Identifying Core Binaries to Conquer Free Response in AP Comp

Brady Gunnink, who teaches AP Language and Composition at ACE partner school Jones College Prep in Chicago, came to me earlier this semester with a challenge: can we work together to build a strategy with supporting resources that can help his AP Comp students improve their writing on the Free Response essay questions on the AP exam? Students, he said, often find the third question of the three FR questions the most difficult; it is the one for which there are no sources or texts and students are asked to write an argument in response to an abstract or philosophical proposition (e.g., philosopher Alain de Botton has said that humorists play a vital role in society in that they are able “to convey with impunity messages which might be dangerous or impossible to state directly’ — write an essay taking a position on this viewpoint). The outcome of this collaboration at Jones and my work to create a writing strategy is the topic of this post.

Overview

The third free-response question on the AP English Language and Composition exam is one in which students are asked to take a position on an open, contestable proposition, and to support that position with arguments whose evidence is to come from “your readings, experience, or observation” (in the words of the 2016 AP exam), rather than from sources provided in the exam. For a lot of students, the task of both organizing and coming up with evidence-based arguments on an issue for which they do not have textual sources is uniquely challenging.

But there are ways to approach this situation to produce a well-evaluated essay, despite its inherent difficulty. There are elements of academic argumentation that apply to the rhetorical situation that students are in when responding to this question that are, you might say, universal, and that can position students to succeed with their essay, despite being on unfamiliar content-ground. There are structures of argument, and argumentative moves, that can be deployed to help you achieve an “effective” score (7 or 8), and possibly even the highest score (9).

The Core Binaries Strategy

here is a three-step pre-writing strategy that we recommend you conduct in response to Question 3 in the free-response section of the AP Language and Composition exam. You should execute this strategy flexibly; with questions that you have quick and substantial ideas on how you will respond, it would make sense to apply this strategy more loosely, using it to help structure your argument, for instance, more than identifying oppositions. That said,

this is a sturdy, reliable strategy, which can serve to organize their thinking and help writers produce an AP-approved argument essay in a very short time on a topic in which they are not well versed, knowledgeable, or prepared.

Step One: Identify Oppositions

Rooted in every prompt or question or controversial issue to which you are expected to make arguments are oppositions, opposing terms, conflicting ideas. Sometimes these are multi-faceted, but often they can be expressed as a set of binaries. From these binaries, a straightforward or more nuanced position can be constructed. So, to get a handle on the question, to begin to think about how you can take a position supported by arguments, and to itemize evidence, the student should first identify the core oppositions embedded in the prompt.

Identifying several core binaries explicitly or implicitly embedded in the prompt will enable you see what your argumentative options are and to efficiently and even spontaneously generate ideas for evidence that will support certain options more than others.

