A Teacher-Designed Evidence Catcher, Accenting Citations

Otis Middle School (Chicago) social studies teacher Elizabeth Valente has adaptively re-designed our resources into what she calls an Evidence Catcher for the project we have been working together on in her argument-centered ancient Greece unit this semester. The resource represents another exemplar of our goal that teachers at our partner schools acquire the capacity to design and deploy their own argumentalized and critical thinking enriched curricular resources. Ms. Valente has agreed to share this resource, at which it is well worth taking a closer look.

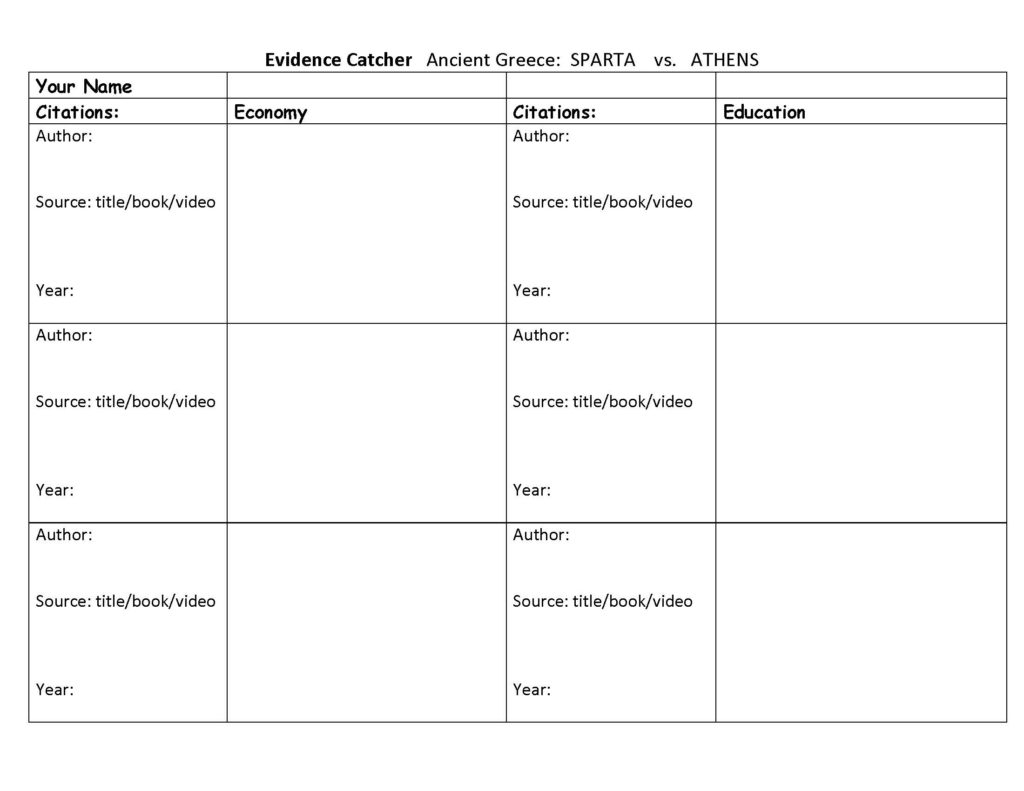

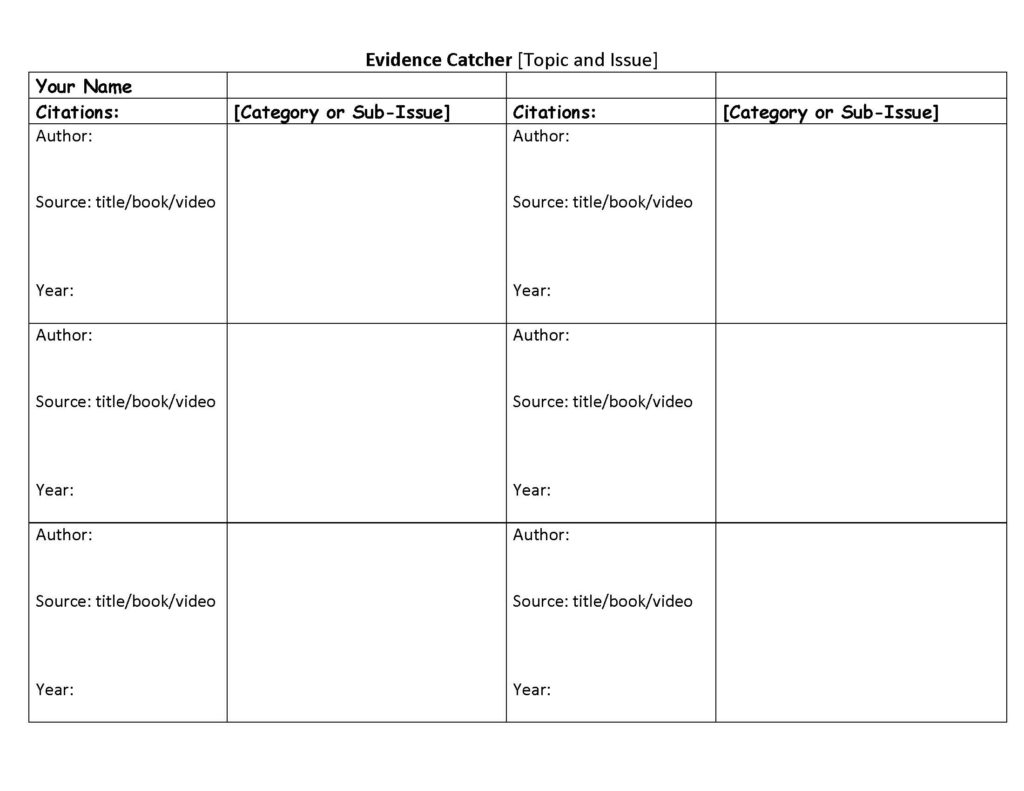

The primary purpose of the Evidence Catcher is essentially the same as that of other evidence collectors and identifiers: to give students a place to upload, maintain, and track the information, facts, quotes, examples, data. This is the raw textual material from which they will draw to supply their arguments with evidence. There are several features in the Evidence Catcher on ancient Greece that are worth noting.

Citations are accented

Ms. Valente has been concerned that her students have not been citing their evidence properly, if at all, during their classroom debates, structured argumentation activities, and argument writing assessments. In the Evidence Catcher students are required to provide a complete citation next to every piece of evidence that they input.

Entries are organized by category or sub-issue

The argumentalized project on ancient Greece is organized around five domains around which city-states then, and societies since, are organized: economy, education, government, military, and the treatment of “minorities” (in this project, women and slaves). The Evidence Catcher is organized the same way, around these five categories of evidence. These categories are, in effect, sub-issues, on the unit’s debatable question:

Which city-state, Athens or Sparta, presents us today with the better model for organizing a society?

Students are able to formulate their claims (the reasons for their position) in line with these categories.

Multiple Evidence Catchers are in play

In the basic version of the Evidence Catcher on ancient Greece, students have chosen or been assigned their position, and they are searching for the best three pieces of evidence for each category (economy, education, etc.) that they can find. (Note, though, that there is a sixth category, “Other,” on the third page of the Catcher, for use when a student finds more than three potentially usable pieces of evidence on a sub-issue. Students should put the sub-issue for this “other” evidence in parenthesis.)

But Ms. Valente didn’t want to deploy the most basic version of her resource. So she has had each student complete a separate Evidence Catcher for each position, before they have gotten the side that they will take in the classroom debates. Also, she has given students the opportunity to use more than one Evidence Catcher for each position, dividing the sources into video/venn diagrams for one Catcher, and documents and textbook evidence for another.

