Controversy in the Classroom – A Compelling Introduction to a Pedagogy that Can Democratize 6th – 12th Grade Instruction

University of Wisconsin – Madison Dean of the School of Education Diana Hess is a national leader in argument pedagogy and civics education (and also an academic partner of Argument-Centered Education). Her first full-length publication, Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion (Routledge, 2009), helped make her reputation and forge her current trajectory of influence. In this review we’re going to investigate the close connections between the work’s pedagogical theories and 6th – 12th grade argument-centered instruction.

Professor Hess extols the civic and democratizing importance of structuring argument about controversial issues in middle school and high school. She presents a bevy of evidence for this conviction; one example is the 2003 report from the Carnegie Corporation titled “Civic Mission of the Schools,” which she quotes:

Studies that ask young people whether they had opportunities to discuss current issues in a classroom setting have consistently found that those who did participate in such discussions have a greater interest in politics, improved critical thinking and communication skills, more civic knowledge, and more interest in discussing public affairs out of school. Compared to other students, they also are more likely to say that they will vote and volunteer as adults (28).

Controversy in the Classroom provides an especially vivid quote from a teacher involved in one of the work’s referenced studies, developing the idea that arguing in discussion and taking part in classroom debate is essential for airing out differing ideas and views, and is in some ways a prerequisite for students coming to their own independent thinking on important issues that we teach in our classrooms.

Debate at the Poker Table

by Andrew Brokos

I was heavily involved in debate in high school and college, and as an adult I continue to volunteer with debate-related organizations. Professionally, though, I did not pursue a traditional “debater career” in a field such as law or politics. In fact, there’s nothing traditional at all about my career: I’m a professional poker player.

The connection between debating and playing poker is certainly less obvious than between debating and running for office, but the truth is that I credit a lot of my success in poker to the skills that I learned from debating, skills like critical thinking, considering all sides of an argument, and weighing advantages and disadvantages.

The Argument-Based Socratic Seminar

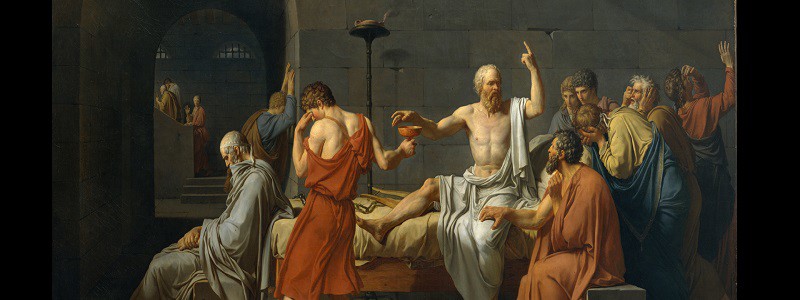

Named for Socrates (469 – 399 B.C.E.), one of the founders of Western philosophy, the Socratic Seminar is a formalized classroom discussion activity that emphasizes reflective thinking about big questions and the use of evidence to support responses. According to Elfie Israel, in Inquiry and the Literary Text (NCTE, 2002):

The Socratic seminar is a formal discussion, based on a text, in which the leader asks open-ended questions. Within the context of the discussion, students listen closely to the comments of others, thinking critically for themselves, and articulate their own thoughts and their responses to the thoughts of others. They learn to work cooperatively and to question intelligently and civilly.

The Five Steps to Argumentalizing Instruction

One of the signature features of the services model developed and employed by Argument-Centered Education is its embeddedness. Not only is its teacher coaching embedded within schools and active classrooms, so that teachers get observation-based feedback and targeted modeling support, but its curriculum design and adaptation works from curriculum that its partner schools and teachers are currently working with and to which they are committed. Instead of importing argument-based curriculum from outside, we work to build argumentation from the inside of an individual teacher’s, or department’s, or school’s, or district’s in-place instructional content and methodology.

External curricular components can often feel like diversions from the trajectory of a course. They can be and often are tried a couple times then quietly dropped. They can generate understandable even unspoken resistance from educators who entered the profession in part because they have an intellectual passion for certain fields of learning, things they know, and have dedicated their professional lives to sharing with the next generations. And they can impair the effectiveness of an on-going and embedded professional development strategy because they restrict demonstration of the use of argumentation to an external curriculum.

Why Argument Writing Is Important in Middle School

By Leslie Skantz-Hodgson and Jamilla Jones

Is argumentative writing important for today’s middle school students to master?

This past summer we were among six educators who thought diving into the argument aspect of teaching academic writing was important enough to gather during the break and share thoughts on a close reading of They Say/I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing (W.W. Norton, 3rd edition, 2014) by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein.

In addition to learning together, we also argued and debated together (a lot) about the strategies and beliefs reinforced in the text.

Looking inward and outward

We were a mixed group of teachers of disciplines — science, English language arts, humanities, special education — across the grade levels. Our inquiry work was supported by a grant from the National Writing Project.

Our common goal was to learn how to impress upon our students the value and importance of developing their arguments “not just by looking inward but…by listening carefully to what others are saying and engaging with other views.” (Birkenstein/Graff, p. xxvi)