Step Two: Manufacture Examples

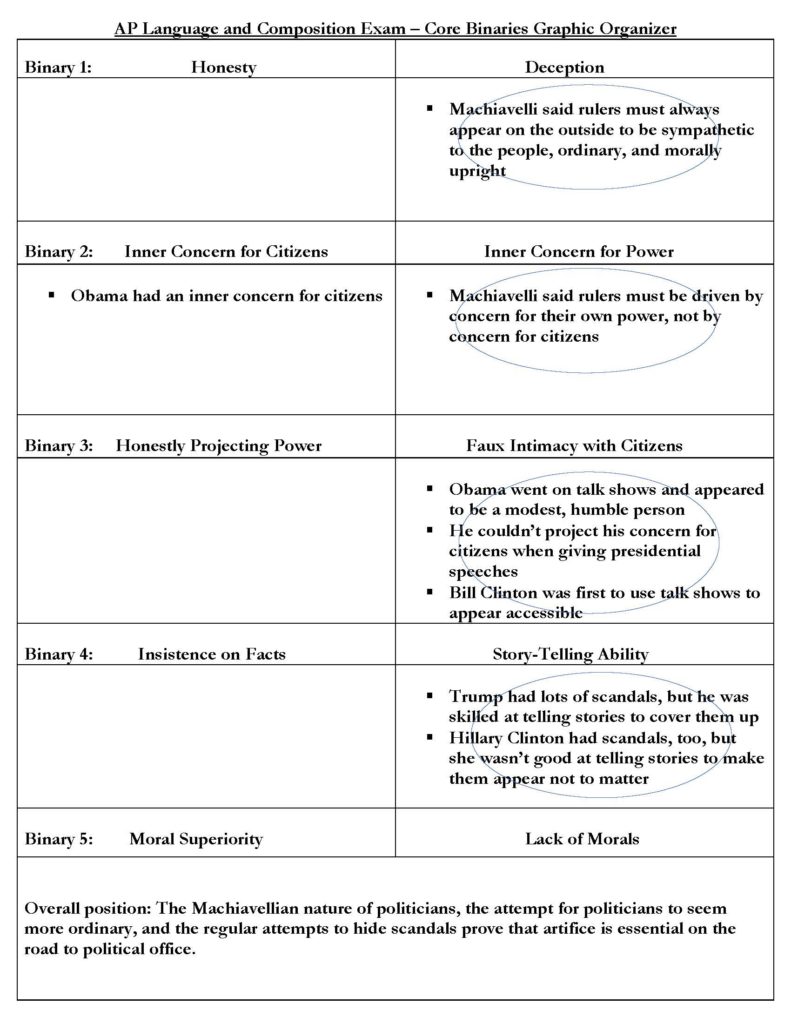

This Core Binaries Strategy includes a simple graphic organizer in which a student can identify three to five core binaries in the question From there, students should list under binaries heading the examples they can manufacture. Students are not able to bring this graphic organizer into the actual AP exam, but it is a simple T-chart in design, and practicing it a few times will enable them to set up the graphic organizer very quickly on a single sheet of paper in their answer booklet.

A key challenge in this question type is that the students is not given sources from which to derive evidence to support their arguments. The implication of setting up the core binaries is that they will supply the ideas that students can formulate into claims (i.e., arguments that will get fleshed out and evidenced in body paragraphs). But the evidence itself the student will need to manufacture. This means that they will need to quickly list out one or two examples from their prior or personal knowledge that support at least one side of the binary, for three to five binaries.

Step Three: Structure Arguments

Now the graphic organizer students are using (or that they very quickly created on a sheet of paper) should have three to five core binaries on it, and manufactured examples in as few as three, and as many as six, fields under each half of the core binaries. If a student has five core binaries identified, it is possible to have manufactured examples in as many as ten fields, but it would most likely consume too much of their allotted 40 minutes to prep this thoroughly. Once a student has several solid manufactured examples, in light of the above criteria, they should move on to structuring their arguments.

In structuring arguments, they want to look for a pattern or connection between their strongest examples, those that they will be able to write about most fluently, with as much authority as they can, given very limited time. Students should circle these preferred and patterned examples and the half-binaries that they support. The writer needs to be able to find a through-line, pattern, or common connection between the fields they have circled. If an additional half-binary (or two) is what is preventing them from doing so, they should eliminate the impeding field and example, as long as they are still left with at least two, but preferably three to four. The way they make the half-binaries with examples fit together is, of course, their overall argument (what Argument-Centered Education and the College Board call their position or thesis). The writer should be able to say – mentally or in a whisper, they probably won’t have time to write it out separately – the formulation of your overall position. The half-binaries with examples themselves become their argument (body) paragraphs.

Resources

The most fundamental resource for the Core Binaries Strategy is the Core Binaries Organizer.

A model based on the higher-scoring student writing sample from the 2017 AP Language and Composition exam is below.

Argument-Centered Education has additional models which we have been using with partner schools. They lay out in further, scaffolded detail the way that the Core Binaries Strategy can be used by students in response to prior years’ AP Lang and Comp exams, which are available here on the College Board website, along with actual student essay samples.