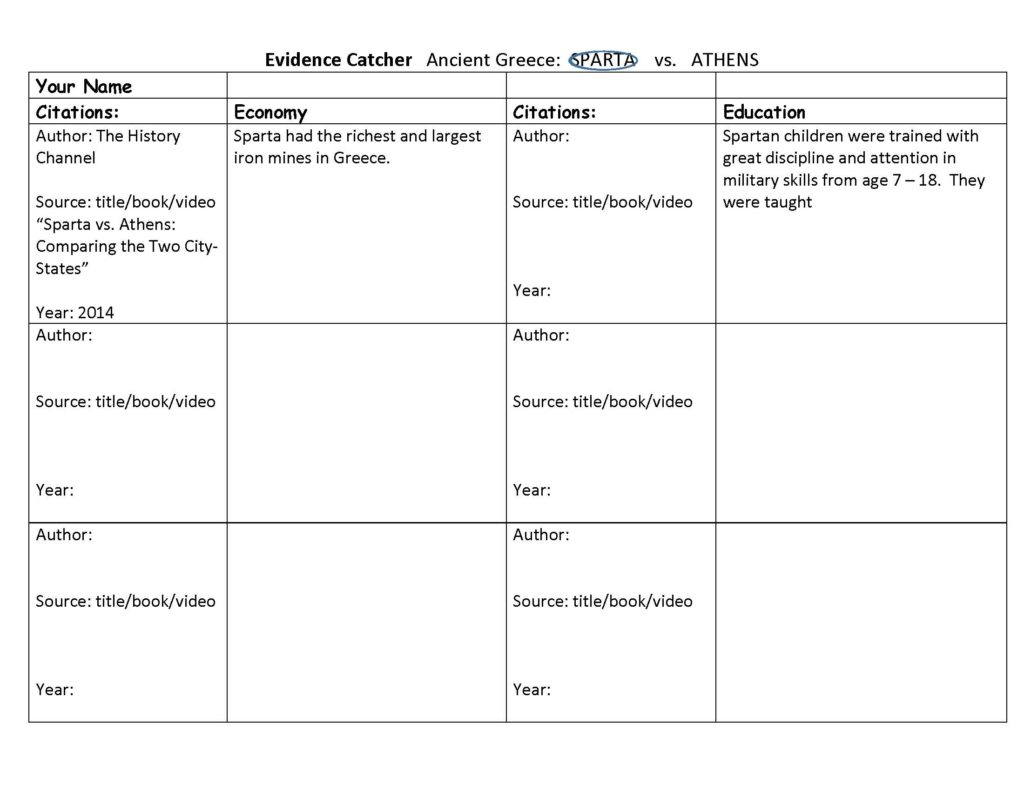

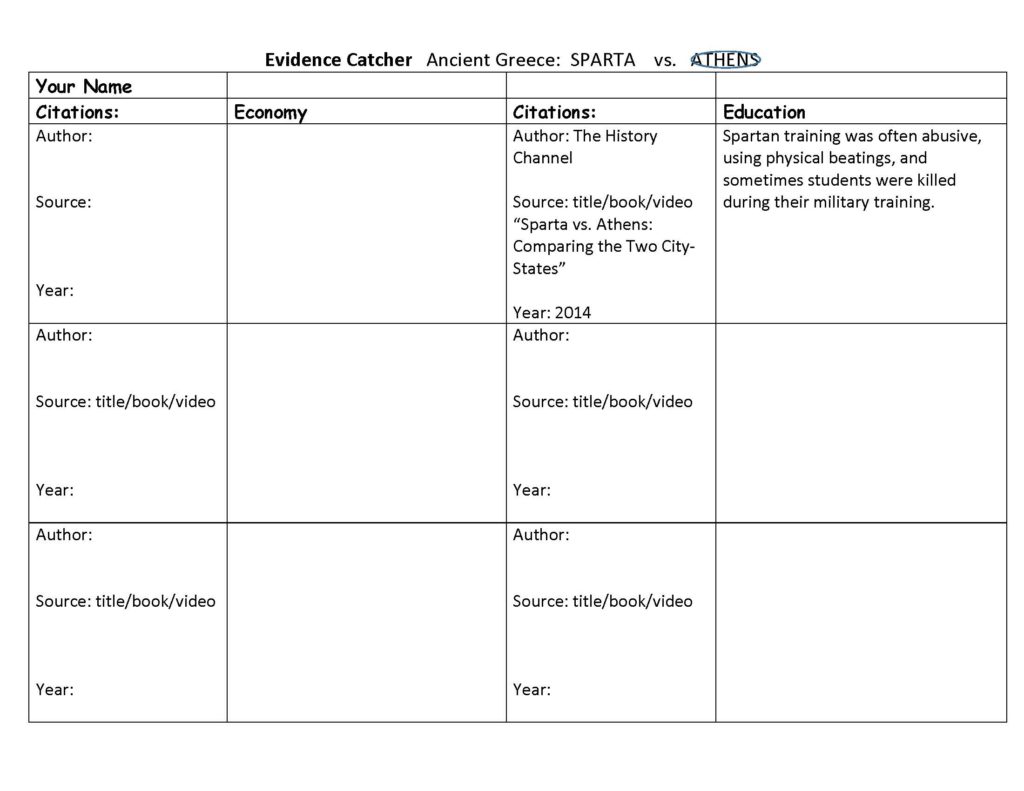

We have provided students with portions of the models we developed for use of the Evidence Catcher on ancient Greece when viewing the central documentary video for the project, The History Channel’s “Sparta vs. Athens: Comparing the Two City-States” (2014).

We made several observations before presenting a portion of these models to students.

Evidence entries should either be facts or authoritative conclusions

Evidence, no matter the discipline or the specific argumentative context, should always aspire to be factual. We say “aspire to be” because what the facts are — in this case, of history — are themselves subject to argumentation and debate. This does not mean that people are entitled to their own facts or to manufacture facticity, but it does mean that often we can have productive differences about what the facts actually are; through these disputes we are likelier to come to the truth, since both side’s understanding of the facts is tested by the other’s. Students will find it challenging to cull from a source that aspires to be factual, but through practicing the process students learn to reliably distinguish facticity.

Videos lend themselves to paraphrase or summary more than quotation

It is a truism commonly repeated by us that there are only two things you can do to process text into evidence: quote or paraphrase (when you condense a paraphrase you summarize). If you think about it, there is no other way to extract evidence from a text — in writing, video, image, sound, anything we agree to call a text. Videos move rapidly, in images and in the spoken word, so most of the time students will need to paraphrase (or summarize) what they hear and see in a video to upload it into the Evidence Catcher. Catching becomes more difficult to do. We recommend two aids here. One, always play important videos twice. Repetition is essential throughout education, and nowhere more than in using videos as instructional tools. Two, push pause on occasion to flag and explicate portions of the video that are especially salient — without over-doing it and undercutting the momentum and narrative and analytical flow of the video.

We have distilled the Evidence Catcher into a universal version, usable in any argument-centered project.

This resource is in Word, so that it is easy to edit and adapt.

Let us know how you are able to edit and adapt this resource for your academic argument work in your classrooms — info@argumentcenterededucation.com.