Teens’ Social Media Use, the Argument Assembler, and Large Groups

Ninth grade social science classes at one of Argument-Centered Education’s partner high schools ended the school year conducting a rather fully developed argument-centered project on teens’ social media use. The debatable issue:

Teens social media use makes teens less social.

There was an interest in closing the year with a project that brought together strands of academic argument studied and practiced during the year with a topic that students would find appealing, perhaps a little entertaining, and with which they’d already be familiar. Since teens are purported to spend nearly nine hours a day on social media according to a 2015 study by the organization Common Sense Media (!), this debatable issue has the familiarity criterion covered.

Teaching the Content

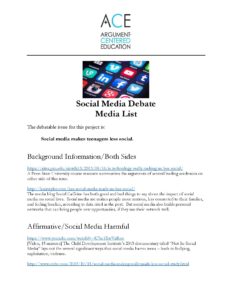

Content coverage begins with a media list, which the students researched for two days in the media center.

But before the article research, several of the videos on the media list were screened, including these two excellent short videos:

But before the article research, several of the videos on the media list were screened, including these two excellent short videos:

Preparing and Providing Claims and Evidence

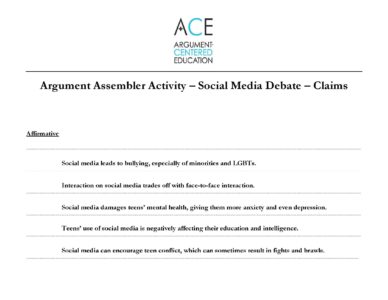

Many of the students in this particular cohort also needed a year-end project that was strongly scaffolded, according to the lead teacher. So we adapted the Argument Assembler Activity, with full supports in place. With the Argument Assembler, students work in pairs to assemble an argument on the issue, using an argument builder that they issued that has an argumentative claim already formulated on it. Here are the argumentative claims used in this Argument Assembler Activity.

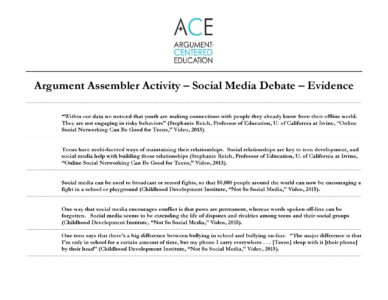

Further, pieces of evidence from an evidence set are randomized (i.e., shuffled) and distributed to the pairs. Students have to move around the classroom to find the student-pairs that have the two pieces of evidence that support the claim on their argument builder, while other student-pairs are hunting down the evidence that they were “dealt” in the effort to complete argument builders.

Further, pieces of evidence from an evidence set are randomized (i.e., shuffled) and distributed to the pairs. Students have to move around the classroom to find the student-pairs that have the two pieces of evidence that support the claim on their argument builder, while other student-pairs are hunting down the evidence that they were “dealt” in the effort to complete argument builders.

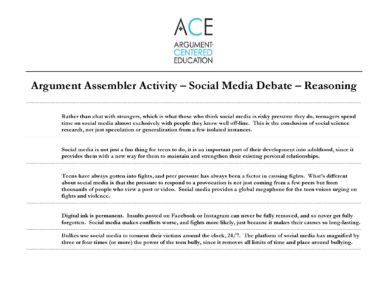

Reasoning and the Argument Assembler Form

In most versions of the Argument Assembler Activity, student pairs must create their own reasoning, to analyze the ways that the evidence proves that the claim is true. Because this version was scaffolded up, however, we also prepared the reasoning for each piece of evidence and similarly randomized and distributed them.

Students use the Argument Assembler Form to collect the strips of evidence and reasoning that develop and substantiate the argumentative claim that they were assigned.

Students use the Argument Assembler Form to collect the strips of evidence and reasoning that develop and substantiate the argumentative claim that they were assigned.

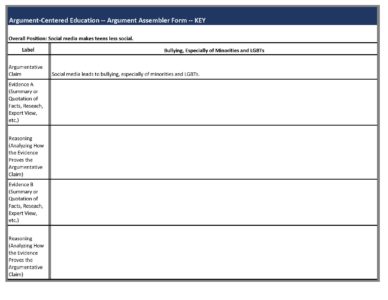

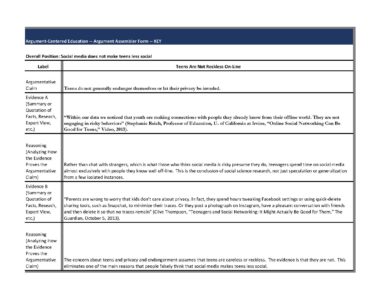

The final and finished ten arguments (five on each side) should look like they do in this Argument Assembler Form “answer key.”

The final and finished ten arguments (five on each side) should look like they do in this Argument Assembler Form “answer key.”

Moving to the Large Group Debate

Moving to the Large Group Debate

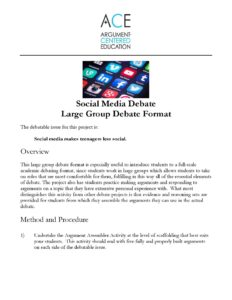

With arguments fully assembled and in place, it’s time to move to conducting the large group debate that culminates the project.

