School Choice — An Argument-Centered Approach

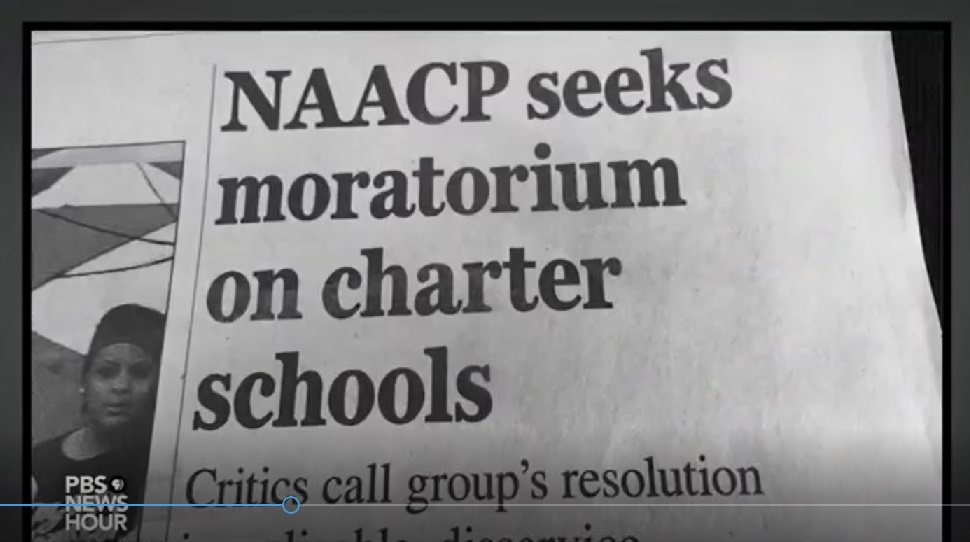

In the education sector, the biggest hot button policy issue today is probably school choice. Charter schools, which are publicly funded and privately owned and managed schools; and tuition tax credits and vouchers to fund students attending private schools — these policy disruptions of the school district operated and managed status quo in public education have generated an enormous amount of discussion and debate. And this has taken place at every level, from the local community town hall (and even in family conversations) up through state legislatures and boards of education, to the U.S. Department of Education and the halls of Congress.

This is the final post in a short series that reflect work that we have done this summer to prepare argument-based units on issues of particularly strong interest to secondary and middle school history and English departments, going into the 2017/18 school year. This post develops a unit on school choice, and whether in particular charter schools are disrupting the traditional public education system in the United States in a positive or a negative way — or perhaps (looking toward a syncretic position post-debate) in what specific ways they can help public education and in what specific ways they threaten it.

Overview

There are now nearly 7,000 charter schools in the United States, serving about 3 million K-12 students. More than 6% of the K-12 student population attends a charter school, a four-fold increase over the past 16 years. Charter school expansion accelerated in the Obama years and, in naming devoted school-choice advocate (and billionaire) Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education, the trend toward charters and choice will likely heighten under the current federal and state governmental leaders.

Charter schools – which are publicly funded and privately owned and managed, often by non-profit organizations but sometimes by for-profit companies – were the idea originally of teacher-leaders who wished to create “laboratory schools,” able to innovate and adopt new strategies outside the regulatory control of school districts. About twenty years ago, however, charters began to be pushed heavily by both education reform groups with a significant ideological commitment to free-market solutions and entrepreneurship, and by private-sector companies interested in the prospect of applying their business motives (including the pursuit of profits) to the public education sector. Most teachers – and all teachers’ unions – now are either skeptical of or hostile to charter schools and the school choice movement.

The key question for our society – even more so for current middle and high school students and their parents – is whether charter schools and school choice more generally are improving American education or not. Both sides clash over data – whether it proves that charter school students do better or not on standardized tests than their neighborhood school counterparts (or relative to the schools in their city or state overall), and what it says about the impact that introducing school choice has on “traditional” (the school choice movement’s preferred term) public schools (whether competition helps or hurts these non-charter, “regular,” district-run schools). More advanced study of this debate requires that students dig into the data, to look at its methodology, assess its credibility, and attempt to judge its applicability. Beyond the data, school choice advocates suggest that the incentives to improve that introducing choice imposes always improve the providers of a service or product, in any industry. It is just logical: when providers have to compete for the same “business,” they try to out-compete each other. Opponents of school choice and charters decry the direction in which charters point: toward privatizing public education. They argue that neighborhood public schools have always been a critical component of our democracy.

The debate over charters and school choice has come into focus for the American public. And it promises only to heat up over the coming months and years, with profound and far-reaching consequences for this current generation of young people, their parents, the education profession as a whole, and American democracy itself.

Debatable Issue

Does school choice improve public education?

Sources

The textual and visual media sources for use in this unit are combined into our Media List.

To make it easier for our partner schools to access and screen crucial video documentary shorts, we have downloaded them and embedded them here, in the same order as the appear in the Media List.

Videos that present background on the school issue, or offer information and testimony for both sides of the debate, come first.

The next set of videos support school choice and have evidence and information to help students build arguments in favor of charter schools.

And this set of videos below opposes school choice and has evidence and information useful to students in building arguments against vouchers.

