Annotation Strategies in Use in Argument-Centered Classrooms

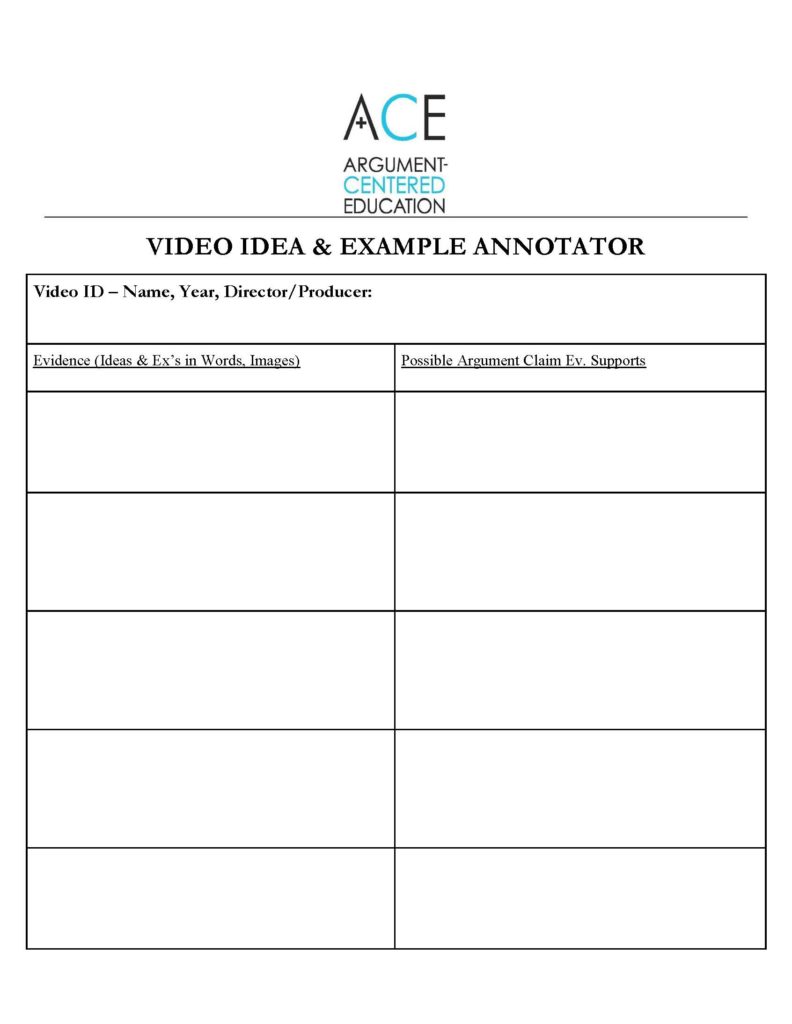

Video Idea and Example Annotator

This annotator is for use when you are using a video or visual representation in your instruction. It is explicitly argument-based, so it works with projects in which students are viewing “text” so that they can become informed about, and have ideas, about an issue, so that ultimately they can produce arguments on the issue This annotator can be used prior to students knowing what their position will be on an issue, because students should use it to capture ideas that they have about the issue, generated by something they see or hear in the video. These ideas are raw resources and materials for formulating and building arguments later.

There is also a sample of a completed page of the Video Idea and Example Annotator, using a short video on the issue on social media — i.e., Does social media make teens (or kids) less social? Two notes on this example. (1) On the ideas/examples side (which is labeled “evidence,” but should be thought of broadly, since it isn’t yet clear to students what evidence they will use or need), you’ll notice that there is mostly paraphrase, but an occasional quote appears, too. It is only feasible for students to capture quotations if you either flag them for students by pausing the video, or if you play certain sections of the video more than once. (2) The argumentative claims column is only completed after the ideas and examples are captured. Students should not try to complete the argumentative claims column while the video is still running, since it isn’t feasible to both collect evidence and formulate possible claims at the same time.

