Students (in fours, two pairs of two) are ready now for an argument-based small group discussion. The discussion can begin with each side offering up its two arguments, then it can proceed without formal speech sequence. Students can use their counter-argument builders for notes. Students should be encouraged to respond to each other’s points, though they can also concede points where they feel inclined to. These discussions – taking place simultaneously – should last about 25 minutes. They can conclude with a teacher-led sharing-out.

(12)

Students should write a detailed summary of their discussion, which includes an evaluation of who made the strongest arguments and why, as a summative assessment.