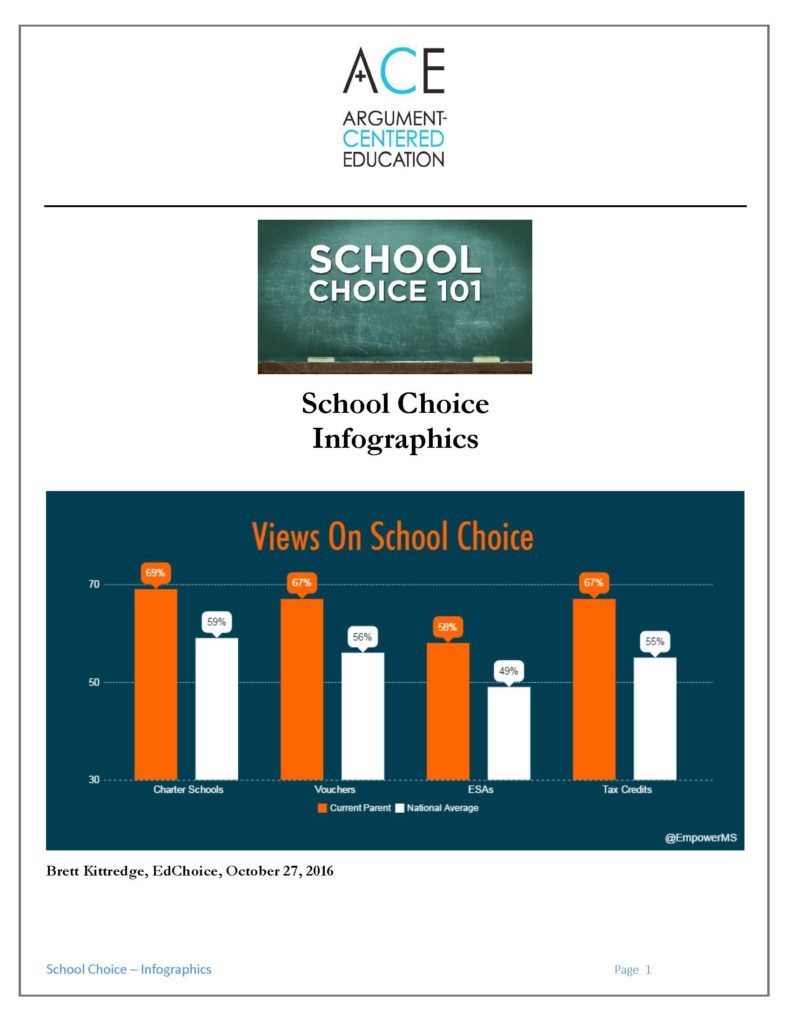

Selected Passages and Infographics

We incorporate the use of Selected Passages and Selected Infographics documents to scaffold students’ evidence selection and research skills. We use them more extensively with students less experienced with academic argumentation, and less extensively with students more experienced.

Here are the Selected Passages and Selected Infographics documents for the school choice argument-centered unit.

Claims and Counter-Claims

Another scaffolding method and teacher resource we incorporate (as an instructional option) are sets of possible claims and possible counter-claims. These have a wide variety of uses: they can be distributed to sides in a Refutation Two-Chance activity, to facilitate getting to the refutation stage of the game; they can set up an Close Evaluation of Arguments activity; or they can help students get started in their argument building or argument writing.

It is always a solid foundational strategy for teachers to walk into an argument-centered unit — on any content they are teaching — with a set of claims and counter-claims that students can make and support on the issue. Having these sets of possible arguments and counter-arguments ensures that the issue as you have framed it is balanced and focused enough to generate viable claims on both sides. To produce these sets you also need to have at least mentally scanned through the content resources and identified evidence that students can find and use to support these arguments. And finally these sets help guide your organization of content instruction around argument. They are, in short, vital argument-based instructional resources.

Applications

As with other argument-centered units, there are a good number of argument-centered applications that can be used to engage students in the academic work students should be asked to do to activate and demonstrate their learning about school choice.

Argument Essay

Students can simply be required to write an extended argument essay that requires them to put together their ideas and weigh in on the issue of school choice.

Carefully read and annotate the attached set of secondary-source document excerpts. Use information from at least four of the sources in a coherent, well-developed essay that has an introduction, argumentative body, and conclusion. Your essay should take a clear position, stated in a thesis, on the issue. Your thesis should be supported and developed by 2 – 3 arguments. Each argument should have a claim, evidence, and reasoning, using one or two pieces of evidence from the set of sources. You should also address and refute at least one counter-argument, either in a separate paragraph or in your argument paragraphs.

Use the set of sources to identify evidence that will support your claims, and supply your own reasoning to explain how it is that each piece of evidence proves that your claim and your overall position are true. Avoid merely summarizing sources. Indicate clearly which sources you are drawing from, whether through direct quotation or paraphrase.

Other Argument-Based Activities and Projects

Lucy Calkins and her colleagues, in her 2013 book The Research-Based Argument Essay, affirmed the value of conducting oral argumentation and debates in class prior to writing.

We’ve come to believe that it would be advantageous to students if we found opportunities throughout the day to immerse them in a culture of debate, or argumentation (in the best sense of the word). And we believe that it would invigorate the school day to find many opportunities, often, for students to take and defend positions, to learn from argument and counterargument. The research is clear that if students have opportunities to do the work orally that we hope they will learn to do as writers, this is advantageous to them.

These activities and projects can substantially improve and deepen students’ organization, critical thinking, use of evidence, and effectiveness in engaging with the other views and ideas on the issue. Or they can stand on their own as a summative assessment or unit project on the issue of school choice.

Templatized Argument WritingSchoolChoiceWritingAssessment17.08.03