This large group debate format is especially useful to introduce students to a full-scale academic debating format, since students work in large groups which allows students to take on roles that are most comfortable for them, fulfilling in this way all of the essential elements of debate. The project also has students practice making arguments and responding to arguments on a topic that they have extensive personal experience with. What most distinguishes this activity from other debate projects is that evidence and reasoning sets are provided for students from which they assemble the arguments they can use in the actual debate.

A downloadable version of the Large Group Debate project description and format is here, though we’ll hit most of the steps in the remainder of this post:

Assign Positions

Assign Positions

Up until now students have been researching and even assembling arguments without knowing what their position in the culminating debate project would be. Now those positions should be assigned. But first the class had to be divided in half, and then each half was divided again, so that the class was broken out into four large groups. A group leader was identified from each group. Then, randomly (though it could have been done by canvassing student preference), students were assigned to a side (i.e., position) on the debatable issue.

Counter-Argument Building

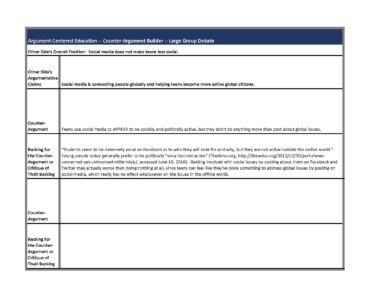

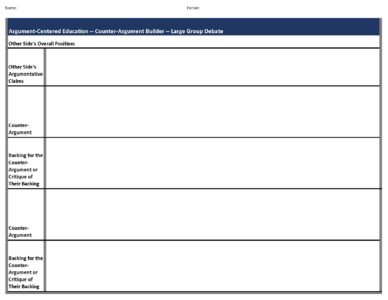

Each group received copies of the Large Group Debate Counter-Argument Builder.

Group leaders facilitated a discussion within their group about the arguments built in the Argument Assembler Activity. Though no groups did that in this implementation, any group could have determined that it wanted to build an additional argument. The main purpose of this discussion was to rank the arguments from 1 to 5, with one being the argument they wanted to make most in the debate.

Group leaders facilitated a discussion within their group about the arguments built in the Argument Assembler Activity. Though no groups did that in this implementation, any group could have determined that it wanted to build an additional argument. The main purpose of this discussion was to rank the arguments from 1 to 5, with one being the argument they wanted to make most in the debate.

The teacher then models counter-argument building, using the models provided with the resources in this project.

Modeling should highlight the difference between critical counter-arguments (arguments that critique other arguments’ evidence and reasoning) and independent counter-arguments (new arguments with their own evidence and reasoning).

Group leaders assigned each student an argument from the other side of the issue (one of the five arguments built in the Argument Assembler Activity) to build counter-arguments against. These counter-arguments should either critique the evidence and reasoning of the argument (i.e., a “critical counter-argument”), or it should put forward its own evidence and reasoning (i.e., an “independent counter-argument”). The Counter-Argument Builder asks students to construct two counter-arguments for each argument that the other side might make.

The Large Group Debate Format

When students were given (in this case) about a period and a half, adequate time to prepare their arguments and (especially) their counter-arguments, the large group debate should begin. A student from one group for the affirmative side stands and presents their best argument. Then a student from the other affirmative group should presents their best argument, as long as it isn’t the same argument as the first group.

The same process takes place with the two groups on the negative side.

The teacher is tracking these arguments on a white board, in different-colored markers, or on an electronic flow sheet on a projector, with different colored fonts. All of the arguments in the large group debate should be flowed by the teacher.

There is then a 5-minute break after the arguments from both sides are presented, during which all four groups should be refining and making final determinations about their counter-arguments. The first groups from both sides are matched for the purposes of counter-argumentation; and the second groups from both sides should be matched.

Counter-argumentation begins with the negative groups. The first group offers one or two counter-arguments to the first argument made by the affirmative side. The second group does the same against the second affirmative argument. Then the affirmative groups replicate that same process against the two arguments that the negative groups presented. Note that the affirmative does not respond to the negative counter-arguments, but instead makes counter-arguments against the negative’s opening two arguments. The counter-argument speaker in each group should not be the same student who presented the opening argument.

Another 5-minute break takes place during which each group prepares final argumentation, called “argument evaluation,” formally. One negative group offers its argument evaluation, then an affirmative group, then the other negative group, and finally the last remaining group on the affirmative side.

LARGE GROUP DEBATE FORMAT

Affirmative Arguments 4 Minutes

1st Group

2nd Group

Negative Arguments 4 Minutes

1st Group

2nd Group

Preparation Period 5 Minutes

Negative Counter-Arguments 4 Minutes

1st Group (Responds to 1st Aff Group)

2nd Group (Responds to 2nd Aff Group)

Affirmative Counter-Arguments 4 Minutes

1st Group (Responds to 1st Neg Group)

2nd Group (Responds to 2nd Neg Group)

Preparation Period 5 Minutes

Argument Evaluation 6 Minutes

1st Negative Group

1st Affirmative Group

2nd Negative Group

2nd Affirmative Group

Feedback and Assessment

The teacher then provide feedback, pointing to the argument tracking that she has been doing, and/or more formal formative assessment. She can also announce a winner of the debate, with rationale.