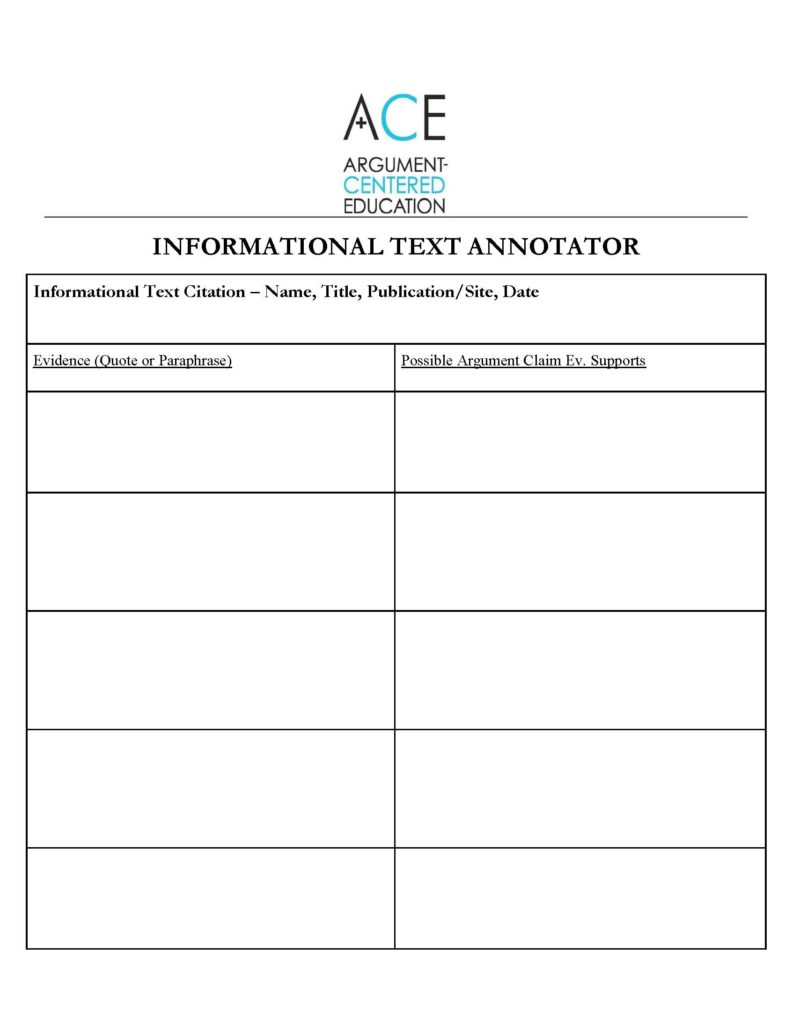

Text Annotator

The structure of this organizer is the same as the Video Idea and Example Annotator. It is to be used along side of the reading of a written text. This annotator is generic and universal enough to be used in any subject area and almost any written text. It is also argument-centered and useful in the process of gathering evidence and formulating ideas on a debatable question.

To be used effectively, however, it requires that teachers give content-specific and project-specific guidance to students on what kind of text might be useful — i.e., what students should be looking for, at least in a broad sense. If you want to use this instrument in a more scaffolded context, you should consider providing students with a set of possible claims and even a set of possible counter-claims.

