The Issue of Free Public College and an Argument Writing Assessment

Overview of the Issue

One of Abraham Lincoln’s great achievements as President was to found in 1861 land grant colleges, which evolved into the nation’s four-year public colleges and universities. A college education at a public university has been a ticket into the middle class and upward mobility and opportunity for millions of people. For about 100 years – and most especially after World War II and the passage of the GI Bill – the cost of going to a public college or university was minimal or free. However, over the past 30 years, tuition at these institutions of higher learning has been climbing steadily. Today, the average tuition at four-year public college is nearly $20,000 per year. With room and board, the cost has climbed to more than $40,000 annually.

What was once free or nearly free has become unaffordable to the majority of young people in the U.S. Hit especially hard have been groups under-represented in positions of power and success in our country: African-Americans, low-income people, first-generation college students. College is increasingly becoming a means of social stratification: making the wealthy wealthier, and the pushing the poor farther and farther away from opportunity. To try to deal with the costs, many students have taken out substantial loans, and student loan debt has become its own potential problem, exceeding $1 trillion in total, more than the nation’s combined credit card debt.

The public has become concerned and is putting pressure on government to react. In the 2016 presidential election, college affordability was an issue, especially in the Democratic primary. Senator Bernie Sanders had as part of his campaign platform making public college free, by massively increasing federal subsidies to state colleges and universities. Other candidates, including Hillary Clinton, did not support free college, but did offer positions and arguments of their own to try to address the issue.

Free public college is supported by its advocates because it offers opportunity to those who cannot afford college now, and is, they say, a fair and proper extension of K-12 public education. Opponents make a number of arguments, including: cost is less important than academic readiness and interest as a reason students do not get a college degree; low-income students already have access to aid, so free college really only helps middle- and upper-income families; and free college would mean a less efficient, innovative, and selective university system, lowering the quality of a college education. This debate is vital, vibrant, important, and on-going, and through the use of this argument writing assessment, students can weigh in on it with their own evidence-based arguments.

The Debatable Issue

Should public college in the United States be free?

Argument Boxing as Pre-Writing Preparation

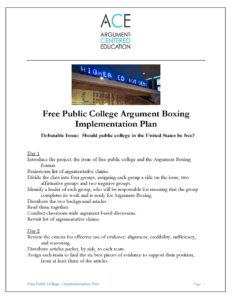

Some teachers prefer to conduct an argument-based activity in the lead-up to and preparation for an on-demand argument writing assessment on this issue. One excellent activity for this purpose is Argument-Centered Education’s Argument Boxing. This pre-writing work should be built around an Implementation Plan. This one is for five days of instruction and argument preparation work:

The Argument Boxing format is usable with any debatable issue. The key to its successful implementation is based in three elements.

- The teacher has to carefully track argumentation on the white board or smart board in a way that all students can see and that tracks only new, advancing argumentation and that follows all of the argumentative engagement and refutation.

- All students should be required to participate in argumentation made during the Argument Boxing activity itself. This can be enforced using chips or figurines — two per student — and a rule that states that no one can speak a third time until all students have used their second figurine or chip.

- Students need to have prepared and built arguments and counter-arguments in advance of Argument Boxing.

Argument Writing Assessment

If the argument writing assessment is on-demand — and we recommend that teachers intersperse longer argument writing projects with on-demand, single-period writing assessments — students should be told to carefully read and annotate this set of secondary-source document excerpts.

Students should be required to use information from at least four of the sources in a coherent, well-developed essay that has an introduction, argumentative body, and conclusion. Their essay should take a clear position, stated in a thesis, on the issue. The thesis should be supported and developed by 2 – 3 arguments. Each argument should have a claim, evidence, and reasoning, using one or two pieces of evidence from the set of sources. They should also address and refute at least one counter-argument, either in a separate paragraph or in your argument paragraphs.

Students should be told to use the set of sources to identify evidence that will support their claims, and supply their own reasoning to explain how it is that each piece of evidence proves their claim, and their overall position. They should avoid merely summarizing sources. Students should indicate clearly which sources they are drawing from, whether through direct quotation or paraphrase. They should cite sources either by their letter (A – J) or (even better) by their author, emphasizing qualifications where appropriate.

If working with a longer argument writing project, students should develop at least three arguments to support their thesis. They should include refutation of a counter-argument with each argument they make. And they should research from a Media List on the issue.

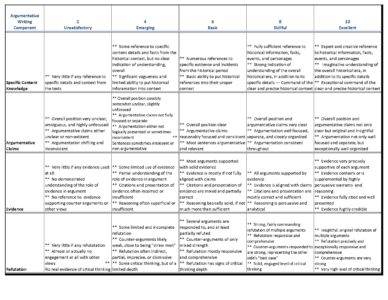

Argument Writing Assessment Rubric and Form

We recommend using the Argument-Centered Education assessment rubric and form, and providing detailed feedback on student writing as promptly as possible. If the project is longer-term, this rubric and form can be used on the drafts, enabling students to revise in response to your feedback before turning in the final writing product.