Argument and Reasoning in Algebra: The Use of SAN Questions

By Conor Cameron

The Common Core State Standards demand that students of mathematics, “Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.” In a vacuum, that requirement probably seems more descriptive of what might occur in an English or social studies classroom. Many math teachers probably think to themselves, “Students may do that sort of work in their Geometry classes, not so much in mine.”

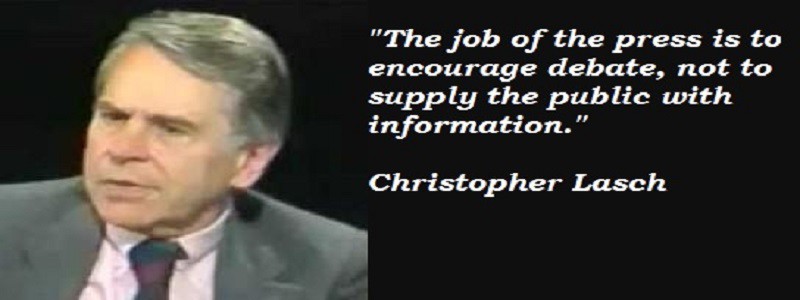

“But My Students Don’t Know Enough Yet to Engage in Debates!” Christopher Lasch on the Argument vs. Information Confusion

By Gerald Graff

“Hey, I’m all for teaching argument and debate,” my colleague assured me after viewing the ACE website. “But students have to know something about a topic before they can usefully debate it, and students these days just don’t.”

It’s one of the most familiar objections to organizing school and college curricula around debatable issues: until students know enough of the relevant information—as today’s students rarely do—they aren’t ready to debate such issues. And it’s certainly true up to a point: it’s hard to enter a debate about whether income inequality is a problem or not if you lack information about what’s been happening to income distribution over the last generation.

What this way of thinking ignores, however, is its circularity: yes, students need some economic knowledge to intelligibly debate the pros and cons of income inequality, but unless they are exposed to the debate they may not see the point of acquiring that data in the first place.

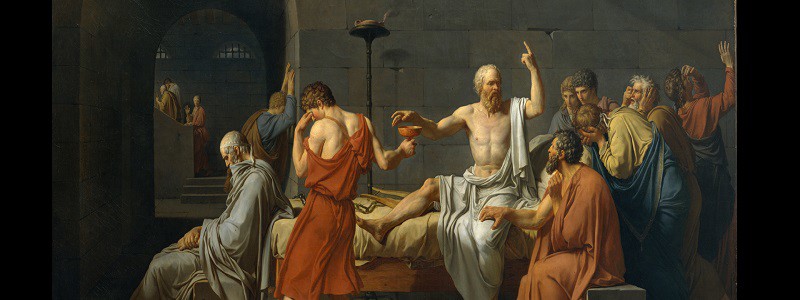

The Argument-Based Socratic Seminar

Named for Socrates (469 – 399 B.C.E.), one of the founders of Western philosophy, the Socratic Seminar is a formalized classroom discussion activity that emphasizes reflective thinking about big questions and the use of evidence to support responses. According to Elfie Israel, in Inquiry and the Literary Text (NCTE, 2002):

The Socratic seminar is a formal discussion, based on a text, in which the leader asks open-ended questions. Within the context of the discussion, students listen closely to the comments of others, thinking critically for themselves, and articulate their own thoughts and their responses to the thoughts of others. They learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and civilly.

An Unlikely Collaboration: College Forensics and Classroom Accounting

Northern Illinois University’s College of Business and Department of Communication were brought together several years ago over the common goal of developing student’s critical thinking skills. The connection nurtured a mutually beneficial relationship for both NIU departments, and all of the educators and students taking part. My involvement in the collaboration has grown throughout its development. It began with providing example debates as a senior undergraduate member of NIU’S debate team; then I provided more extensive support as a graduate intern; and now I am integrally involved with the project as its professional consultant.

The Five Steps to Argumentalizing Instruction

One of the signature features of the services model developed and employed by Argument-Centered Education is its embeddedness. Not only is its teacher coaching embedded within schools and active classrooms, so that teachers get observation-based feedback and targeted modeling support, but its curriculum design and adaptation works from curriculum that its partner schools and teachers are currently working with and to which they are committed. Instead of importing argument-based curriculum from outside, we work to build argumentation from the inside of an individual teacher’s, or department’s, or school’s, or district’s in-place instructional content and methodology.

External curricular components can often feel like diversions from the trajectory of a course. They can be and often are tried a couple times then quietly dropped. They can generate understandable even unspoken resistance from educators who entered the profession in part because they have an intellectual passion for certain fields of learning, things they know, and have dedicated their professional lives to sharing with the next generations. And they can impair the effectiveness of an on-going and embedded professional development strategy because they restrict demonstration of the use of argumentation to an external curriculum.