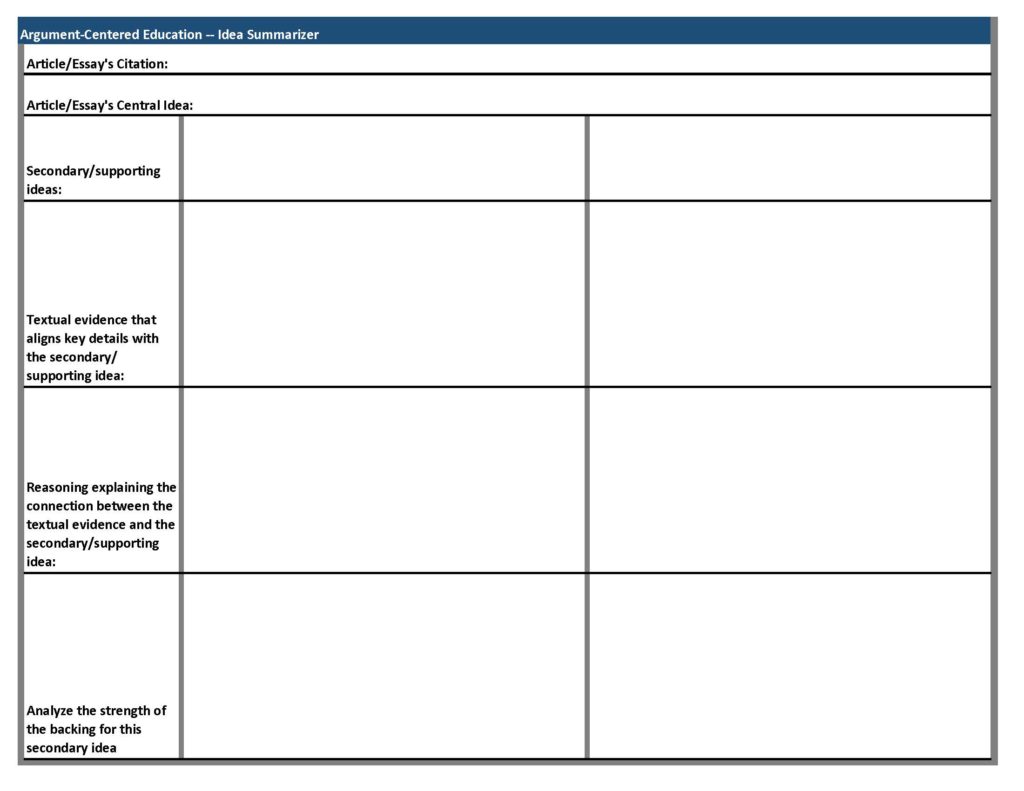

Idea Summarizer

This annotator is for use on the other end of the argument-centered spectrum: namely, reading and listening for argument, rather than preparing to write or speak argument. Students should be coming out of high school highly capable to do both ends of this spectrum very well, having had lots of practice, and having been immersed in a culture that not only does both routinely, and in every classroom, but also cultivates in students the ability to make distinctions in the quality of argumentation and teaches them to evaluate argumentation that they read, hear, or engage with in their own speaking and writing.

So, this organizer is useful to help students read and listen for argument. It uses the language “central and secondary ideas,” which is a little broader than “overall position and supporting arguments,” but obviously encompasses the latter. This annotator leans heavily in the direction of use with informational text.

Argument and Counter-Argument Building Annotation Method

I’ve attached two photos of examples of an annotation method that we have worked with teachers on, as students are reading and researching through a Media List. The examples here come from an argument-centered project on cosmetics and plastic surgery, with the debatable issue, Can cosmetics and plastic surgery make someone more authentically beautiful? The premise is that both examples come from a student who is arguing that they can indeed make someone more authentically beautiful.

If the article is supporting their position, as in Example A, the student should underline passages that could possibly be used as evidence to support one of their arguments (whether the passage ultimately is quoted or paraphrased), writing the possible argumentative claim the passage would support in the margins.

If the article is opposing their position, as in Example B, the student should write their skeptical questions or critiques of the article in the margin, and underline any of the text that makes important concessions, acknowledges contradictory evidence, or reveals important and possibly invalid assumptions.

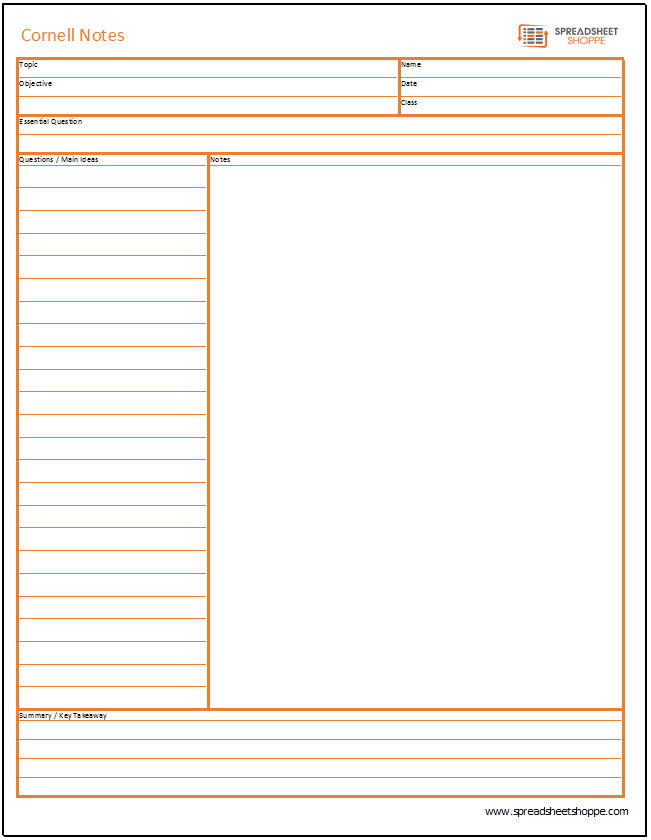

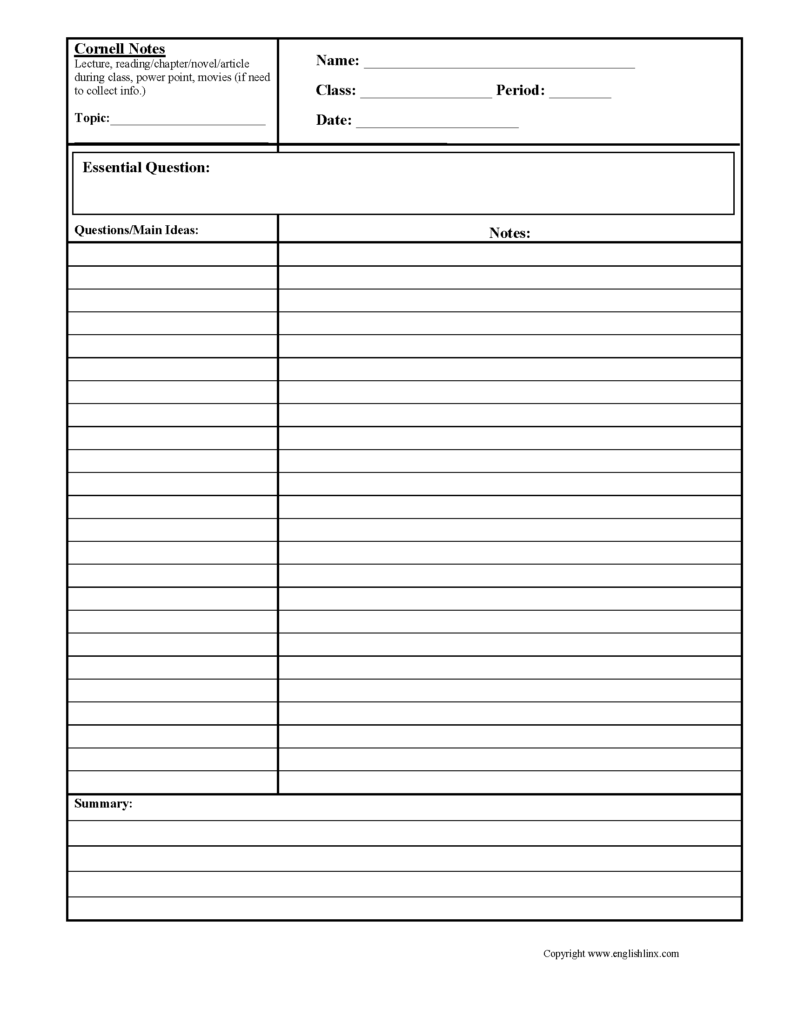

Cornell Notes

Cornell Notes — an annotation system developed in the 1950s College of Education at . . . wait for it . . . Cornell University — use an organizer that divides a sheet of paper into two sections with a vertical line, where the right column is twice the size of the column on the left. There is a band across the top to identify the student and course, and a horizontal line about a quarter of the page from the bottom, where the vertical line comes to an end. The bottom of the page summarizes the notes above it. The notes above: on the right, larger column, the student copies down important points, data, information, and on the left either (a) labels that make sense of that information or categorize it in some way, or (b) questions that that information elicits.

I’ve attached three similar examples of a Cornell Notes organizer. As the also attached model suggests, Cornell Notes are often used by students listening to a speaker or lecturer (that was their original intended purpose), and are more often used in science (in my experience, anyway) than the other subject areas. Nevertheless, I can conceive a way to adapt the traditional Cornell Notes design to something that suited needs across disciplines, especially annotation needs in argument-centered, critical thinking focused contexts.

This post is intended to provide Debatifier readers and Argument-Centered Education partners with annotation resources, and to foster and advance professional discussion over what annotation method(s) teachers want to use in their argument-centered classrooms.

This post is intended to provide Debatifier readers and Argument-Centered Education partners with annotation resources, and to foster and advance professional discussion over what annotation method(s) teachers want to use in their argument-centered classrooms.

Two additional thoughts.

First, I don’t think that it is necessary to adopt a single annotation strategy throughout the school. Making consistent our use of the language of argument prevents students from becoming confused about or misunderstanding argumentation concepts because different teachers are calling the same things different names. That’s a good kind of standardization. But we wouldn’t want to entirely standardize teaching styles and methods across classrooms, would we? Different annotation methods, built around consistent language and concepts, seem to me to fall closer to this latter category than the former. What’s more, different disciplines have different applications of the annotation process and — perhaps most importantly —

annotating to build interpretations, conclusions, solutions, answers, evidence-based ideas — arguments — is a categorically different cognitive process than reading or listening for ideas, views, conclusions, suggestions, positions — arguments.

Second, here, as in certain other contexts, I think there is utility, if not beauty, in simplicity. I have seen elaborated coding systems, where students’ reactions to a text can be expressed in a dozen or more separate symbols that they apply to the text — heart shape for a line they love, exclamation point for something really important, equal sign when something they read reminds them of something they already know, etc., etc. — but I have not myself seen these systems work well in practice. A simple system — embedded within an academically purposeful project (what am I reading this text for? what will be I asked to produce or demonstrate?) has seemed in my experience to work far better.

If you use any of these annotation strategies to advance the effectiveness and your instruction, helping make it more college-directed and academically riveting to students, let us know how it goes. This kind of feedback is an important part of how we improve our support for partners and advance in production of resources that best serve middle and secondary school teachers.